Note: Update: Robert gets closer to Lena’s secret …

You can start reading here or anywhere, then go back. See Table of Contents. Come in the middle? Robert is the narrator who discovers after his wife Lena has died that she had a lover, Isaac. Evan is Isaac’s wife. Robert is on a search for how he lost Lena: He’s creating the story through memory, invention and a search for the truth and his role in what happened—and by stalking Isaac.

Losing Her

She was like her beloved Qumrum caves. From those caves, I’ve learned since I’ve seen the Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit, a history was reconstructed. Because she was sick, because she didn’t recover, because she was prescient about this fact, the reason I now think she rented the room in Gershon’s house, she gave up secrets cryptically.

I suspect this is the way archaeological finds reveal: a fragment here of rock, the wadi that unfolds below that tells tales about a cistern, that leads to a water system and a potter’s kiln that fired the clay jars where the parchment was found, a cemetery.

I sought narrative and chronology and she sought consciousness, a search that cared little for either.

She began, “I remember the narrow path to the three steps—the stoop, the cement porch with the metal chair and the glider and the narrow front door and the blue living room with the Queen Anne chair.” Her childhood home.

“The front door was white with a small window at the top and the door opened into a narrow blue living room with the lady’s high-backed chair, quilted and embroidered with blue stitching. My mother always sat in that chair. My father sat in the soft square blue, suede chair with a large loose pillow in the bottom. The house smelled like sweetness, sugar, butter and apples steaming on the stove. In the pot, apples my mother had taken out of the Caloric refrigerator. The milk in the refrigerator was Sealtest in a bottle and next to that the chocolate milk in little individual bottles, a treat for me. Slow cooked beef, round steak that she’d seared, then braised. I remember Kitchen Bouquet, Worcestershire sauce, ketchup on the porcelain drainboard. Left over meat from last night’s dinner sat in a glass casserole covered with tin foil. Earthy, onion-smelling beef that fell apart when you touched it.”

“Are you hungry?”

“No. She put a sunny side up egg on my plate every morning before I went to school. She told me I needed it ‘to hold you after lunch’—that’s the way she put it. But I had trouble getting down the glassy yellow eye that looked up at me from the plate. I regret that. Because now I think that phrase. Do you know what I mean? I say it in my head.”

“Which one?”

“To hold you.”

“You miss her.”

“Yes.”

“You were their love child.”

“Why say that? Say it that way?”

“Why ask?” I said.

“Because that means out-of-wedlock.”

“I meant you came from love.”

“And we didn’t have children.”

“I don’t think I would have been a good father. I would have been critical, harsh like my father. I’m not sorry we didn’t, that we couldn’t. What about you?”

“What about me?” She took the baby pillow out from under her side and held it.

“Children? I know you couldn’t, but did it matter?”

“Why haven’t you ever asked me why I couldn’t?”

“Because I know why. What are you saying?” Not fertile. That’s a reason. It happens. I didn’t want children. I wanted her.

“I’m fucked up.”

“Because you couldn’t have children?”

“Yes.”

“You were circumstantially challenged.”

She laughed. “Yeah, you could say that.”

“Is this something we need to talk about?”

“Probably not.” She was holding the baby pillow against her chest, her wound.

I asked, “So when Evan came—When did Evan come?”

“I think we’re friends or something like that.”

“You don’t know?”

“I think she understands that sometimes things aren’t logical.”

“You mean that I insist on logic.”

“I didn’t say that. She has children. She knew it would help. You know, the baby pillow.”

“You haven’t answered my question.”

“What question?”

There were too many questions because she lay in this room in this house—not our house, not our room, not even the room off the master bedroom.

Then she said, “We played Trivial Pursuit in the later years.” She was talking about her mother and father, family dinners with her uncle Abe and his wife Martha before he died, the brother her mother lost out of order, her younger brother. “Remember that?”

“Yes, of course.”

“She answered whenever she knew even when we put her on a team with Abe, who knew stuff.”

“He’d yell, ‘You’re not on their team.’ ” And we’d all laugh at her mother’s child-like way. I know the answer, I’ve got to tell.

“She’d say, ‘But Carole Lombard was the one who crashed,’ as if that explained why she’d answered.” The question was something about a famous actress who died in a plane crash. Lena sat up in bed and said to me with mock sternness, “You know that Clark Gable never got over losing her.”

“She said that.”

“You remember,” Lena said.

A few months ago I was called to jury duty, my first time in D.C. In the District, I’ve since learned, the calls to jury duty come much more frequently than they did in Virginia and I’d wanted to serve. Sure, I thought it was my civic duty but also the thought of sitting in judgment appealed to me, to my certainty about who I was and what I believed. I’d only been called twice in all the years we lived there—our whole married life until she rented the room—but something about my demeanor, I suppose, caused me to be rejected both times. But this time, after I’d moved into the District, after I’d sold the house in Virginia because there was nothing there for me after Lena died, I was taken. The case was some ridiculous suit: A man and his girlfriend sued the woman who hit them when she went through a red light on Constitution Avenue at 17th Street. She was going less than fifteen miles an hour, we were told, based on the nature of impact to the couple’s car, barely a dent, but they were suing her for damages—medical bills, lost work pay. They wanted her to pay.

The judge said, “You alone determine the weight, the effect and the value of the evidence, and the believability of the witness.” I wrote down what she said. “The term ‘preponderance of the evidence’ does not mean that the proof must produce absolute or mathematical certainty. For example, it does not mean proof beyond a reasonable doubt as required in criminal cases.” She continued, “Circumstantial evidence is indirect evidence of a fact which is established or logically inferred from a chain of other facts or circumstances. For example, direct evidence of whether an animal was running in the snow might be the testimony of a person who actually saw the animal in the snow. Circumstantial evidence might be the testimony of a person who saw the tracks of the animal in the snow, rather than the animal itself. You may consider both types of evidence equally.”

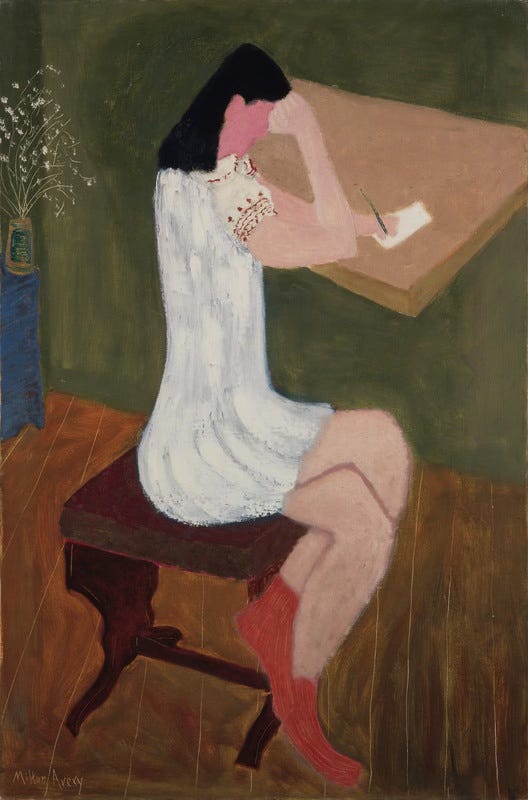

I go to the Phillips regularly now. I study perspective. Recently, I stood before Milton Avery’s Girl Writing.

The floor and the desk slide forward like the checker players in the Matisse print that used to hang in our house. The girl wears a white dress, red embroidery on her sleeve. She wears red socks. Along the wall is a white airy flower in a jar in the corner. But the paint is thicker on the flowers than on the girl. The flowers, the background, come forward. The artist is quoted on the wall, “I do not use linear perspective, but achieve depth by color—the function of one color with another. I strip the design to essentials; the facts do not interest me as much as the essence of nature.”

I took that advice while I considered the evidence. ▵

Table of Contents

Coming next: “Her Story’ Chapter 29

Only Connect, all sections, and this serial novel come from my heart and soul—and ten years of research. I know the saying ‘time is money,’ but I couldn’t help but pursue this story. If you have already gone paid, my heart goes out to you with my thanks.

Love,

Your perception of the nature of we humble beings is deepened with every chapter dear Mary, your melange of story and fact profoundly beautiful. Roberts digging deep for meaning, reassembling facts; this is what we do, even when answers will never be laid out in exactly the way we wish... ❣️

Wonderful I loved the opening conceit of Lena as the Qumrum caves, giving up her secrets archaeologically. And the closing passage about evidence and Matisse's search for the essence of things. Beautifully blended with the story