She often spoke in metaphors that intrigued me: When the mind’s free, the body’s delicate. That was the sort of thing she’d say and then add, Lear, you know. But I didn’t know. She was my literature, my storehouse of narratives.

I said, “What do you mean?”

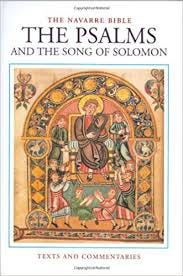

“Do you want children?” She reached for her purse. I thought she might leave. Instead, she emptied her purse onto the floor, looking for a tissue. A notebook with Post-It notes all over it for, as I already knew, deposits or withdrawals that would need to be tallied at some point in her checkbook that she kept at home, a lipstick, a pouch of some sort, her wallet with the money squished in the disorder of ones with twenties or fives and a slim book, The Song of Songs.

She was often dropping things. She was clumsy, disorganized with a child-like charm. She was thin as a reed. She was a woman who carried the music of the Bible in her purse.

I scrambled for the tissue on the floor to dry her tears. With that awkward move, I knew I was her answer.

I was forty and long past wanting the encumbrance of children, thought I’d never marry until I met her. I said, “I want you. You and me. We’ll be enough. Why would I want any more than you? You with your umbrellas popping, your books, your purse and all that stuff that falls out.”

And so we married.

But I was like a cold burn.

In Whiting, when I was a child, the house across the street blew up in a silent explosion while I slept. Bake, who lived there with his wife and children, had gone down to the basement before five in the morning because the house was cold. Our guess is he lit a match to light the boiler and the air exploded around him, throwing him onto the floor with a head injury that would kill him while his wife and children ran from the house before its walls fell in on themselves. The firemen came to put out a fire that hadn’t occurred and I woke to the single siren of the town’s one fire truck. This explosion that made no sound any of us heard—who knows what Bake heard before he fell?—was a cold burn, how I think of it.

I’ve turned the CD player off; shut down Emanuel Ax with his force, deprived myself of the strings, of the sweet: Rebecca Young’s viola, Yo Yo Ma’s cello, Edgar Meyer’s bass.

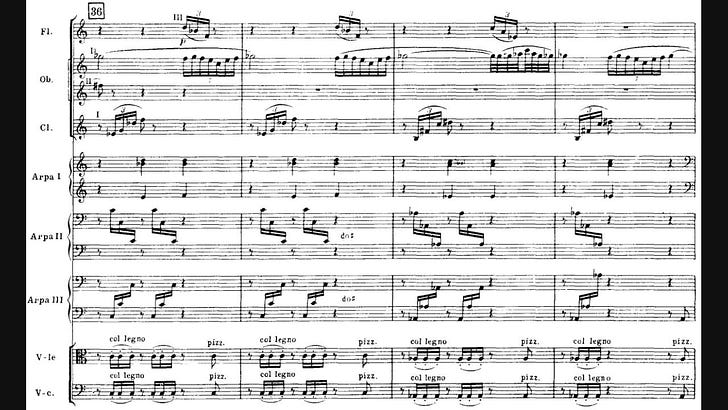

I open the score of Stravinsky’s The Firebird, let the horns dominate the strings in the movement “The Infernal Dance Of King Katscheï,” recall the siren that woke me that morning when I was a child and think how Lena waited for me. She hoped I’d break through and come to her, burst on her with desire from joy, from playing the piano, where she saw that could happen.

She must have believed that’s what she got from Isaac. Isaac, her lover.

I don’t know what he felt for her though I try—he remains difficult for me. But I’ve begun to know what she felt for him because I understand what she couldn’t get from me.

I’ve hated him, tried to imagine that I was the cool center between them—the space that kept them apart.

I’ve tried to hate her.

Wonderful, evocative, interestingly whimsically beautiful.