Welcome guest post—and subscribe—by Michael Mohr, who tells us how literature, the key books he’s read have affected his life, career, and well-being. I’ll comment in key places.

Dead White Men,

I’ve always been a voracious reader. Growing up in Ojai, 90 miles northeast of Los Angeles, I became fascinated with my author-mother’s impressive library. My mom—writer Lori Windsor Mohr—had for years read the classics to me. I can still remember sitting in the darkness of the living room, sitting across from her on a little white couch, the only light a tiny halo against the pages of whatever book she read. I got sucked into the worlds of John Steinbeck, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Earnest Hemingway, Flannery O’ Connor, Boris Pasternak.

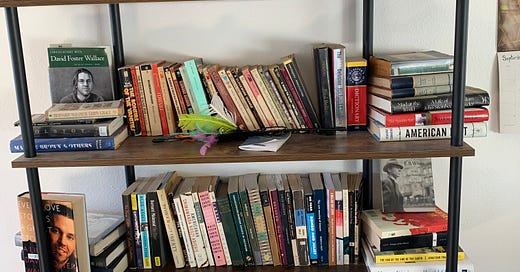

When she wasn’t reading to me at night, pulling me into foreign worlds, I’d pick out books from her library. I loved not only the words and the sentences on the pages, but the smell of the old, dusty tomes lined up like little soldiers one by one along the old wooden shelves. Sometimes I’d pick up a random book, open it, close my eyes, and take in that ancient, reverent stink. I still cherish that smell to this day. I can’t exactly explain why.

As a kid I was both social and loved going outside and yet also, at other times, interested in only one thing: Reading. In the early-mid nineties I’d often spend a whole weekend devouring The Redwall Series, by Brian Jacques, a fantasy series about a kingdom of mice. And of course there was Lord of the Rings.

Mary: I love this from Hèléne Cixous:

As a child, when my mother and I got into harsh fights—which became more and more frequent as I leaned towards my teenage years—we’d scream, yell, throw our hands up in the air, and mutually slam our doors. But, inevitably, an hour later my mom would slide several sheets of paper under my door: A written statement trying to bridge the gap between us, seeking consolation and pardon. I would reciprocate, sometimes writing several pages, and slide that under her door. Eventually, we’d open our doors, hug, and “start over.” It was a beautiful, tender tradition, and one we still in many ways adhere to even now.

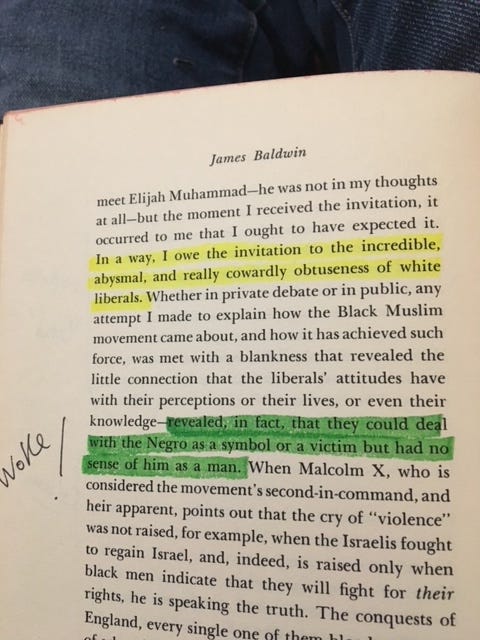

In my wild, anarchic teens I lost sight of reading. Punk rock, drinking, constant shows, rebellion and girls took over. In my early twenties, living in San Diego, I read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road which shattered all the bourgeois ideals I had left inside me (not many by then). I decided I had to do THAT. Literally. So, for five years, on and off, I moved constantly, hitchhiked across and all over these rugged United States, hopped freight trains, and lived “off the grid,” as they say. During all these years, I read. I always had a bent, torn, dog-eared paperback in my stinky traveling bag. It was essential. I read the Beats but also Charles Bukowski, Susan Sontag, James Baldwin, Norman Mailer (in all his sexist glory), Dave Eggers, Ta-Nehisi Coates. I was, slowly, absorbing the 20th and early twenty-first-century masters. I was becoming a writer.

Writers, as they say, are simply talented, ambitious readers. I kept thinking, I can do something like this. I knew I wasn’t the next Sontag or Mailer or Kerouac but I felt I was destined to write.

At 29, I had my first short story published. I started writing a novel. I got a degree in writing. I interned for a literary agent. Writing conferences became the norm. My literary life took off.

*

In my thirties reading really sunk its hook deep inside me. I lived in San Diego, Santa Cruz, San Francisco, Oakland, Portland, and then New York City. Through all of this I read. Reading felt safe to me, a tradition I’d known since childhood. You could have a private conversation with authors long dead. These authors seemed to beckon to me from the grave, to highlight the fact that, weirdo/freak/sensitive/artist person that I was, I was not alone. Others had come before me. Others had seen the world through a similar self-aware, hypersensitive lens, and had written their thoughts down. I felt like I belonged to an ancient tradition, leading all the way back to Homer. We formed a human community, some dead and some living now. I was alive, I reasoned, and therefore I must write.

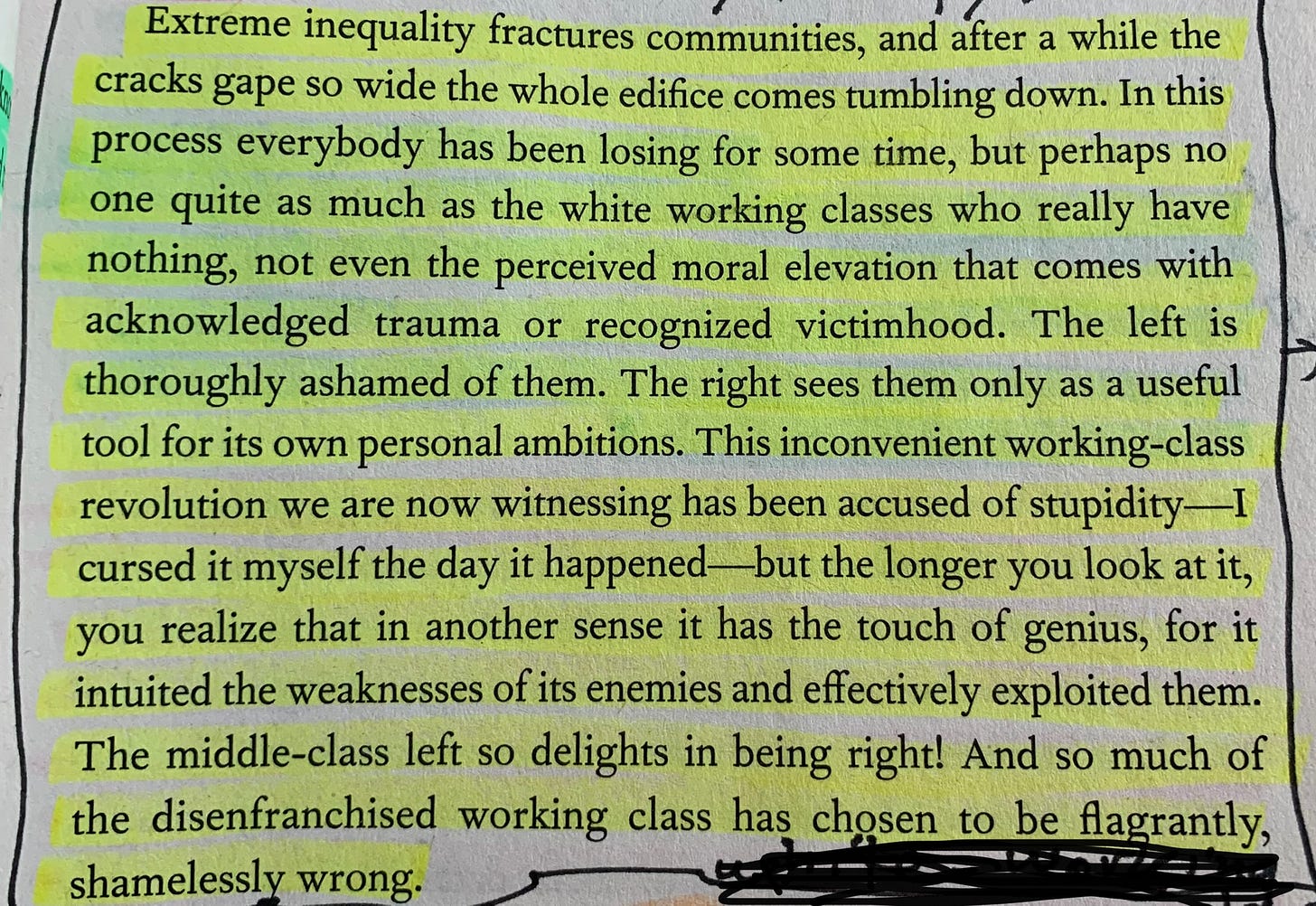

When the pandemic hit in March of 2020, I was living in Manhattan. East Harlem, to be specific. (I wrote a “fictional memoir” about this experience which I’d like to serialize here at some point.) I’d lived in Manhattan for exactly one year by then. It was of course a terrifying experience, living in New York in March, April, May of 2020. Life seemed to cease all around us. People were dying in staggering numbers. Hospitals were overwhelmed. Sirens, omnipresent. New York’s governor and the city’s mayor fought like enemies. After George Floyd’s brutal iPhone-caught murder, protesting, riots and looting exploded across the nation. In East Harlem, you could feel the bubbling tension; I felt the anger and resentment as I strolled down the cold streets, avoiding eye contact. These communities had been hit hard: Many were low-income, frontline workers, packed by the half dozen into tiny chopped-up apartments.

The days suddenly felt like weeks, the weeks like months. I talked with friends and family on Zoom and on the phone. I slept a lot. I took daily walks to maintain my sanity, even as East Harlem became violent and dangerous. Even as I became one of the only white faces I saw in my neighborhood.

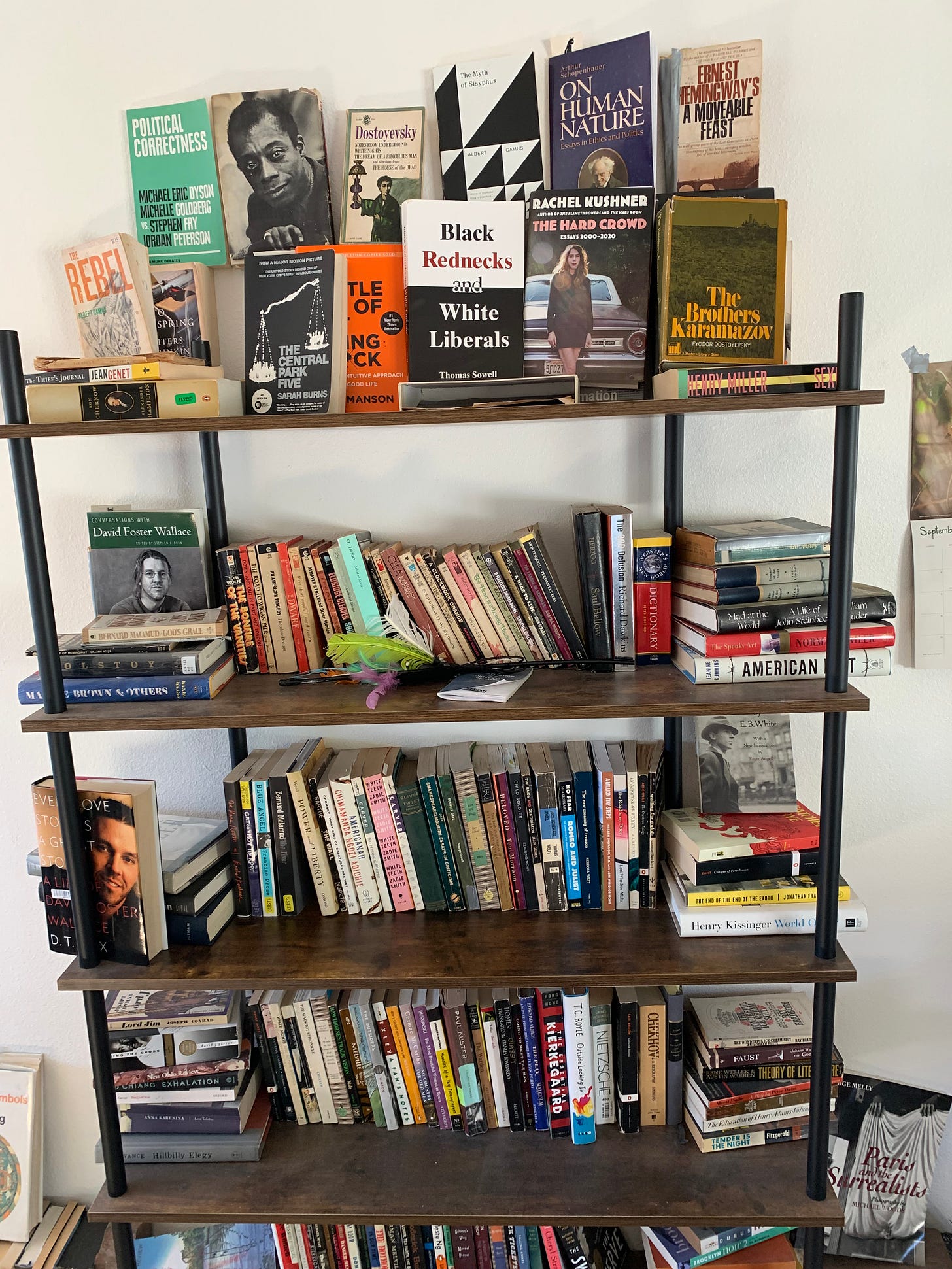

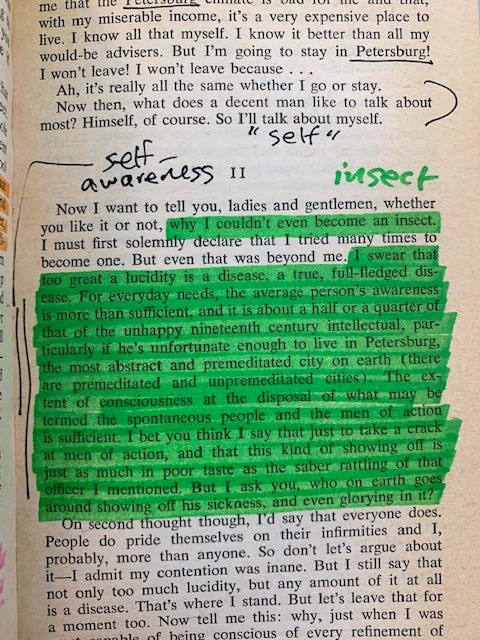

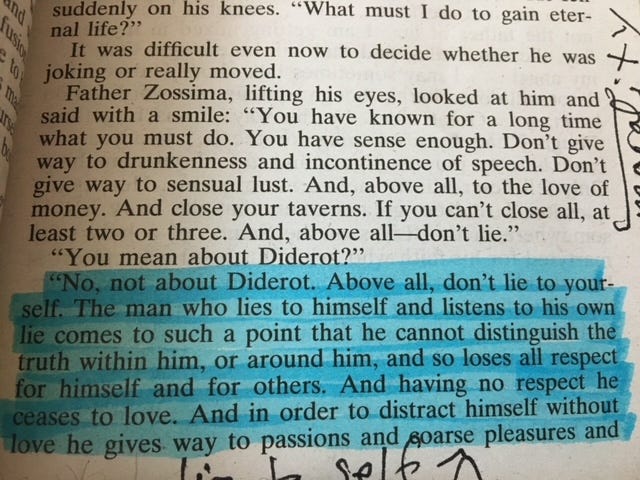

And, of course, I turned to books. Literature. I was one of the lucky ones: I had been working remotely as a writer and developmental book editor for almost a decade by that point. Staying home was normal for me. But not this much. During the time I remained in Manhattan during Covid—March, 2020 to June, 2021—I read more books than I had probably read all combined up to that point. I did not count them. It wasn’t about quantity; it was about being spiritually and emotionally and mentally transported. I first turned to one of my all-time favorites: Dostoevsky. The famous 19th century Russian author seemed to say everything necessary about life, art, death and love in every single book. First I reread Notes From Underground, which was perfect because the angry, bitter, resentful but insightful semi-genius narrator stuck inside his home and head reminded me of 2020, all of us being locked inside our cramped, stuffy apartments, unable to connect with each other physically, frustrated and confused.

Here's a quote from Notes From Underground:

“And the worst of it was, and the root of it all, that it was all in accord with the normal fundamental laws of over-acute consciousness, and with the inertia that was the direct result of those laws, and that consequently one was not only unable to change but could do absolutely nothing.”

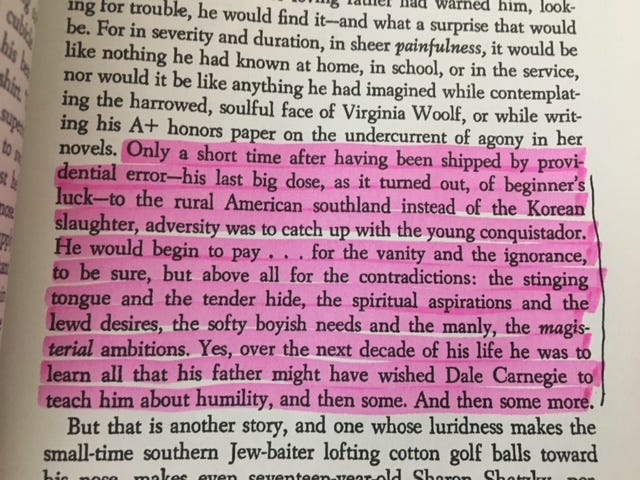

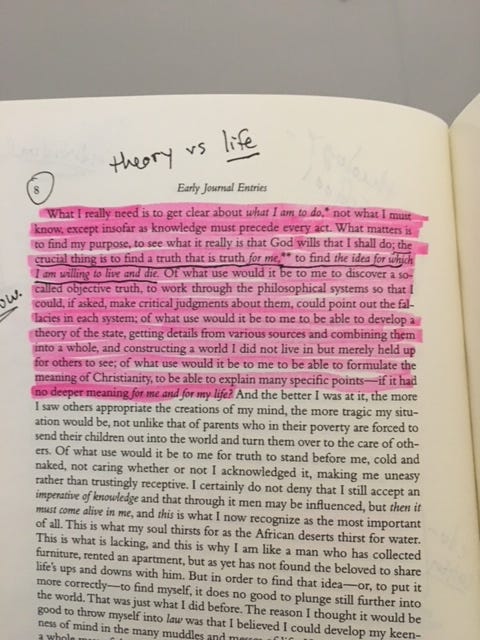

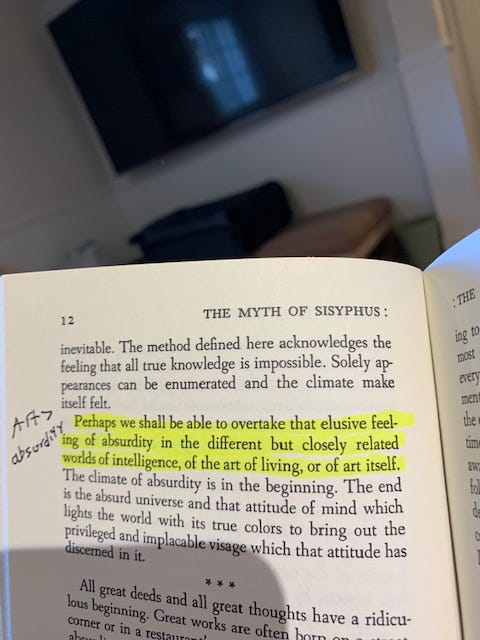

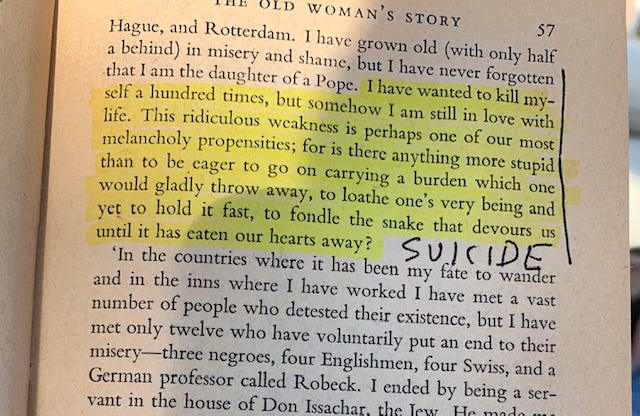

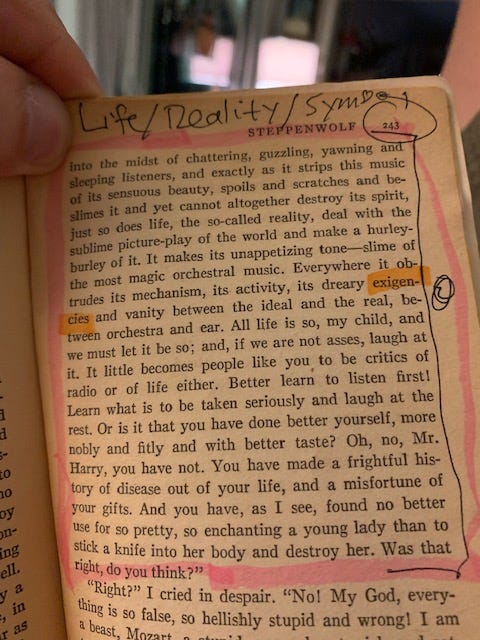

After this I read The Brothers Karamazov, perhaps Old Dost’s finest book. I chugged through Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, a profound door-stopper of a tome about a secret love affair doomed from the start. Tolstoy, like “Old Dost” (as I call him affectionately) was another signature 19th century Russian author who seemed to encompass pretty much everything in life in the 800 to 1,000-page epics he penned. They were the Homers of their time. I like to read both hard copy books and also listen on Audible sometimes. The Russians I read hard copy. I didn’t solely read: I took extensive notes in the margins with my black Pilot pen; I highlighted words and juicy sentences and sometimes whole paragraphs or even entire pages. I snapped photos of these highlights sometimes with my iPhone so that I could refer back to them when needed.

I reread The Catcher in the Rye, which I gulped down with much more pleasure this time—it’d been fifteen years—because I was A. An adult; and B. Lived in New York City which allowed me to picture every scene. I consumed Phillip Roth like a man chugging cold water in the desert after starving for three days (Goodbye, Columbus; Portnoy’s Complaint).

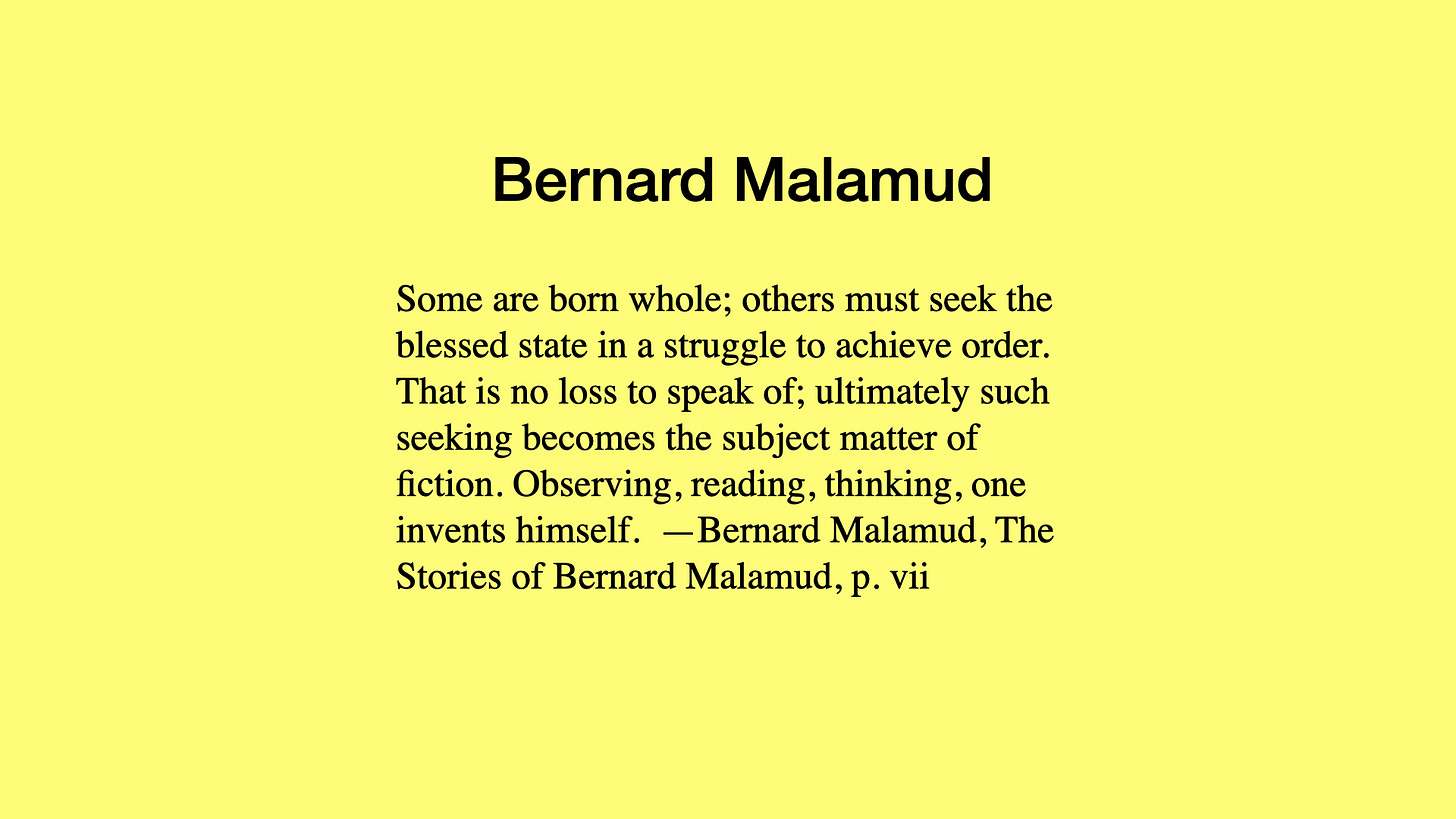

I finally read a book I’d wanted to complete for a long time but had never succeeded in finishing: Herzog, by Saul Bellow. I swallowed down Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer, about the horror of 19th century Jewish oppression in Russia. (The 20th century American Jewish writers were spectacular, of course.)

Mary: Herzog by Bellow and all of Malamud pretty much saved my life and brought me to writing:

I read Zadie Smith’s essay-collection (Feel Free, 2018) and reread Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son.

I reread Coates’s Between the World and Me, a gorgeous memoir told as a letter to his 15-year-old son in 2015. I read Henry Miller again—Tropic of Cancer and The Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. I reread George Orwell’s classic 1984 which made my jaw drop to 71st Street because: We are living this fiction now. I read biographies of Ben Franklin and Steve Jobs (both by Walter Isaacson). I read philosophy: Kierkegaard’s Either/Or; Sartre’s The Wall; Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus (about the practical morality of suicide); Voltaire’s Candide; Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract.

In short: I lost myself in books. It was as if I had returned to the womb, metaphorically-speaking. Outside, people were angry and alone and isolated and dying. Riots and mass protests were tearing at the very foundation of America. January 6th made the nation collectively gasp in horror. George Floyd was ruthlessly murdered in cold-blood. On the internet, people battled out racial and political ideas as if we were living through the second Civil War. Polarization—both political and cultural—increased to the point of breaking. It seemed for a while there that the whole ship that was America might go down. We all had nothing but our computer and iPhone screens, our tiny apartments and the inside of our own deranged, anxious minds. But I had reading. I had classic literature. Dead white men—mostly but not exclusively dead white men—held my hand and told me everything was going to be alright. Things in society had crumbled before, they promised, and society survived. They would crumble again in the future, and even then society as a whole would carry on.

If I could read challenging, profound books which struggled to grasp at life’s meaning, I thought, then I would always feel alive, and I would never be alone. In my twenties I’d read in order to go “out there” as Kerouac had, to live life, fall down, make mistakes, gain experience, produce some battle scars, to, as Joseph Campbell says, engage in my “descent into Hell and return.” In my thirties, older, wiser, more mature, I read to understand myself more deeply. And when I say “myself” I mean both literally myself (Michael Mohr) but also the fundamental concept of what it means to be human. I have a college degree in writing, but I didn’t need one. In my opinion writers don’t need a college degree. (Most of the famous 20th century writers we think of either didn’t go to college or dropped out: Hemingway; Fitzgerald; Kerouac; Bukowski; Miller; William Faulkner; Mark Twain; Ray Bradbury.) What I needed to be a writer was self-belief; discipline; life experience; and to write a lot; and read as much as I could.

More recently, my parents and I did something we’ve never done: We decided to “read” (listen to) a book on Audible. We batted some ideas around before choosing German 1929 Nobel Prize-winner Thomas Mann (1875-1955). The book? The Magic Mountain, originally published in 1924. The book takes place entirely at a sanatorium in Davos, high up in the Swiss Alps, just prior to World war One. Hans Castorp—the young protagonist—is slated to be an engineer but decides to visit his tubercular cousin who is staying at the sanitorium. Eventually, Castorp ends up staying for seven long (and yet short) years. (Mann plays gorgeously with the cosmic concept of Time.)

There are numerous colorful characters in the cast at the sanitorium. Revelations abound. The massive tome (roughly 1,200 pages, aka 37 hours on Audible) is steeped in rich symbolism, deep metaphor, and the exploration of countless major themes including death, time, humanism, radicalism, war, love, lust, the eternal versus the temporal, illness and sickness, morality, and on and on. One might refer to The Magic Mountain perhaps as the Brothers Karamozav of the 20th century. It did, of course, take Mann 12 years to complete the book. Reading the book one can grasp why.

Over the course of many months, my parents and I listened to this profound work, an hour here, two hours there, forty-five minutes here. It changed us, certainly. We bought the companion-guidebook simply to attempt to understand the book on deeper levels. If you want a challenge, read the book. (Besides Old Dost it might be compared to David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest.) My father was recovering from cancer and a debilitating disorder which resulted from the chemo. My mother was mostly homebound, caring for him. I had left New York City and was living locally near them, in Santa Barbara, to help as well. Plowing through a great piece of literature together—going on a seven year journey in 1,200 pages—brought us closer. It felt perfect for the moment: The mountain felt myopic and closed-in; separate from the “flatlands” (the regular world “down below” the mountain). We had just gone through 2020 and 2021, a global omnipresent sanitorium of sorts, for all of us, locked up in the mad funhouse that was our collective and individual psyches. For all of 2020 and half of 2021 I’d been living in Manhattan, a whole world away from my family on the west coast, lost and scared and alone, depressed, angry, confused and desperate. The political polarization going on and the madness of Trump and the war in Ukraine all reminded me of Mann’s foreshadowing of “The Great War.” So the book became, for me, a sort of companion to my current reality. This is what makes good, potent literature: Universality. The Magic Mountain was published just shy of a century ago, and yet the themes presented, the ideas discussed, the feelings expressed all felt real and valid right now, in 2022.

For me, reading has always been a companion book to existence. Books might be hailed as instruction manuals for life, in a way. Authors are magicians who pull the mysterious curtain of life back and show you the meat and bone of being alive. Blood, guts, truth, honesty: That, to me, is literature.

Happy reading!

P.S. I just finished another book I’ve wanted to read for a long time: Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf.

Would you like to do a Guest Post, write me at marytabor@substack.com

Or

This post was a terrific read - thanks, Mary and Michael! So much to provoke thought and to ponder.

For a long time I was shockingly inconsistent with my reading, but when I started reading again with purpose (purposes being to learn something, to chill out, to find joy in the words of others, to challenge myself, plus about eight thousand others) my brain - and indeed my whole self - was reminded of what the heck I'd been missing.

I also find it quite true (at least for me, but I think for most people) that I learned to write early on in life, but I had to gain some life experience to have something valuable to say, something to write about.