Note: You can start reading here or anywhere, then go back. See Table of Contents. Come in the middle? Robert is the narrator who discovers after his wife Lena has died that she had a lover, Isaac. Evan is Isaac’s wife. Robert is on a search for how he lost Lena: He’s creating the story through memory, invention and a search for the truth and his role in what happened—and by stalking Isaac.

Parsing Lena

She was inexorably bound to him but why? He wasn’t worthy and she was no fool. I keep thinking of her odd metaphors, of her stilted way of presenting herself to me before we married. I keep thinking the word barren. I recall the baby pillow, the gift from Evan, that she held against her chest when she was dying.

I build this story out of fragments: a baby pillow and a gesture, his hand on her head, the way he brushed a strand of hair from her forehead.

***

Lena watched Isaac go. The sight of his back, of him, moving away from her made her think of all his leavings. She recalled that time when they parted at Connecticut and Calvert; he, to go to the subway back to the office—they had had lunch together far from their home base—and she, to walk across the bridge because she thought that looking down into the Rock Creek park, into the trees, into the long drop to the river would help her sort things out.

That day when she was on Calvert, she’d tried not to look at him. She walked and tried not to turn back, determined not to make the revealing turn those in love can’t resist. She resisted until she’d walked a full block and then when she was sure he would be gone, she stopped and turned.

There he was walking rapidly towards her. He must have crossed the street towards the station and then crossed back. When she saw him, she waited. He said, “Let’s go round the block, find a place where I can kiss you.” She said, “No, too public, too risky,” but loved him for wanting it anyway, for his impulse.

Another time she’d left him at the corner of Connecticut and K, perhaps after helping him pick out a tie at Britches. This time she was going to the subway.

One of them must have always been leaving the other to enter the subterranean tube.

She crossed the street and didn’t turn until she was safely through the harried intersection. He was leaning against a building on the corner, simply leaning, watching her.

I had never looked at her this way, with unfailing attention, with something she now thought of as the slow-motion view of a peony blossoming, as if she could see the profusion of petals in his look.

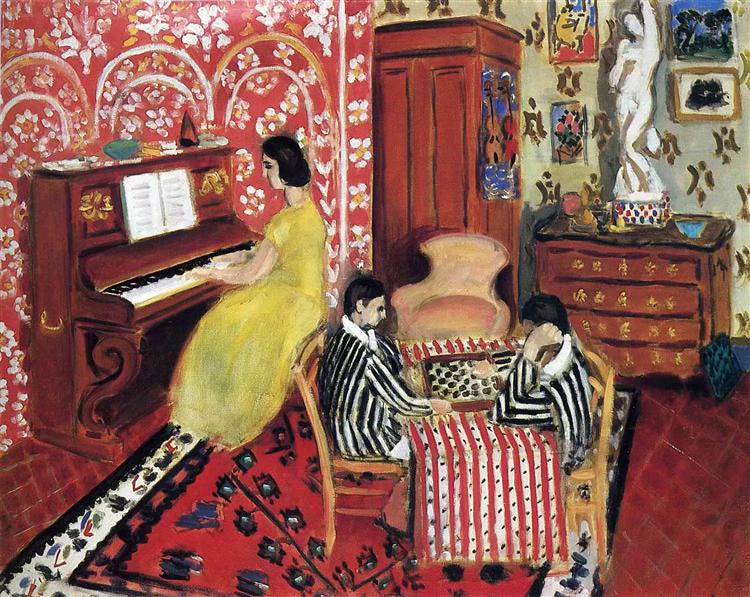

If I were to walk to the Smithsonian through the grassy mall that is lined with houses of art, the paintings we’d seen together, Matisse’s Pianist and Checker Players, the print that hung in our house, where we lived, cooked, ate, made love, would I have seen them on a bench?

I imagine she would turn away from him—in shame, I think. It’s this shame that’s made it hard for me to hate her—even though I expect more of her, a clearer sense of what is right, of what she ought to do.

Would I do as Isaac did? He leaned against her back, first with his arm, then his head barely touching her shoulder, his chest close to her back but not making contact.

A pitiable sight.

I see loss in Lena, a pose of exhaustion. I am exhausted.

I recall when Lena was beyond comfort after the death of each of her parents, most desperately, after the death of her mother. I’d felt then like a parent who resists touching an older child who’s been hurt because I’d not known how to come to her as a man—the impropriety of touching her body in the face of her loss barred me from union with her. But communion was all she’d wanted.

This was the way Lena’s father must have resisted touching her when she suffered from the depression that took her over, that time when she was seventeen. He could not put his arms around this child he loved, feared that the male parent touching the female grown child would be improper because of where she’d gone—to the depths of her brain, to somewhere he couldn’t know and that she couldn’t explain. To touch her would be to invade, to violate her, because he would not have her full presence, her ability to pull away.

If I had seen Isaac and Lena on the bench, Would I have placed one arm on Lena’s bent back and then in my own helplessness leaned my head on her shoulder?

A gesture of paradox.

***

She was my breath of blue.

***

When I was a child, I saw this blue, but didn’t know how to name it, in a blue jay. I would have called it a checkerboard-blue because I saw things squared, placed, certain, the blue and the white. You can’t see the colors of the checkerboard in Matisse’s painting.

I lived in a three-street-plus-main-street town, where I watched the controlled burn with my father.

My father and mother live in the big narrow-lap bevel wood-sided old Victorian that rises up like a steeple, announcing itself to the town, to the world.

My father owns land, the farm. And his land like all the land around the town opens up in one long field of alfalfa and corn and soy beans, squares of green patched up against pale gold, stretching so far you’d think the world was flat. My mind’s eye can see the sky, the fiery blue at end of day, the way you have to turn your head to see it all, a perspective that in its width and breadth paradoxically narrowed my view because I thought all that could be seen was visible.

My father had a rifle but he taught me to shoot with a B-B gun. When I was older, I used the rifle when we hunted. He taught me to shoot in the barn on the south farm where the barn swallows fluttered in the hay mow, nested in the rafters—awkward in the barn, graceful in flight like the white-tailed tropicbird I saw in Anguilla that seemed to stand mid-air above the aqua water and then with the dip of wings caught the light of the sea, the color aqua in a parabola on sky. My father shot the brown, fork-tailed swallow in the barn, straight on, quick, sure and showed me how to cock the gun, raise it, press the butt hard against my shoulder, hold my elbow high and level with the barrel, shut my left eye to get my right one looking through the V of the rear sight that sat on top, how to hold my breath, how to aim and strike.

I went out one day and sat under the old oak that rose up higher than the roof of our house. I watched the checkerboard blue in that blue jay, aimed, lined up my eye with the front sight, squared, pulled the trigger slow and sure, killed.

My father said, “You waste.” I didn’t know the difference between barn swallows and blue jays. But he saw one as a nuisance and the other, not, though he’d often complain of the blue jay’s harsh attacks at the feeder on the tiny nut hatches, finches and indigo buntings. In the barn the swallows were a nuisance. In the open land, the blue jay was not. He told me the fable of the grasshopper and the ant, how the grasshopper took and ate and wasted while the ant hoarded and prepared. It wasn’t the killing that bothered him, that he lectured me about, it was the unwarranted waste.

I killed solely for the aim, the narrowed sight.

I once saw Stan Musial play for the St. Louis Cardinals. My father took me to that game in the 1950s when I was eight or nine and Stan was playing the outfield, not pitching anymore. A batter was in the box when the umpire called a time out. Stan had signaled the umpire and then leaned down to tie his shoe. He’d stopped time from the outfield with a loose shoelace.

If I’d seen Isaac and Lena walk on K Street, stop at Britches, the men’s clothing store, if I’d seen Isaac inside the store lean down without a word to tie the loose shoelace on Lena’s black suede oxford, heard him say, “Double knot,” seen him pat her ankle, would I have known that Isaac stopped time? That with this move, Lena remembered all the times her father, who sold shoes for a living, would prop her foot up on his knee, when she was sitting on the couch at home, or on the metal chair on their front stoop, would wrap her tiny ankle and her shoe in his hands, check the fit of her shoe in an embrace. That Lena became childlike, ready, when Isaac tied her shoe. That this moment aroused her more than my hand on her breast in the kitchen when I wanted to make love. Would I have understood why, when Isaac saw her, said “Look at you,” he moved her?

What I wasted was the look. But I was efficient with time.

When I made love to her, I ensured that I brought her to pleasure, as I’ve explained. This process, in fact, does not take long. When I was done, I got out of bed, took a shower, had my coffee.

I had made love tenderly to Lena, much as any woman could hope.

That would be the sort of thing Lena would have thought.

But I made love efficiently. I know that now.

I know that Isaac, perhaps out of guilt, perhaps out of the fear of the sight of me in the Tabard Inn, perhaps out of a desire to live the life that he calls his “so-called life,” will make love to Evan and that he will tell Lena about it.

I never played, as she’ll imagine Isaac and Evan did. But then she’ll know that she can never have him. He can’t exist for her. He is like a death. Like her father and her mother who died.

Lena must have known this.

Lena. A blue bird, small, fragile, how she sat, waited, fluttered, faltered, looked. I could see her even as I took her in my sights, took aim, took her to climax.△

Lena’s Baby: Chapter 12, next

Table of Contents

Love,

“The narrowed sight” kind of says it all, doesn’t it? Brilliant chapter, love the checkerboard-blue, Robert’s view is so tidy, efficient and boxed in, but maybe we can’t blame him…you reveal his father, the crop rows, the controlled burns. Seems this fear of the chaos of “red” has been building for generations.

Mary, you've managed to pack so much vulnerability in one chapter. I find it interesting that both Robert and Lena are so affected by their relationship with their parents and how this unfolds as we read. The other thing which strikes me is the contrast between Robert and Isaac, how much more similar Isaac is to Lena's father and mother and how in her grief, his spontaneity...the connection with him must have felt like a balm.