Starting Late: Elegy for Iris: Lesson 17 Part Two

The risks we take, why it's never too late, two writing experiments (Part Three of this lesson to follows--still time to read the book or watch the film)

Starting Late? What’s stopping you and what are the risks?

Why it’s never too late:

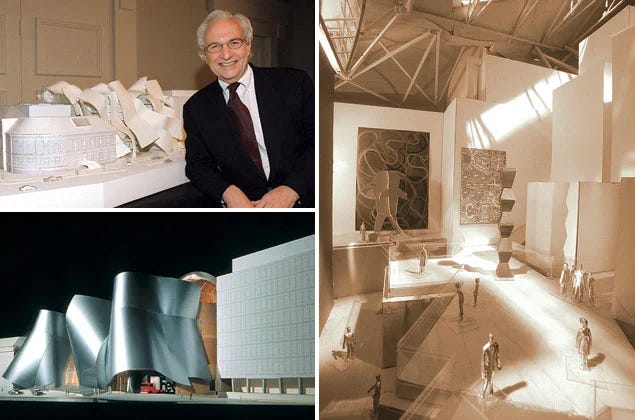

Did you know that in 2005, the architect Frank Gehry’s addition to the Corcoran Gallery was nixed? That was the bad news. Here’s the good news in an article I saved by Benjamin Forgey, past architecture and art critic for The Washington Post: “Rather late in life, the 76-year-old architect transformed himself into the avatar of an aggressively experimental, emotionally charged, formally inventive architecture that challenged conventional orthodoxies of both modernism and postmodernism. Challenged and then changed them.” Forgey described the design as “huge metal sails billowing elegantly outward, catching the light in wonderful ways, and looking right at home in supposedly conservative Washington.”

Before I turn to Elegy for Iris, let’s return to how I introduced “Starting Late” with this essay on Ageless Creativity and then again in Lesson 12 of Write it! How to get started:

Before I move on in the course, Check out these movie reviews for The Whale and The Banshees of Inisherin in this section Literary Essays.

I turn full circle to what may silence us.

Table of Contents for all 19 lessons

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mary Tabor "Only connect ..." to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.