The firemen were mostly older and younger men I knew, had grown up with—perhaps a few out-of-towners, sure—but mostly guys I could tilt a howdy finger off the steering wheel of my father’s pick-up—the old blue one I like to drive around when I’m in town, rare as that is now.

My father didn’t see fight-fire in the War, the second big war when he flight tested P-51 Mustangs, the fighter plane, but didn’t shoot its guns.

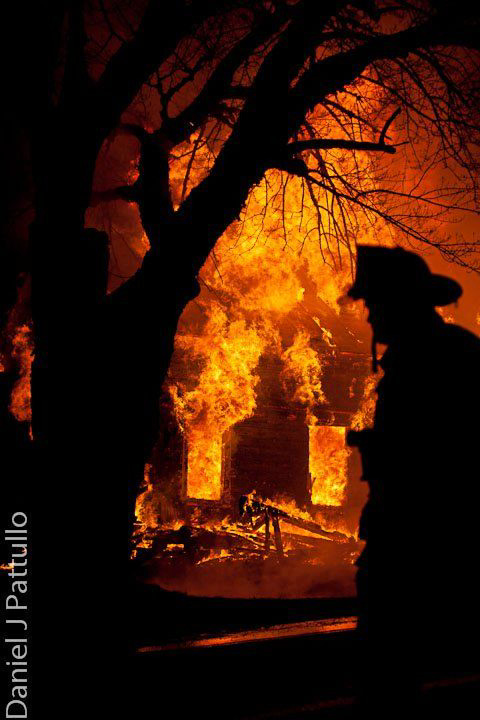

These guys, the firemen, let me get closer to the fire than most other onlookers—although I was surprised by how they trusted the oglers. They trust their neighbors to have good judgment. That too amazes me because I now live in downtown Washington—the center of politics and corruption.

My mother didn’t come to watch the fire.

My mother’s mouth turns down at the corners. She says she doesn’t smile because there are gaps between her teeth, and indeed there are, but she doesn’t smile because she has accepted what she views as her lot: That my father will rise early and make coffee, that he’ll scramble an egg in the microwave while she sleeps, that she will always make him his peanut butter sandwich for lunch, that she’ll eat her Hershey bar alone in the kitchen while he listens to the evening news, that these will be the things they’ll do and that each time they occur, the daily moments of her life with him, they remind her that she doesn’t love him.

She had nothing to learn from the fire.

I had much to learn.

Oh, the plot thickens... Have to run on to the next!

Hi Mary. That LONG sentence is wonderful, capturing the repetitive minutia of a longs d hopeless resignation.