In her office, Lena was held by a phrase of translation: And from beneath the throne came forth streams of fire, from a fragment of Enoch in the Dead Sea Scrolls, a dream vision. She tried to continue working but this vision of the chariot throne, coming like fire, like lightening, the way it kept coming, frightened her.

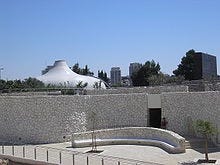

Lena was working on the exhibit of the Dead Sea Scrolls coming to the Smithsonian, though the exhibit was pretty much set—it was in Chicago. She spent her time considering small changes in the layout that would allow the exhibit to fit into the Sackler Gallery’s set-up where it was to be displayed underground, like the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem where they’re permanently housed, underground, like a cave—the subterranean. The underside of her life, the side she shared with Isaac, her lover, belonged there.

The halls were well-lit, but windowless and, like entering sleep, she entered awake and fell into dreams. At work, she dreamt awake; at home, she dreamt asleep. The Scrolls and the Bible, full of visions and dreams, made her dream more often, more vividly, in color: beryl and sapphire, flame-red and shades of ochre, colors that filled her dreams. Each time she dreamt these colored dreams, awake or asleep, she woke with an ache in her chest. Though disturbed by the dreams because they left her feeling something missing, out of reach, she began to count on them to fill in the blank they created.

While she drifted, day dreamed, I imagine Isaac arrived at her office door. I imagine her looking at a blank wall, him standing, watching her.

Here’s what he’d have done that morning.

Isaac works in a lab in the basement of the Museum of Natural History, across the Mall from the Sackler. He’d have said to himself, “I’m mad or this is a damn dream,” Lena’s words, the end of order. She was on his mind. She was always on his mind.

She is always on my mind.

Maybe he should go home, work in his garden, build the wall for the espaliered apple trees that would border his field of lavender, the trees on the outside of the wall.

He’d get out his digging bar and use its round end to pound the stakes he’d use to mark where he would plant the trees. It wasn’t the best tool for the job but its heft had gotten him out of jams, building confusions, when he’d had to pry himself out of a mistake. He’d used his prybar to get the leverage he needed to take out the mistake and then his digging bar for a new hole and he’d realign where he’d begin again. He saw the heavy tool, some twenty or thirty pounds of metal, in his hands, how he would swing it on top of a pole to begin a hole in the hard soil. This made him think of building a house. Maybe he’d build the greenhouse for his wife Evan, the one she’d wanted for so long, maybe the holes would be the first step, his marks for the foundation set firmly with these holes, the way he’d begin.

Next: “The Lovers” prose 4 of chapter three

Table of Contents

Love,

Such a perfect sentence: "At work, she dreamt awake; at home, she dreamt asleep." :)

I find new layers in your words every time I reread a passage. Today, this sentence really struck me, as if Lena’s affair, while underground, is trying to awaken her, breathe life back into her dreams, while at home, in the light of day, she’s asleep to her needs, her longing.

“At work, she dreamt awake; at home, she dreamt asleep.”