Note: You can start reading here or anywhere and then go back if you like. See Table of Contents. Come in the middle? Robert is the narrator who discovers after his wife Lena has died that she had a lover, Isaac. Evan is Isaac’s wife. Robert is on a search for how he lost Lena: He’s creating the story through memory, invention and a search for the truth and his role in what happened—and by stalking Isaac. Chapter Seven, longer than usual; so, to read use website—or simply listen on the app.

The Music Lesson

Karen, the dentist, was Isaac’s lover before Lena died. I know this because I saw them kiss at the Tabard Inn while my wife lay ill.

His story can be built. It is easy to imagine. An affair he’d ended once, before he met Lena, maybe when he met her, an affair he’d begin again, while Lena died or, more likely, even before.

“Remember when I made the veal scaloppini?” from the conversation I overheard. He must have known Karen before. The Tabard Inn was “their place.”

Now I can place Karen back in time, back to the day I know Lena had been to the farm, before she fell ill. This is the story I reconstruct, the story of the man who betrays his mistress.

△△△

On that day when he took Lena to his farm, when he took that risk of discovery, Karen had called him at his office, said she’d be in town, said, “Why not meet me for a drink?”

He’d have said, “How’s the marriage?”

“Oh, Isaac, really. Just come.” He decided he needed to understand the greatest danger in his hierarchy of risks: If he loved Lena, he was in trouble. Karen would have been an exercise in comparison, so that he could be certain.

Certainty—this matters to him. To know what he is about.

At the inn, after the drink, Karen asked him to dance, a fox trot. She felt thick in his arms, not like Evan or Lena. Lena hums in his ear, in my ear.

He tried to remember how to dance.

My mother taught me to fox trot.

While Karen hummed, he whispered these words: “Slow, slow, quick, quick,” keeping time to the music with Karen’s voice in his ear.

I hear my mother’s voice. She’d often called our dance lesson, “The Music Lesson,” referring to our work together on the piano but also the Vermeer painting we’d looked at in one of her art books.

I’d seen that painting with Lena in the National Gallery at an extraordinary exhibit of Vermeer’s work collected.

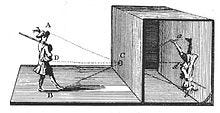

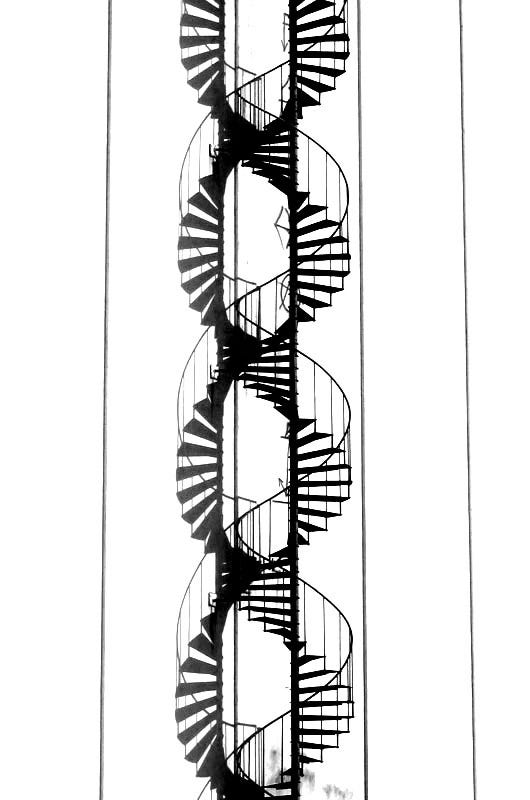

I recall now a lesson in perspective that accompanied the painting: A sharply receding perspective makes the room look large and deep. Vermeer used orthogonals, the right angles that can be drawn in the pattern on the floor to a vanishing point, and that point provides the key to the painting.

The eye is directed to the couple, student and teacher, at the far side of the room, behind the cello, behind the table in the foreground. The table in the foreground is large and formidable with the heavily detailed pattern in the Persian rug that covers it. But the vanishing point, the place where the eye lands, is the woman’s sleeve. She stands playing. Was it a clavichord?

I watch Isaac touch the silk sleeve of Karen’s blouse and she vanishes in his arms.

I see my mother, then Lena, one then the other.

When my mother danced with me, I was a boy, about twelve, and she was a thin woman with tiny feet for her height. I was as tall as she was, almost 5'6" then but I grew to six feet in my teens. She sang the tunes out loud so I could learn, go to school dances and ask a girl who sat along the wall in a folding chair. At home, we didn’t have a record player—my father thought it frivolous and unnecessary—and the radio wasn’t reliable for the right tune at the right time. But my mother had all the words and tunes memorized.

When she thought she was alone, thought I was upstairs doing homework, I’d come downstairs, drawn to the timbre of her voice. She’d twirl around the kitchen floor humming Cole Porter tunes to herself, “You Do Something to Me,” or another, making me wonder who it was who mystified her.

I was mystified, when I was twelve, by her thin legs, her perfect little rhyming feet. She made me think of a spinning toy that defied gravity while it whirled. At the school dances, I chose the thin girls and tried to remember how to move my feet the way she’d shown me.

Isaac tried to remember how to move his feet.

“Relax, Isaac,” Karen said, “it’s a dance. Don’t worry, I’m not going upstairs with you.”

How could he want to go upstairs with her?

But Isaac is Isaac. He wouldn’t dismiss the possibility.

She leaned against him, her breasts, larger than Lena’s, spread wide, soft against his chest.

My mother. The feel of her small breasts, the sense of her sex that I couldn’t acknowledge when a boy, rise in my memory.

I pull Lena to me. The pressure of her small breasts, the rise of her nipples when I pressed my hand in the center of her back. I smell the spice in her skin, in my mother’s skin, perfumed with chocolate and brown sugar. She wasn’t much of a cook, but loved baking cookies, and loved eating them. She often ate a cookie instead of the memorably horrid casseroles made with Campbell’s soup or Jell-O—the spinach, white-green, no-one-is-sure-what’s-in-it-and-I-sure-never-wanted-to-know-casserole and then the salmon colored dish with olives oddly suspended—that she’d prepared for dinner. It’s the cookies that got us both through. I’d dust flour and cookie crumbs from my shirt after we’d whirled around.

After Lena and I danced, I’d brush off my wrinkled suit, a memory-gesture, and she’d say, “Are you wiping me away?” I’d answer out of memory, “chocolate chip and lemon crescents,” and she’d laugh, perhaps understanding?

I think now, yes, Lena understood.

But it is Karen who is in Isaac’s arms. She said, “They have rooms here, but I’m not going up with you.”

The Tabard Inn has a restaurant with a small dance floor and spartan but charming rooms upstairs. It’s an old inn, been there on N Street for years.

This was where Karen stayed when she was teaching at Georgetown’s Dental School, one semester, having left her practice in Boston to improve her résumé with a post-graduate credit that would later help her get on Boston U’s staff, where she is now.

He’d likely met her on the subway. He was standing. She was sitting, reading. He repeated the title of her book, “Speak, Memory. Does it speak?” She’d laughed, read from the book, “A sense of honor equivalent, morally, to absolute pitch.” He’d said, “I think my mother had absolute pitch on both counts.” “Both?” she’d asked. “The pure note,” he’d said, “and the right move.” “And you?” she’d asked. “Complete failure,” he’d said. She laughed again, leaned her head at an angle, looked straight in his eyes. Her pale-blond hair fell across her forehead and he leaned forward as if he might brush it away. She would have told him later that that move, that lean, that touch that did not occur but could be seen in the gesture was perfect pitch on both counts.

△

I have perfect musical pitch.

△

“What makes you think I want to go upstairs?” Isaac said while they danced. “You’re a married woman now. And I have perfect pitch.”

“Oh, but you don’t really—not in the musical sense.”

“In what sense then? Flatter me.”

“The touch.”

And he would be flattered. What should he say to this? “But I was married,” a non sequitur that made sense to him. She’d wanted to marry him—the reason the affair ended first time around. He’d had no intention of ever leaving Evan. He’d wondered then if he couldn’t love her because she was single.

Yes, he’d think, Lena is married, stating the obvious.

He must have thought about the fact that he’d be likely to bump into Lena when he took the Smithsonian job. Another affair he’d ended, an affair he’d begin again.

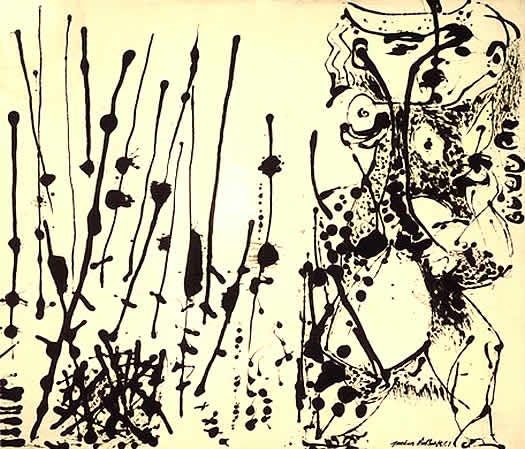

He’d first met Lena there, before she’d married me, when he’d come over to the Mall from the University to meet his friend John for lunch—the mummified cowboy case—and they’d probably wandered through the East Wing of the National Gallery and then up the escalator for lousy but artful food and after, down two floors for a quiet moment in Lena’s favorite room, where the modern art was—the two Rothkos, the two Pollocks, the Andy Warhols—and where the people weren’t.

She would have been all in black and reed-like thin, standing in front of Pollock’s Number 7, black on unprimed canvas, that she loved because of the abstraction of vertical lines like Japanese ink drawings and the illusion of a human form.

He’d have said something about liking the painting to her and John would have waved good-bye, guessing his intention. She would have said, “Not like his others. Simpler,” and that’s how it would have started, only to end about a year later when he got hold of himself.

But, in fact, he’d hardly gotten hold because she would not have been easy to get off his mind the way the other women he’d had were, the way Karen had been.

Did he hesitate before he took the job, before he walked across the grassy mall to her office behind the Smithsonian Castle? He’d have seen her leaning over a bunch of maps on her drafting table whose lamp lit her skin, clear as light, translucent, just as he’d remembered it when they’d had that brief affair before she’d married me.

“And now, so am I,” said Karen. “Married like you.”

He lied. “I don’t know anyone who loves sex as much as you do.” But he did, of course. Lena.

He would not have been so sure about Evan who, I suspect, wanted always to make love. Here’s how he would have thought about his wife: She always asked first as if making love were like going out to dinner. He considered offering her a menu before, repeating today’s specials while she read. “And would the lady like the fellatio? The cunnilingus?” He was sure of her answer. “None of the specials, please.” He would like to be touched. He would like to play poker beforehand with no mention of sex. He liked games, liked gambling.

Lena introduced me to games before sex. She played Gin Rummy with me. Always won. I taught her how to play poker, made a crib card for her. Though her memory was quite good, she was never sure whether three of a kind beat two pair, and how does one ever get that flush I’d explained over and over again? Lena blushed, a bad thing for poker, a child-like, endearment for lovemaking. I made love to her the first time after we’d been playing, after she actually got the flush on five-card draw and blushed from sternum to brow. She laughed, that kind of giggle that bubbles up in children. And then, after she raked in the pot (we’d put all the cash in our wallets on the table and played with it), I took her face in my hands and lightly brushed my lips on hers—not a kiss exactly. I was so taken with her ingenuous love of winning that that touch alone and then the way she looked at me, just looked straight in my eyes, that I’d thought right then, If I never get to do more than kiss you, it would be enough. And then I’d said exactly that, adding. “I’m lying, of course,” but I wasn’t. And she’d said, “The pot’s right,” a phrase I’d taught her for the ante-up before the play. She always forgot and I’d have to tap my finger on the table—or the bed—and say, “Gotta make the pot right” and then she’d laugh and toss in a dollar.

With Karen and Isaac, it was different—and probably still is. She and Isaac played rock and roll on the radio in the room, the Schubert in G flat when he was in her apartment in Boston, drank scotch, rocks, and took all their clothes off.

He didn’t remember her clothes, her underwear, anything except the way she let him do whatever he wanted and sometimes gave directions, making clear what she wanted. He’d say, “Is there anything else I can do for you?” and she’d laugh and tell him.

So unlike Evan.

Did he wonder if he should or shouldn’t be there with Karen, as if the oughts and shoulds of living had anything to do with what one deserved?

This is Evan’s way.

I like to say, Luck is more important than just desserts. Lena thought about the deserving, the undeserving and often found herself lacking. Is that why she didn’t question me about the absence or at best infrequency of love making?

I rarely touched her in those last years before she got sick and she rarely asked, unsure of what she’d done to deserve the loss. I hated that word “deserved,” as if anyone earned anything in life. Yes, money, respect. Yes, I did believe both were worth earning but was never sure I deserved either when I’d banked my checks or saw the brow of another bend ever so slightly—that moment when one perceived that another has looked at you anew.

Evan often looks at Isaac this way.

Once, when he’d helped their son Jason figure out how to write his college entrance essay by asking him this question, “What is the one thing you did in high school that took the most courage for you to do, however small, however insignificant it seems to you?” and Evan had been standing in the hallway listening, when he’d come out of Jason’s room, when she’d looked at him and then that barely noticeable downward tilt of her brow—she’d made him smile—that simple move of eyes and brow and shoulder. She hadn’t said anything. She didn’t need to. She knew that he knew.

It is this about Evan that binds him to her.

When Karen kissed him on the mouth, touched his lips lightly with her tongue, he remembered that Lena had suggested the question.

Lena told me that Isaac was troubled over Jason’s essay, that she’d had an idea. He took from her. He took too much.

How had he earned what Evan gave? He’d violated Evan with respect taken, unearned.

Karen’s kiss made him want Karen again. To get and not deserve. And her tongue, ever so briefly, at the end of the kiss. He didn’t remember her doing this before, the swift move at the end of the kiss, lightly seductive. It was Lena’s move and he was confused by it.

He stopped dancing, stepped back. “There’s something I have to tell you.” They were standing in the middle of the tiny parquet dance floor.

“That you want to sleep with me.”

And now I imagine myself inside their story when I had no suspicions of my wife’s betrayal, when it would not occur to me to ever follow anyone. But whether I were there or not, I was on Isaac’s mind, the man who kept Lena safely married.

“No, about the man,” Isaac said to Karen that same day he’d taken Lena to the farm, “the one who came up to us.”

“Come sit down,” she said. “Let’s finish our drinks. No, let’s get you a drink.” She’d finished her glass of champagne, called the waiter over, ordered another and a scotch, rocks for him.

Isaac walked to the table with her but didn’t sit. He wanted to go, not drink.

“So, what about the man?” and she leaned towards him to kiss him again.

He sat down at their table. “Don’t.” He’d not go upstairs with her. He believed she’d lied when she’d said she wouldn’t go. A test, of sorts. Karen’s sort of game.

Lena was on his mind, Lena, the woman at the piano in the picture. Which picture? The Music Lesson?

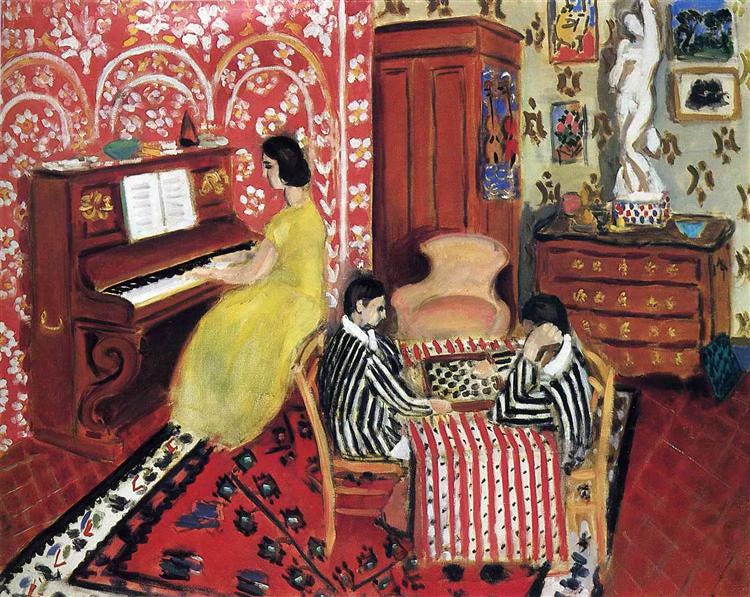

No. He saw Lena’s Matisse print. He was like one of the two men at the table, both in oddly striped black jackets. He’d never before thought of them as prison uniforms—a ridiculous way to view the painting—but he’d always hated those silly jackets Matisse chose for them. The jackets linked the two men, locked, hand-cuffed.

He and I are hand-cuffed.

“Oh, forget it.” What did Karen have to do with this? He had to get away from her, back to Lena. He must talk with Lena. “I need to go.”

“A kiss scares you off so easily?”

“Karen, I’ve met someone.”

“Well, I’m married now.”

“No, I mean I’ve met someone I love—and then there’s Evan.” He was cruel to say this. If Karen had ever loved him, this would hurt her. For the first time he used the word, the unsayable word, aloud for Lena though she’d not heard it. He hurt Karen needlessly. He’d said it for himself, a selfish thing to do. He didn’t see any way to undo the harm or to take back the word now spoken.

But what did he know of love? What did I know of love? We are bound in this question.

Their drinks arrived but Isaac didn’t touch his.

“Will you leave Evan for her?”

“She’s also married.”

“Like me. Shall we have a toast?”

“Yes, I suppose. To marriage,” and they clinked glasses, but Isaac didn’t drink his scotch. “Married, like you. So how’s the marriage?” he asked. “You wouldn’t answer that question when you phoned. Well?”

“He loves me or says he does. He makes lots of money. A doctor. I enjoy him, but I did want to see you, didn’t I?”

“Curiosity, I suppose.”

“Yeah, curiosity—on your part too, I suppose?”

“Yes, I suppose.”

They were flirting now. He thought perhaps he might go upstairs with her and sipped the scotch, the cool liquor on his tongue, the memory of their coupling. Why not? Another betrayal? Would it really matter?

“Tell me about this woman you’ve met.”

He didn’t want to talk about Lena. Enough, with the pronouncement of his love for her. And he didn’t want to explain that he was being followed.

If only I had been smart enough to follow one of them then—yes, even Lena—when I could have changed things.

He was in a muddle. So he diverted her with an obscurity. “The man was curious—the one who came to the table.”

“Curious about you or me? Perhaps he was someone who wanted to flirt with me.”

“No.” He finished the scotch quickly, one swallow.

“How can you be so sure?”

“I’m not sure of anything. Never have been. You know that about me, Karen.” He was back on safe ground. They were playing again.

“You’re not going upstairs with me, are you?”

This surprised him, not like Karen to stop the game. “I don’t know. Am I?”

“Isaac, I think of you more than I’d like to admit. Things come back to me, the way we …”

He leaned towards her, took her hand, said, “Speak memory.”

And she laughed.

“Come on, let’s dance again.” He took her hand, gave it a tug and they began a slow jitter bug to “How Do You Keep the Music Playing?”

“A matter of consequence, this dance,” she said, “for it may be our last.”

A matter of consequence. Why would she put it that way? Had he ever mentioned to her the book he’d read so often to his children? He didn’t think so. But that phrase: how the man talking to the strange little prince from a star must assert himself with those words: matters of consequence.

How when he was a boy and began to fool around with the watercolors he’d found in his father’s workroom in the basement, his father had said, “Nothing comes of it, nothing will.” It would never be a matter of consequence.

My father made that clear to me about the piano. “Something your mother does.”

Isaac learned. He is quick to make pronouncements, his likes and dislikes, on paintings—like the Matisse print in our living room.

Oh, to sleep with Karen and forget.

“Shall we dance?” Karen sang in his ear as he twirled her under his arm. “Maybe we should find that man you’re so worried about. Pull him in?”

He wouldn’t want to talk about me.

He said, “And then what happens?”

“We’ll dance the dance of three or more or none?”

“Or none? Then the dance is over,” he said and let her go.

Isaac could see that Karen toyed with him, that she knew he would lose Lena. His fear: That he will lose her, that she will choose to be sane and good.

She took his hand and walked him back to the table. “Oh, consider it a game. Let’s talk as if the dance continues.”

The dance was over, but the game? He said, “Since I always think everything is about me—” Something he used to say to her, making fun of himself when he was about to bring her to climax, to relax her, to allow her to let go. She’d laugh and then give herself over to him.

She laughed.

Isaac liked that. She’d remembered. He was thinking they will go upstairs. “The two don’t pull in a third to their dance,” he said, “because the woman and the man are alike.”

“Yes, perhaps,” Karen said. “And now, Isaac, I’m going to my room.” She got up and shook his hand.

He knew what he was about to do.

He watched her pick up her key at the desk, one of those large European type keys that get returned when one comes and goes, making him think of the ceremony she’d created, as if she’d planned the whole thing, knew that his eye would follow her to the desk—and because she didn’t look back, her self-assurance—knew he’d want to come with her to her room.

With her back to him, she was like the woman at the clavichord, his eye was drawn to her sleeve, the center of his vision and the vanishing point.

He took the stairs but did not hear his step. He heard her key turn in the lock.▵

Revenge? Chapter 8

Table of Contents

Love,

I think your story takes an important turn here, as we realize the complex tangles in Isaac's life. Seems like he's getting caught in a web of his own making and struggling to understand events, histories, himself. He has theories about everything, but are any of them grounded? All this along with Robert's journey and his role as narrator of unknown reliability. He has theories too. You weave so much together here -- it is fascinating how you do that. It has the makings of tragedy? redemption? something else? Can't wait to see where it goes.

So many layers of narrative unreliability and entanglement here. Love how the key turns but not necessarily the pins of the lock--this time.