Why make art, something “other”, when faced with the dilemmas of existence, with, as I’ve said in one of my short stories, “all the ways that life betrays the living”?

Some thoughts on the struggle for meaning, for a narrative in our lives, and the question I pose for all of you putting pen to paper. I ask this not from the perspective of a philosopher, but from that of a writer of fiction and literary memoir and my own search for a moral framework—for a narrative of hope.

In my memoir (Re)Making Love, I found myself turning again and again to Friedrich Nietzsche’s works

—along paradoxically and laughably too! with a bunch of rom-coms—believe it or not.

The draw to him was inexorable.

He questioned the foundation of the moral thought that preceded him. He did it big-time with his oft-quoted assertion, given to the madman: “‘Whither is God,’ he cried. ‘I shall tell you. We have killed him—you and I. … God is dead.’”[i]

I quote him, not as a non-believer, but as a searcher. I’m Jewish by heritage and tradition—not observant, not even as well-schooled as I could be, but a believer nonetheless.

Nietzsche again: “‘[W]ill to truth’ does not mean ‘I will not let myself be deceived’ but—there is no choice—‘I will not deceive, not even myself’: and with this we are on the ground of morality.”

Nietzsche’s questioning resonates for me because he asks, Is a coherent narrative for our lives possible? And if we’ve got no clear answer, what then?

Just for the heck of it, let’s go back to the “royalty” of modernism—heady stuff: Kafka (Arguably predates modernity), Woolf, Joyce. I’m not saying everyone who writes will read these folks, only that I did and have some thoughts.

Yep, that’s Marilyn Monroe reading Ulysses:

All, (Marilyn, too, I bet!) reflect on the philosophical struggle that comprises ‘moral ambiguity”.

They write and, in doing so, perhaps they answer the question I pose.

As to what I call ‘moral ambiguity’, here’s some help from critics who argue the modernist writer moved inward and away from society.

Here I go with some research (bear with me):

The critic Peter Faulkner argues that “modernist writers fail to see man socially and historically, and so make his alienation, which is a social process, into an absolute.”[ii]

The critic Randall Stevenson argues, “Once narrative places ‘everything in the mind’, a sense of significance can be restored to individuals: it becomes once again possible to consider ‘what a terrific thing a person is’—regardless of how diminished … their actual lives in the modern industrial world may be.”[iii]

The critic Stephen Spender starkly expresses the issue: “In the works of the most characteristically modern writers contemporary civilization was represented as chaotic, decadent, on the point of collapse, anarchic, absurd, the desert of non-values.”[iv]

I don’t agree with Spender’s view as it relates to Woolf and Joyce, but I think he’s right about where Kafka leads us. And Kafka, most certainly of the three novelists was an adherent of Nietzsche.

The critic Gerhard Kurz notes the importance of Nietzsche to Kafka: “The study of Kafka’s relation to Nietzsche was long obstructed by Max Brod’s [friend, biographer and literary executor of Kafka’s body of work] denial of such an influence. The relation first came to light in 1954, when Erich Heller named Nietzsche as Kafka’s ‘intellectual predecessor.’ [Kurz explains that Kafka met Nietzsche through his friend Oskar Pollak.].” Kurz asserts, “Kafka remained faithful to Nietzsche’s thinking until death.”[v]

Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathrustra is referenced three times by Joyce in Ulysses, showing, at the very least, that Joyce had read Nietzsche.

Considering how well-read Woolf was, I find it hard to believe she was unaware of his work.

The dilemma you and I face and that Woolf, Joyce, Kafka address is: How to decide what we ought to do when alone, separated from society, and believe society may not offer a set of shared values that work.

Virginia Woolf in her essay “On Being Ill,” said, “Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. … Here we go alone, and like it better so.”[vi]

In To the Lighthouse, Mrs. Ramsay looks out on the constant stroke of the Lighthouse and says inside her head, “It will end, it will end.” She addresses the question of existence and asks herself, “What did it all mean? To this day she had no notion.” The novel’s middle section, “Time Passes,” separates the action of the novel and all the characters from society. The inexorable power of time and nature rule in “this silence, this indifference, this integrity, the thud of something falling”, and, in this context, three deaths occur in brackets: Mrs. Ramsay, rather suddenly; her daughter Prue Ramsay, in childbirth; her son Andrew, in the war.

In Ulysses, both Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus are exiles. Bloom is an outsider, a Jew, cuckolded by his wife, shunned by others, the object of derision and anti-Semitism. Stephen, recently returned from Paris, is the loner, struggling with refusal to take the sacraments, with his art, with his dissatisfaction with the politics of Ireland. It’s Stephen who says, “That is God. ... A shout in the street.”

K. in The Trial is the most cut off from the world. The novel opens with K. excluded from society by the accusation of guilt. We find no actual events in the novel. The Trial takes place devoid of time or place.

The movement to the self was perhaps inevitable and technique followed: Interior monologue—something I’ll talk about in Write it! How to get started. Click below for the first lesson.

Interior monologue or what came to be known in Joyce’s work as stream of consciousness arose from a philosophic need to move narrative inside the domain of the “self.”

We’ll be talking technique in your work.

Ulysses intimidates readers because it lacks a clear narrative thread—though I argue we always know what day it is and what time it is. Those who dismiss the novel argue fairly, I think, that Joyce purposely impedes a clear linear narrative thread.

I argue that Joyce questions how one finds the narrative of one’s own life.

This question is bleakly explored in Kafka’s The Trial, where the move to the interior is extreme. Kafka doesn’t allow the reader to know for sure we’re inside someone’s consciousness. K.’s seemingly impossible world could be the “real” world.

Nietzche, Kafka, Woolf, Joyce articulated moral ambiguity: The struggle to find meaning in the face of Nietzsche’s “undeceived” morality, a nothingness, if you will.

Remember this and take heart: The very fact that you, the writer, puts pen to paper, demonstrates a longing for a world where moral decisions can be—indeed, perhaps must be—made.

So, together, let’s answer this question: Is art a path away from nihilism?

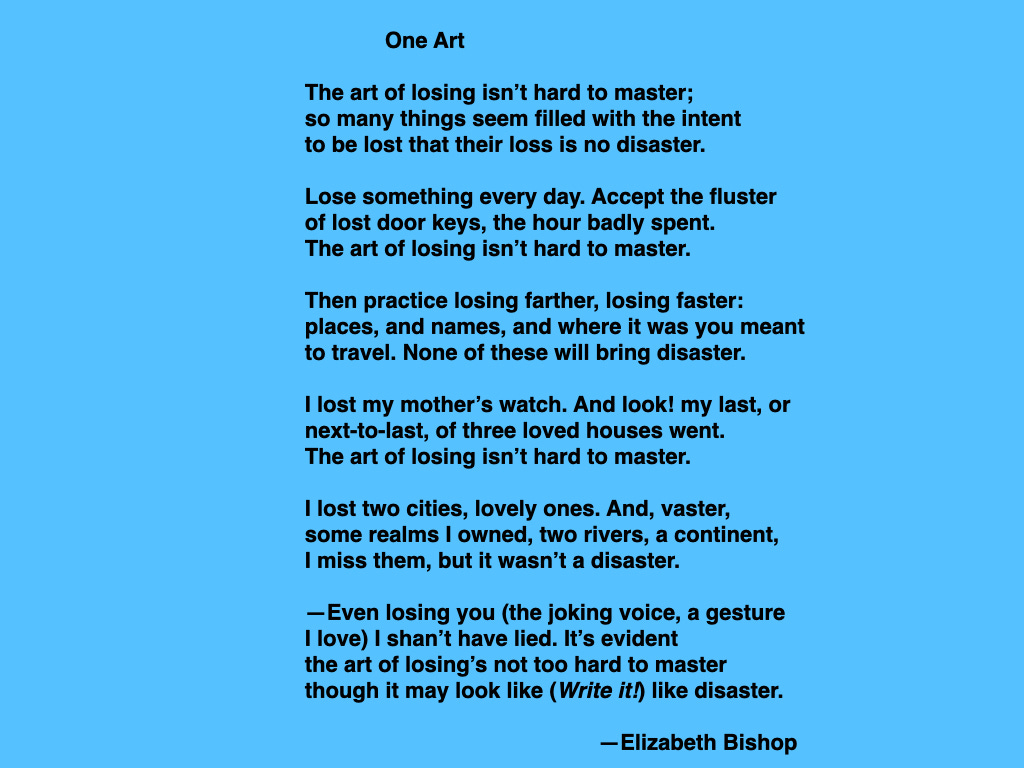

I close with Elizabeth Bishop:

Or

Footnotes and credits:

[i] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Portable Nietzsche, The Gay Science, “The Madman,” ed. and trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: The Penguin Group, paperbound edition, 1976).

[ii] Peter Faulkner, Modernism (London: Methuen & Co Ltd, 1977).

[iii] Randall Stevenson, Modernist Fiction: An Introduction (Hertfordshire, England: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992).

[iv] Stephen Spender, The Struggle of the Modern (California: University of California Press, 1963)

[v] Gerhard Kurz, “Nietzsche, Freud, and Kafka,” trans. Neil Donahue, Reading Kafka, ed. Mark Anderson (New York: Schocken Books Inc., 1989).

[vi] Virginia Woolf, Collected Essays, Volume IV (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1967).

Credits

Photo: Photo Make Art by Enzo Tommasi on Unsplash

Photos: Book covers via Wikipedia

Photo: Marilyn Monroe reading Ulysses courtesy of OpenCulture openculture.com

Another wonderful and insightful article. The immensity of the article's references. Wow. I do believe literature and art can save us. And how writing from the past, triggers thought-provoking questions today—both for ourselves and our characters.