Why Prose Writers Should Read Poetry

Lagniappe #Two for Write it! How to get started

You’ve read this far, so time to go paid for everything on “Only connect …”

In case poetry makes your brain hurt, research in Scotland shows that poetry is good for the brain, that reading and listening to poetry requires greater brain activity than reading prose, that it may help people with age-related memory problems, and children who are dyslexic.

I’m not making this up. (Former is a link.)

Note: Scroll down to bottom for two guest posts and super newsletters—It’ll be worth it.

Reading poetry, in fact, reading any truly good work of fiction or memoir, requires the reader to be deeply attentive, to make quick associations, to be part of what the poet Ed Hirsch has called “a structured reverie” and to willingly suspend disbelief.

All good things for the brain, let alone the heart.

A poem sits on the page in a decidedly different manner than prose. By this very fact, it’s hard to ignore that it is in a “form” meant to be noticed as part of the experience. The reader should, like the poet Auden, ask himself this question when he looks at the shape on the page: “Here is a verbal contraption. How does it work?” (The Dyer’s Hand) That’s the first question Auden asked himself when he read a poem. And it’s a good one.

In some sense, looking at a poem might be compared to looking at a painting. When you stand before a framed painting, you know instinctively that the form of what you are looking at is part and parcel of how it communicates to you. There is no way to separate those two: the form and its communication.

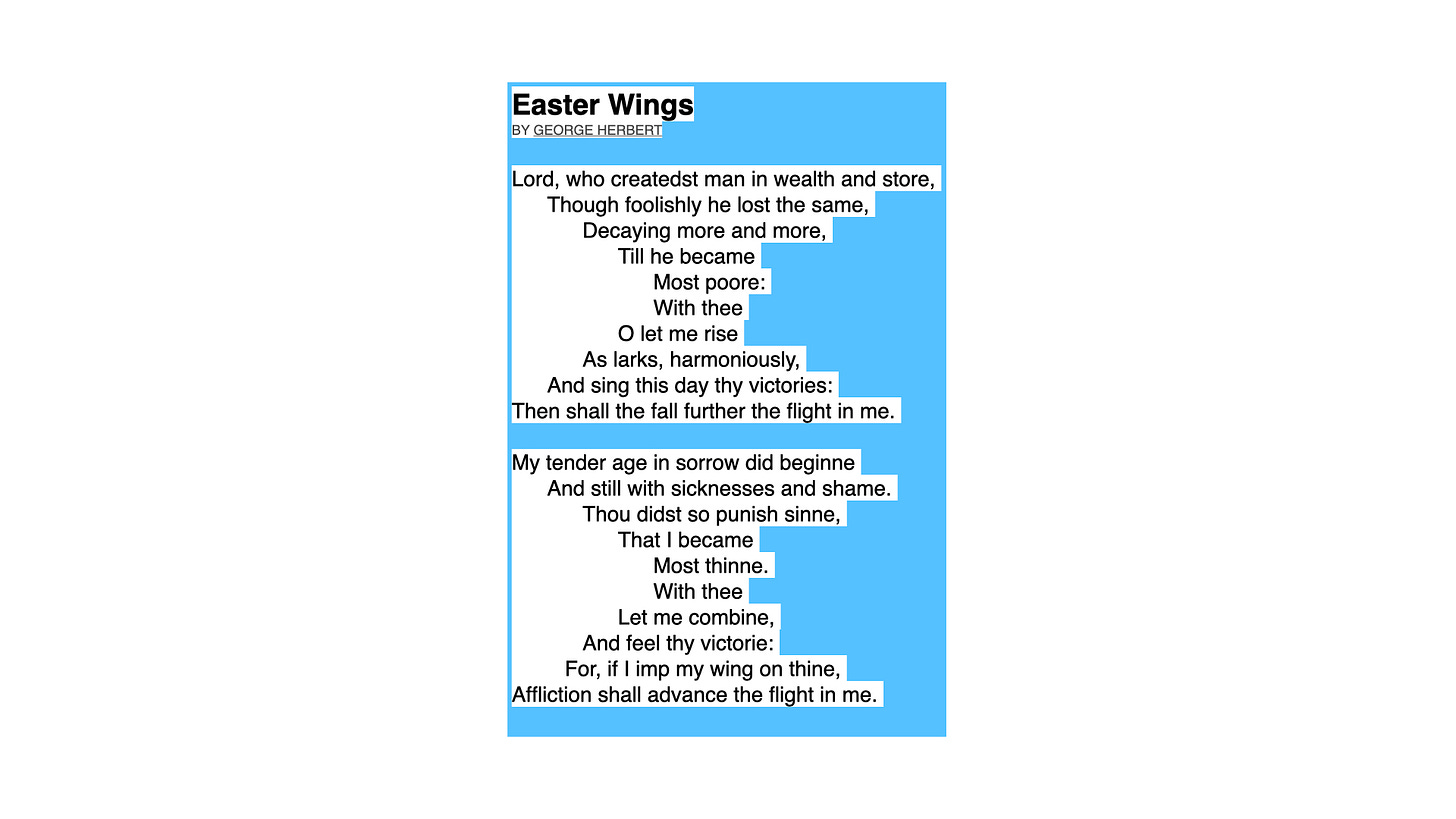

Look at Easter Wings by George Herbert, the master of the conceit or extended metaphor:

Easter Wings by George Herbert

I’m not suggesting that form be this blunt.

If the fact that a poem sits on the page in a form is so obvious, why do I think it’s so important to talk about that? Here are q.s we as writers should ask:

What form will our writing take?

How does form inform meaning?

How is form inseparable from meaning?

All of these are keys to writing both poetry and prose.

Understanding how form operates in poetry will make you a better prose writer. Any poet worth his salt knows that form and meaning must be inseparable for the poem to succeed. This is as true for poetry written in a prescribed form (the sonnet, the villanelle, for example) as it is for free verse.

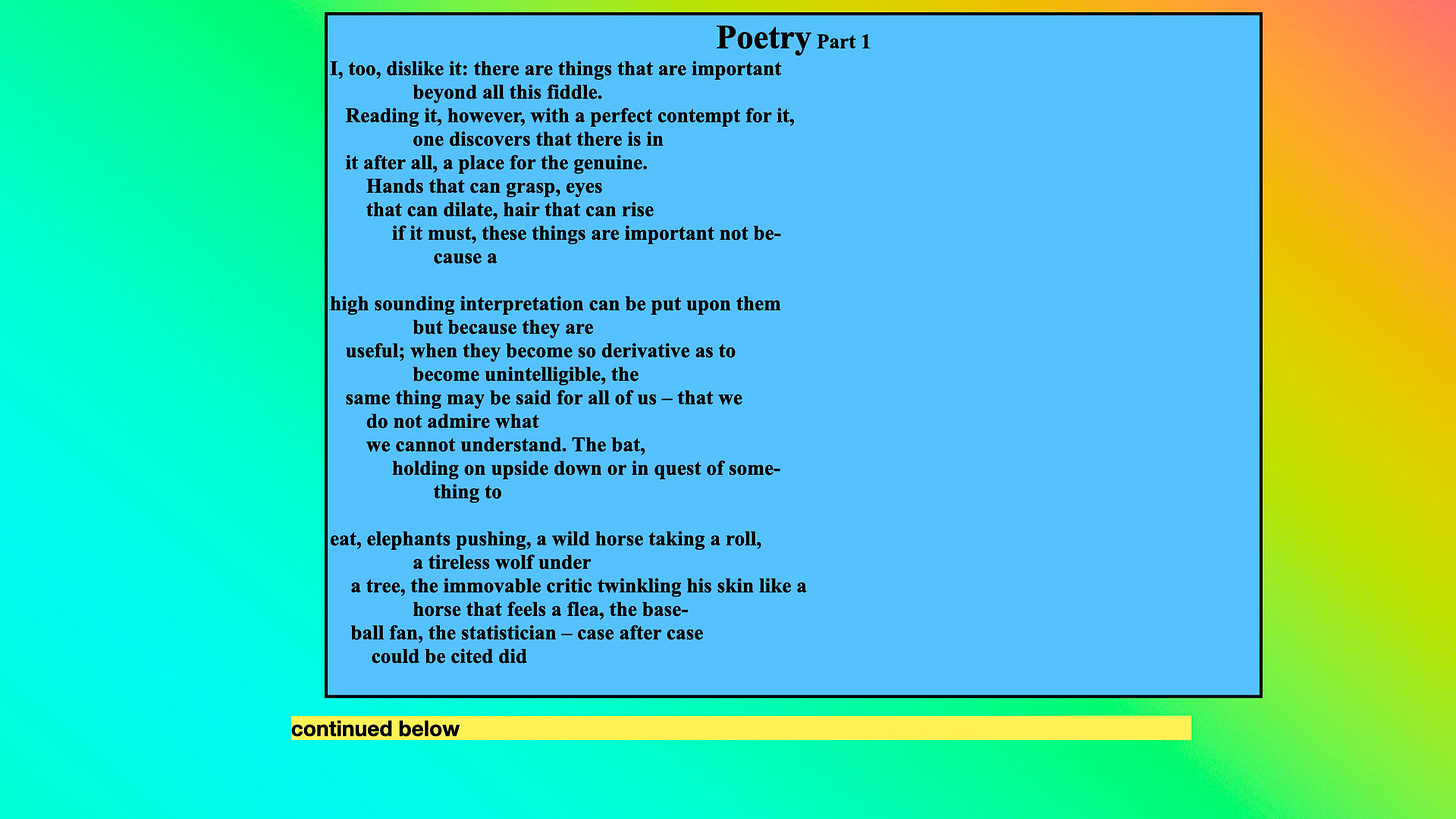

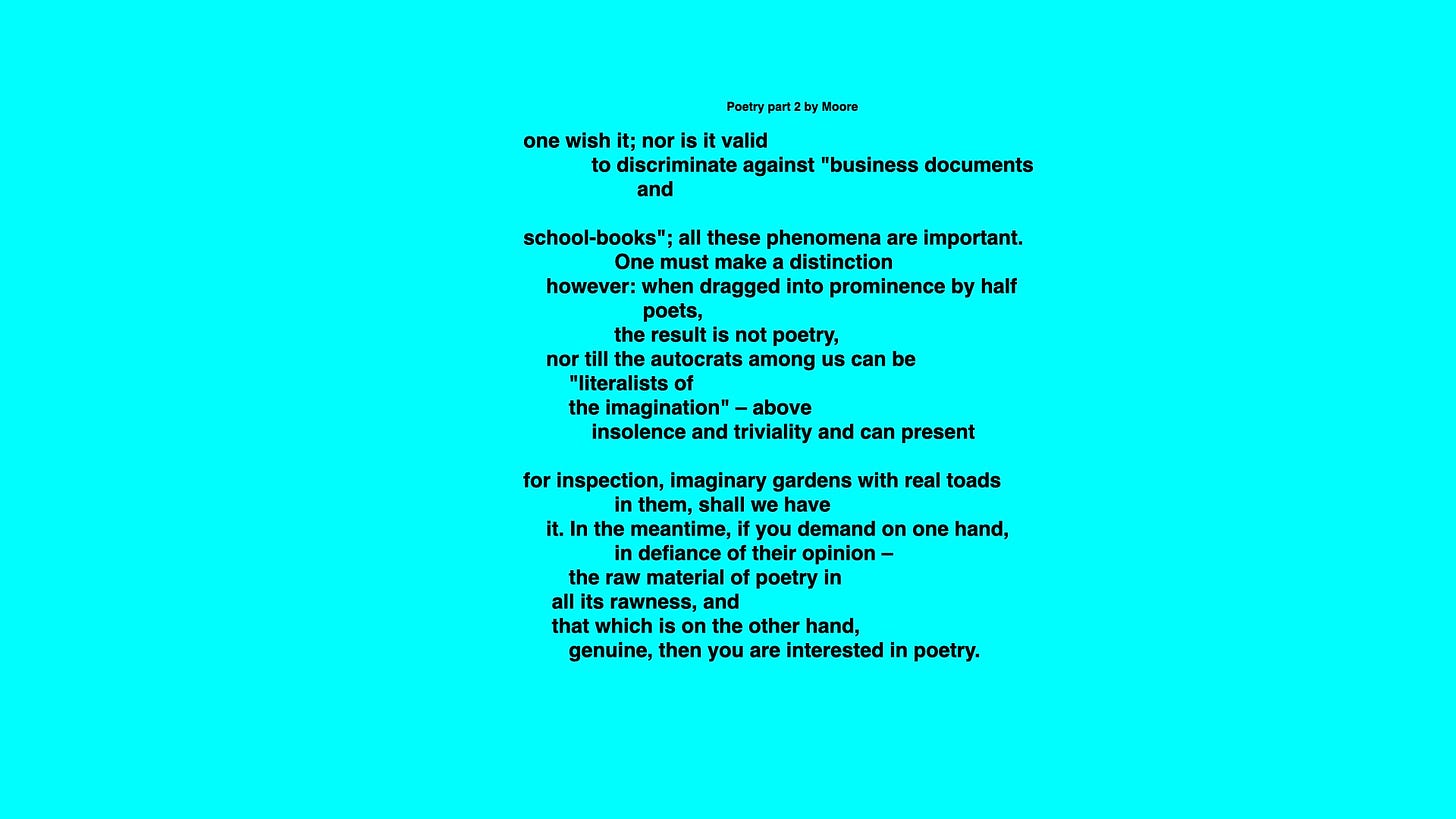

You may still conclude that poetry is more trouble than it’s worth. And you’re not alone. The poet Marianne Moore said about poetry: “I too dislike it. There are things more important beyond all this fiddle.”

Read her poem “Poetry”—a sort of manifesto on what not to do in a poem (in 2 parts below):

Few people buy poetry books. So, how could there be very many people reading it? If you’re among the minority who are, I hereby honor you.

But I also say, “If you’re not, it’s not your fault.” I fault a lot of bad teachers for the state of poetry reading today. They’re on my list of people who should get their just desserts because they had a captive audience and taught how not to read poetry.

They made you hunt for messages and themes. That sort of “hunting” produces readers who won’t go near a poem. It also produces writers of awful poetry.

A better suggestion than “the hunt” for meaning would be Auden’s second question when he read a poem: “What kind of guy inhabits this poem?” That’s a good one to remember. He elaborates: “What is his notion of the good life or the good place? His notion of the Evil one? What does he conceal from the reader? What does he even conceal from himself?" (W.H. Auden, “Making, Know and Judging” from The Dyer’s Hand).

A poem is not very good if the only reason we read it is for the message. Or to put my point more simply, if a prose statement would be better than the poem or at least as good, the poem isn’t very good. Fiction or poetry that is purely idea driven won’t succeed for the reader.

If you read a poem and are uncertain how to sum it up neatly, how to state its so-called theme, you’re not confused, you’re wise. Its layered complexity of meaning is why it’s worth rereading, why it gives pleasure, breaks open in different ways and why it can’t easily be summed up with a “message.” This is not to say that the poem doesn’t have anything to say. It’s to say that a good poem has more than one thing to say—like a good story. I explain this in Lesson 9 of Write it! How to get started:

But how do we go about understanding how the poem is made, let alone attempting to write one? The answer lies partly in understanding something about its “form.” Both the poet and the prose writer will benefit from knowing something about the form of poetry.

You may be thinking at this point, “But what about free verse?” My answer comes from one of its masters, T.S. Eliot, who said “… no verse is free for the man who wants to do a good job. … [A] great deal of bad prose has been written under the name of free verse …. [O]nly a bad poet could welcome free verse as a liberation from form. See Footnote #[2] below. Eliot adds, “Forms have to be broken and remade …”

Perhaps another, more colloquial way to say this might be: Break every rule. But you gotta know the rules to break them.

Poetry is poetry because rhythm drives the poem, is essential to its meaning—even if that rhythm doesn’t follow a prescribed form. You know it’s a poem when you see it , of course, but primarily, you know it’s a poem because you hear its rhythm.

Doing the work of reading and hearing and seeing will make your prose sing.

To close, here’s a poem to hold your heart and inform our study of craft.

Q: How would you describe its form? How does the form help express the effect of the poem? Answer in comments and remember this: Writers do close reads.

A callout here: Two fab newsletters that let me sing: Moviewise guest post on the flick Happy (fine Auden again! and happiness) and the lovely newsletter for writers fictionistas where I sang again about Literary magazines—though Substack may be the new literary magazine (though I have a new lyric essay in Iron Horse Literary Review that I may post here soon.

Or

Credits and footnotes:

Photo: Roses and poem by thought-catalog on unsplash

Photo: Song bird by Jeffrey Hamilton on Unsplash

[1] “imp” in “Easter Wings” is a term from falconry: to mend the damaged wing of a hawk by grafting to it feathers from another bird.

[2] “It [free verse] was a revolt against dead form, and a preparation for new form or for the renewal of the old; it was an insistence upon the inner unity which is unique to every poem, against the outer unity which is typical. The poem comes before the form, in the sense that a form grows out of the attempt of somebody to say something… .” (from Eliot’s essay “The Music of Poetry” in On Poetry and Poets).

Thank you for this marvelous perspective on poetry. I am among those who have thought "poetry makes my brain hurt" ever since my junior high teacher asked us: "And what does the rope signify?" You have blown that apart, with some wonderful help from help from Marianne Moore. Now going to rethink everything...

A fascinating read, Mary - thank you! I have a favourite poem I come back to again and again, and it always helps me to reconsider and sometimes reframe my own work.

Incidentally, W H Auden, whom you’ve quoted here, was my great granny’s cousin. Small world! :D