Note: You can start reading here or anywhere and then go back if you like. Come in the middle? Robert is the narrator who discovers after his wife Lena has died that she had a lover, Isaac. Evan is Isaac’s wife. Robert is on a search for how he lost her: He’s creating the story through memory, invention and a search for the truth and his role in what happened—and by stalking Isaac.

I know about Karen because Isaac and I were in play while Lena died, the hunter and the hunted, each imagining the other. I began to follow him, after that gesture, his hand on her head while she lay in a sickbed, struck down. Here’s what I witnessed on one of my forays: Isaac with another woman—not Evan, not Lena—and so, Karen joins us here.

***

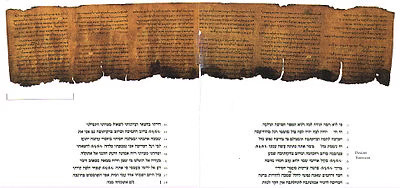

Evan came from the kitchen with the cheese and crackers, bright yellow mustard in a Royal Worcester china ramekin. The large pretzels in a big linen napkin, lay inside a basket. Lena saw how the napkin had colored, darkened with the yellow-brown butter that gave a delicious sheen to the salted pretzels, how Evan had not used paper, more practical, but had chosen this fine napkin for this indulgent snack, the sort of thing Evan would do: make the silly elegant; choose indulgence over practicality. And Lena slipped away: I was zealous for pleasure without pause—from one of the Scroll’s psalms, one not part of the canon and that wouldn’t appear in the exhibit and that kept humming in her head.

Lena, the woman with the songs of the Bible in her purse.

“Isaac, you haven’t gotten out the vodka or the glasses?” Evan said. “Aren’t we going to have a drink?”

He’d behaved oddly and knew it. He’d sat and waited when he should have done what was needed, what he always did when they had guests. If he was to avoid Evan’s questions, he must behave as if he and Evan were entertaining Lena. He got up but didn’t move toward the cabinet near the dining room where the glasses and liquor were kept. But, at least he was standing. He’d do it. “Yes,” he said and stood there, still.

“Let’s get some flowers from the garden, Lena,” Evan suggested. “Isaac, vodka and orange juice? Lena, for you?”

“Flowers, yes. I’ve never seen your gardens.” Lena didn’t answer the question about the drink. She knew Isaac would give her vodka straight up, the way she liked it, the way they took it when they were alone.

The way she took her vodka with me.

She wanted to go into the garden. The house parties had been in the evening when the garden was open for cocktails, but soon obscured by dusk. She wanted to see if Evan had planted roses. What kind? She was sure there’d be roses. Abraham Darbys? Fair Biancas?

They walked through the kitchen, where Lena saw meat in its clear wrapper, poultry of some sort. What would Evan, the gourmet cook, prepare for dinner tonight?

“Come. Isaac’s vegetable garden. He tilled it last weekend.” She walked quickly, past the fresh dirt, past the hammock that hung between two large old oaks, past a round wood table and chairs, where they finish their wine after dinner. “And here’s my garden.” She went to an evergreen of some sort, cut a few branches with an efficient garden tool. She had a canvas bag that held her tools.

The stems were reddish. Lena saw green berries. What are they? Would Evan ask her to stay for dinner? Should she?

“Juniper. Smell,” Evan said. “But the berries won’t be ready until fall. I’ll place a few on the plate with the duck. I have berries I’ve dried. Will you stay? Then you can tell me what’s wrong.”

And so, Evan answered the unasked questions and posed the problem. Lena took a sprig of the offered stem, breathed spice, pine. “So, this is juniper,” she said. With the berries near her nose, she dreamily slipped into another psalm, said to herself in sing-song manner (she didn’t think she’d actually said it), “Coals of broom and woe is me,” and then turned and wandered among Evan’s herbs.

“I thought there was something, just knew it. Oh, I could tell when I saw you here, could see it. But I don’t want to pry. Oh, that’s not so. I do want to know what’s going on. I’m sorry. You don’t have to tell me.”

Goodness. What had she said?

“What do you mean?”

“I think you said— Oh, I don’t know. Maybe I misheard you.”

I am losing it, she thought.

Madness was her fear. She often spoke to me about that. Someone in her father’s family had gone mad. I think it was an aunt or uncle I’d never met. But Lena was far from mad. I was the one who was mad, angry-mad. The uncaring husband. The way I now see I must have seemed to her.

“It’s those berries. They made me think of a psalm—all about hot coals of juniper or broom.”

Deliver me. Did she say that out loud?

She often said that. She’d shrug the words off when she’d say that to me, as if slightly chilled. She would hesitate, take that beat I never knew to take before I spoke.

That’s all Evan needs, she would have thought, me praying. Could she do this, talk with Evan? “I’ve never seen the berry—and broom? That’s what the shrub’s called?”

“I love these berries. I don’t know anything about shrubs. But I guess we could look it up in one of my garden books, see if they’re the same plant. So how’s it going with the exhibit? It opens pretty soon, doesn’t it? You must be under the gun.”

“You know it’s in Chicago.”

“I should remind Jason to go take a look.”

Jason is Isaac and Evan’s oldest child who’d graduated from the University of Chicago. Lena had told me that Isaac said, “He would’ve been better off at one of the Big Ten schools where he’d have spent more time at basketball games worth watching.” Jason ended up selling khaki pants and t-shirts during the day and painting in watercolors and oils at night in his tiny apartment in Hyde Park. Lena told me Isaac had said, “Why, he can’t even move away from campus. I think he’s stuck.”

“I guess you’ve seen the exhibit, Lena. You’d have to, right?”

“At some point I suppose I should. But then I think, why bother? I’ll see it soon enough. I’m not doing that much, and it’s a done deal, pretty much, but I get time to play around with the texts, read them, study them. It’s been good, and I’ve gotten a little obsessed over it all. My mind wanders. Maybe if I went—I don’t know. Probably I don’t have enough to do.”

The truth and a half-truth.

“I’ve got plenty to do,” Evan said, “but most days it all seems pretty useless. People keep coming back. Nobody seems to get better. I’m beginning to think I give more comfort than cure. Not such a bad thing but not what I expected. I feel like an old broom—cleaning up, moving around the messes in people’s heads, never sure if that’s all I’m doing.

I shove one pile into a corner and nothing gets straightened out. Like the old broom I keep in the kitchen pantry. I grab it out of habit and the dust goes flying. I should have thrown it out years ago. But I hang onto it as if it’s some sort of family heirloom because I bought it when we got married. Makes no sense. But these berries. Now they seem to make sense. I spend enough time drying them, buying little bottles I like. Silly stuff. And I can get them in Fresh Fields. That’s me, silly sallying in my valley, dilly dallying.”

Silly not to confront them—in her house late afternoon. Or maybe, with her ingenuous questions, she had.

Lena didn’t think Evan silly, Evan, so good at everything. The garden, full of herbs. Lavender by the fence, a carpet of thyme.

A stand of lacey fennel centered in a plot of grass. A circle of blooming violets around the tall herb, newly planted, not yet full. The garden was fragrant. And then the shrub roses, not the lush, extravagant, pale roses Lena had dreamed of, but small red ones in a border at the edge of the garden.

Evan cut some, along with baby’s breath, poppies, growing to the side of the herbs. And Evan’s extravagance, not in flowers, but in flavorings for food.

She stood in front of Lena ready to go in with her hands full of herbs and flowers. “Has Isaac confided in you? I know something’s wrong.”

“Wrong?”

“Oh, maybe it’s me.”

“No,” said Lena.

“He says I don’t understand his work, that I don’t listen well—something like that, something about the way I listen—what I do all day.”

And here Lena stood, not at some function or in the museum where she could slip away or plead the need to go back to work as she did that day at the Freer. She would want to disappear, fear she’d slip again into the musings that took her away—and now not safely away. She must go, get out of their house, must say something.

“Perhaps it’s that case—the baby’s bones found in the attic? It’s not you, Evan. How could it be you?”

And now she’d done it—brought up the case that had been troubling her. She’d told me about it.

Now I recall how much she talked about it.

But she often talked of Isaac as they worked together in some way I never fully understood. She asked me if I’d read about it in the paper as I keep closer tabs on the Metro section. She told me he’d said, “I’m working with the police. Ain’t that a hoot. Almost as good as that mummified cowboy.” That project got him into her life—that cowboy, that mummy.

The events around that case were a story he liked to tell at social gatherings—at his and Evan’s parties. He was tired of academia, his work at the University of Maryland, wanted his hand back in the action, the way he’d started after college, studying bones to figure out how someone died, helping to solve some seemingly unsolvable case. He liked finding the answers. That case of the cowboy found in an iron coffin over a hundred years old in Tennessee was such an oddity that John, his old school pal had asked him and another colleague, who came all the way from Oklahoma, to come over to the lab at the Museum of Natural History when the coffin arrived for the delicate opening, examination of a virtually mummified corpse. The guy had died with his boots on—straight out of a western movie. It was good science with an angle that made the papers. That’s how the ball got rolling, his decision to take a leave from the college and work for the Smithsonian.

Since then he and Lena had been working one grassy walk away from one another, thrown together now and then on the occasional project for some five years. She’d call to ask a question about DNA analysis of skeletal remains and of the parchment itself for something she was writing for the Scrolls brochure. Access to one another bore the easy mantle of a professional relationship. And they saw each other socially so we’d come to know Evan as well.

Next: Evan — prose 4

Table of Contents

Love,

“Coals of broom and woe is me.” I love the way the broom hovers around the chapter in different ways. Wonderful stuff!

I so want that garden. But wait, there's trouble afoot! Let's get back to it...

Have I mentioned that this shouts "movie"??