In memory of my father who died on June 6, 1999.

For My Father

To Whom It May Concern:

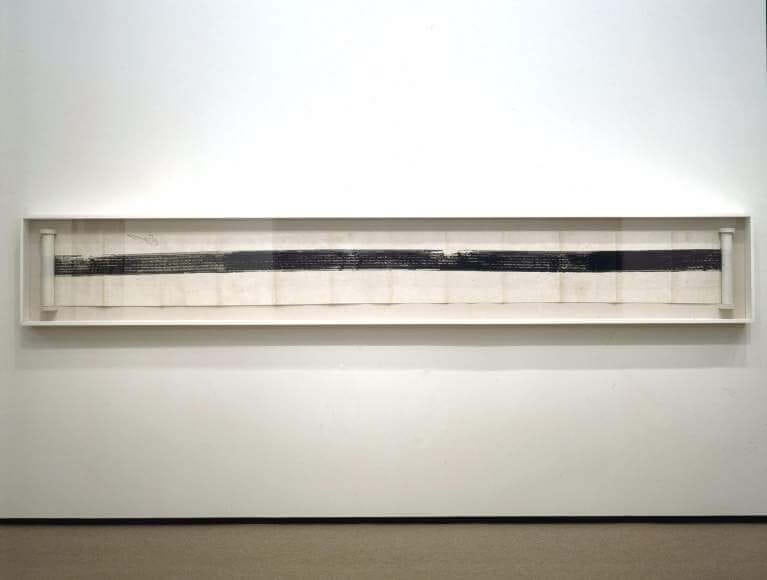

The white paintings came

first; my silent piece

came later.

—John Cage, “On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist and His Work,” Silence, p. 98.

I wrote this in 2008, to hold, to honor, to recall:

Stock market crashed. No noise. Economy in dire straits.

Robert Rauschenberg died on May 12, 2008 at the age of eighty-two. That day I walked over to see his work at the Portrait Gallery near my apartment.

I saved the obit., got caught in the web of memory. My own straits.

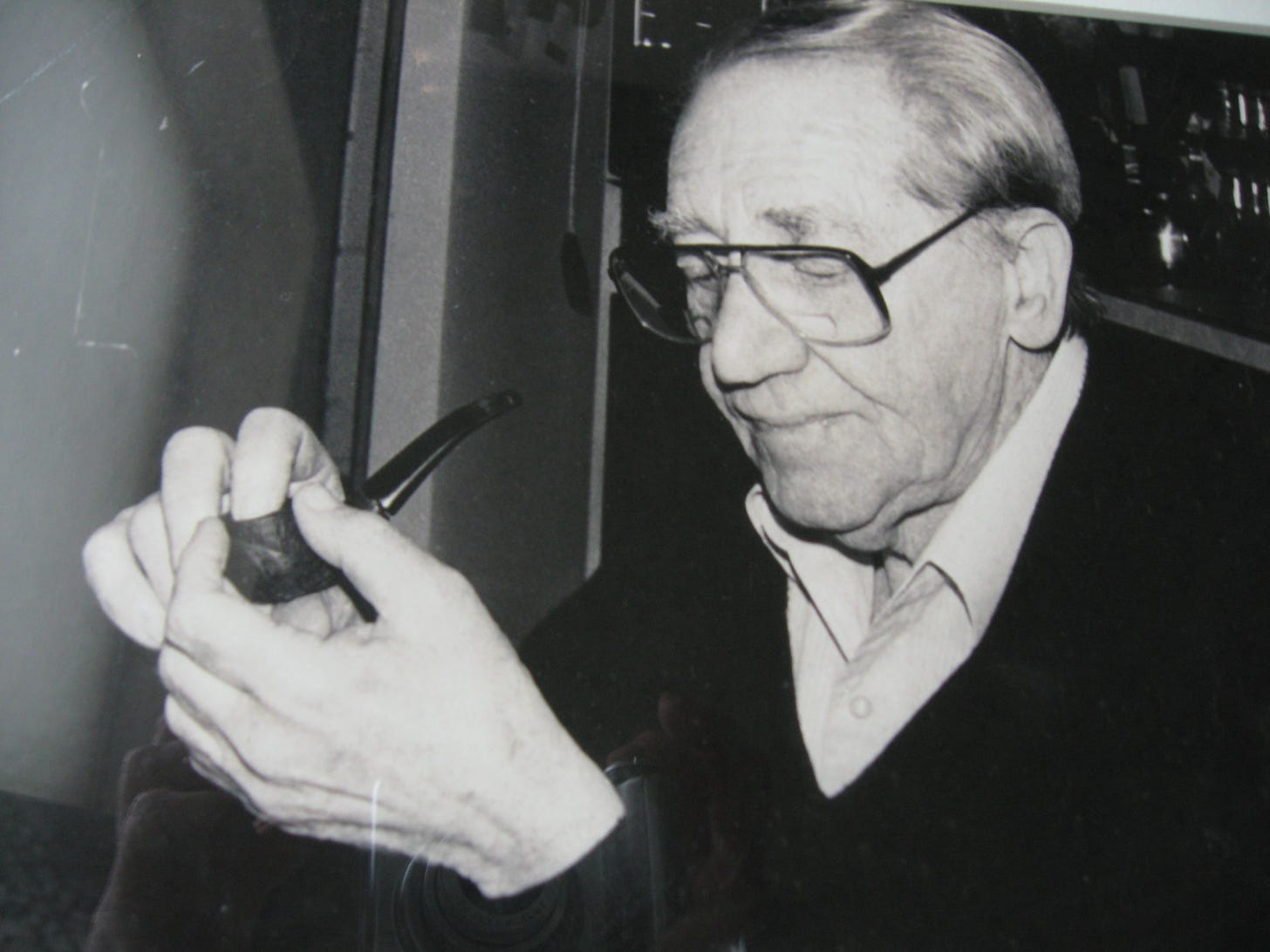

My father’s white shirt, the ribbed, sleeveless undershirt beneath that as a small child I carried with me: “her schmata,” my mother called it. My father’s photo taken by my daughter when she was studying photography in high school, developing her own pictures in Bethesda Chevy Chase High School’s darkroom, hangs on the first wall to my left as I enter my bedroom in the flat where I live and write. He is holding his pipe, one finger tamping down the tobacco, the can of Amphora nearby. The photo is black and white and my memory of him, faded to tone. He, a decade gone this June 6, eighty-four and crippled from Parkinson’s disease and a broken hip when he died.

He comes to me like his home movies, overexposed, so much light that I can barely see him. Rauschenberg-white: my father’s white dress shirt. “I always thought of the white paintings as being not passive but very—well, hypersensitive,” Rauschenberg said.

The schmata shirt beneath the dress shirt.

My 82-year-old father called me in the middle of the night before he died and in the anguish of aging, asked: “What am I here for?”—a despairing cry that expressed the humility of existence and underscored the imperative of continuing to ask the question even as the darkness moves across us. It is the autobiographical tautological question that starts and ends where it begins.

My father took my hand, and said, “There’s an inevitability about the present.”

I understood the way I’d understood when my mother, four years after her stroke, decided not to eat when the new year came, when she took my hand and said “Yitgadal v’yitkadash”—the first two words of the mourner’s Kaddish. It was five years later when my father took my hand one hot day in June.

We’d been sitting in the house with the old round Toastmaster fan blowing at our feet, humming the way old memories did inside my head. We’d been talking about the kind of housing called “assisted living.” “Assisted living,” he said. “Funny term. Either you’re living or you’re not, right?”

I didn’t answer.

“I’m on my way down,” my father said. “I know that. This is just a stopover.”

“Stopover from what to what?”

“Don’t get philosophical on me, kid.”

My father’s eyes were brown like mine. I saw them full of light from the sun that angled through the window. I saw the green and yellow—the colors of my mother’s hazel eyes—there inside the brown. I remembered my dream after my mother died. In a haze of yellow light, my mother in a flowered housedress. I couldn’t tell the color of her hair—pure white when she died. But it must be dark—around her face in finger-placed waves, how it was when I could still fit beneath her arm, lean against her curve of breast. Then an empty chair. An elegant, suited man on the sidewalk. My mother, on the stoop of their row house. Her arm raised high in dance position. No one stands inside her hold. She leans to unheard sound. She turns round. A fox-trot circle. My father threads eight-millimeter film through the projector, on the wheel. A home movie. Overexposed. My mother. Like the whiteness of a leafing tree against night sky.

“Why are you crying?” my father said. “This won’t be the last time you see me.”

“It’s what I do. I cry, easily, often.”

“So do I,” he said. “It’s inherited.”

Hypersensitive.

Note: I’m offering a 50% discount FOREVER to Write it! (all lessons) and (Re)Making Love and the essays on the arts and film if you become a paid subscriber: See the button below and click to see the offer. You won’t be charged and may still choose to subscribe for FREE. You’ll simply see the offer. Decide then. Offer ends August 22. So go ahead, click ⬇️:

Or don’t wanna help me that way and you’re here free? Be a dear soul and consider this:

You’ll also help me if you click below to share this post:

Love,

Mary, I’m not sure how I landed on this today. But I’m stunned by the beauty and intelligence of this piece. May your father’s memory be a blessing. (I’m more and more struck by all the places we have shared, from Baltimore to DC to Mizzou! Be well.)

💙