When I was a child, I put out a candle flame with my fingers. A trick. I thought the blue place in the center was cold. “Is it?” I asked my father. He said, “No,” said something about oxygen—its presence, its absence—“air,” he said. Breath, I think now. I know, of course, that the hottest part of the flame is just above the blue core, that temperatures vary inside the flame. He said, “It does seem impossible, doesn’t it? No burn?” We looked at my fingers. He said, “Consider it a paradox.”\

My father and I are alike in that we pride ourselves on not being driven by our passions—unlike Isaac and Lena. We’re driven by our intellect, our need to know things, our rational powers to sort things out. Also, in my father’s case—and Isaac’s—we’re driven to grow things in orderly rows; I got up at five and farmed with my father as soon as I was big enough; that work, which I got away from as soon as I was old enough, and the gift of the rising sun, which I rarely see anymore, are early memories.

I don’t grow anything anymore; I mow the grass in orderly rows. My father survived the all-too-common small farmer’s demise because he ran the farm with a businessman’s head. He and I are both driven by our need to understand economic markets—in my case, what I do at my computer, for a living—finding order in seeming chaos (not unlike Lena, who read poetry, studied Shakespeare as if he’d give her answers; she quoted when she was upset—one of the things I picked up from her though I’m not as good at it).

The poet Frost (forgive the pun on cold-fire, unintentional), who said, “From what I’ve tasted of desire/ I hold with those who favor fire,” in a masculine rhymed couplet and perfect meter that I find annoying, also said in rhythmic variation that suits my sense of sound, “All is an interminable chain of longing.”

The year before Lena died, she gave me the scores for Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, the “Emperor”; for Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in D Major, the “Titan”; for Schubert’s Piano Quintet in A Major, D667, the “Trout”; and for Stravinsky’s “The Firebird.” She gave me these books with their multiple staffs of notes—“The Firebird” with notes for two piccolos, two flutes, two oboes, an English horn, three clarinets, a bass clarinet, three bassoons, three trombones, a tuba, violins, the piano and many others—when I was no longer playing the old black Steinway baby grand that I hadn’t tuned in over a year.

The piano lay quiet like the word piano but sat there hard, visible, concrete. Like Isaac.

Like Isaac, who leaves his dried-up watercolors in his potting shed, and wants minimalism, wants geometry, the thing that insists on being only itself, I left my piano to sit like a minimalist statement. Like Isaac who had stopped painting, I knew I could never play well enough to satisfy.

When I played the piano, I heard all the possible interpretations of the phrasing, the tones, versus what I was able to produce from the sounding board. My inability to reproduce those interpretations no matter how well I did play accused me.

Lena told me that the revered Rabbi Akiva had twenty-four thousand disciples who studied his teachings and came up with twenty-four thousand interpretations. She found this comforting and would repeat it to counter my certainty when I would assert that I couldn’t play.

I hold the scores of music in my hands, listen to the sounds of the instruments, twenty-eight different ones in “The Firebird,” blending with one another, and I’m able to hear each one in its staff of music on the page. I don’t need to put a CD in my player.

I don’t see the fabulous bird with its plumage of fire. I don’t see the ballerina who goes on point and is lifted in flight. I have heard of but not seen Chagall’s designs for the sets. I have never seen Balanchine’s choreography of this music. I have never been attracted to dance, only to music. In the quiet, the score in my hand, in “The Princesses’ Round: Khorovode,” I hear a lullaby, lean back to let the flutist know he should play his low notes, that the oboe’s haunting tones should enter.

I hear what I conduct.

She understood, knew it happened before I touched the keyboard—that moment before I began while I scanned through the pages of the piece. When I used to play, I played only for her—never in front of anyone else. In return for the gift of the scores—her hand outstretched to me—I didn’t play the piano. I didn’t read the scores in front of her. I didn’t let her see my hands fly through the air, the score in my lap held open by a slide rule.

And now their story—the only way I’ll find my way through.

I begin with a memory: Lena comes home late one evening, cooks a dinner for me from recipes Isaac’s wife Evan has given her. She tells me she’d been to the farm for a drink with Isaac and Evan. To the farm? I knew she liked Evan. I didn’t question this. Now I do.

Yes, this is my version. Call it imagination. Call it revenge. Call it what you like.

I call it discovery.

Forgive the interruptions. I won’t stay out of it.

***

In her office, Lena was held by a phrase of translation: And from beneath the throne came forth streams of fire, from a fragment of Enoch in the Dead Sea Scrolls, a dream vision. She tried to continue working but this vision of the chariot throne, coming like fire, like lightening, the way it kept coming, frightened her.

Lena was working on the exhibit of the Dead Sea Scrolls coming to the Smithsonian, though the exhibit was pretty much set—it was in Chicago. She spent her time considering small changes in the layout that would allow the exhibit to fit into the Sackler Gallery’s set-up where it was to be displayed underground, like the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem where they’re permanently housed, underground, like a cave—the subterranean. The underside of her life, the side she shared with Isaac, her lover, belonged there.

The halls were well-lit, but windowless and, like entering sleep, she entered awake and fell into dreams. At work, she dreamt awake; at home, she dreamt asleep. The Scrolls and the Bible, full of visions and dreams, made her dream more often, more vividly, in color: beryl and sapphire, flame-red and shades of ochre, colors that filled her dreams. Each time she dreamt these colored dreams, awake or asleep, she woke with an ache in her chest. Though disturbed by the dreams because they left her feeling something missing, out of reach, she began to count on them to fill in the blank they created.

While she drifted, day dreamed, I imagine Isaac arrived at her office door. I imagine her looking at a blank wall, him standing, watching her.

Here’s what he’d have done that morning.

Isaac works in a lab in the basement of the Museum of Natural History, across the Mall from the Sackler. He’d have said to himself, “I’m mad or this is a damn dream,” Lena’s words, the end of order. She was on his mind. She was always on his mind.

She is always on my mind.

Maybe he should go home, work in his garden, build the wall for the espaliered apple trees that would border his field of lavender, the trees on the outside of the wall. He’d get out his digging bar and use its round end to pound the stakes he’d use to mark where he would plant the trees. It wasn’t the best tool for the job but its heft had gotten him out of jams, building confusions, when he’d had to pry himself out of a mistake. He’d used his prybar to get the leverage he needed to take out the mistake and then his digging bar for a new hole and he’d realign where he’d begin again. He saw the heavy tool, some twenty or thirty pounds of metal, in his hands, how he would swing it on top of a pole to begin a hole in the hard soil. This made him think of building a house. Maybe he’d build the greenhouse for his wife Evan, the one she’d wanted for so long, maybe the holes would be the first step, his marks for the foundation set firmly with these holes, the way he’d begin.

He knocked on Lena’s open door. “Come on, let’s get out of here. How about a drive somewhere?”

“Where?”

“I don’t know. Out of the traffic, a drive into the country. Didn’t you do that when you were a kid? Go for a drive?”

“We’d do it on summer evenings,” she said. “Drive out for Breyers ice cream. My mother always had butter pecan.”

“What did you have?”

“In those days, mint chocolate chip.”

“So, you want ice cream?” he asked.

“No, coffee.”

“We always have coffee.”

“I can count on that.” She needed someone she could count on.

They took her car because he’d taken the subway to the office, and when they saw a Starbucks, he pulled up to the curb while she went in and bought the steaming cappuccinos they sipped through the plastic covers. He drove to where he wanted to be, his farm.

She would have questioned him, “We’re getting awfully close to the farm.”

“We’ll be alone,” he said, “I don’t want the rigmarole of a hotel. It’s too late in the afternoon for that, anyway.”

Sitting on the loveseat in his house, she would ask because Evan would be home soon, “You trying to get caught?”

“Right, the coffee crime.” He offered his coffee-filled paper cup in the gesture of a toast that she met with hers in a silent clink.

“I’m mad, or dreaming, and you know about me and dreaming.”

“You know you’ve got me saying that now? That quote. You quote when you’re upset.”

“More like misquoting. This probably wasn’t such a good idea, coming here.”

“It’s fine. You’ll be on your way soon.”

“So, we pretend.”

“I’m not pretending. I just wanted to be alone with you. You trying to ruin it?”

“Or forget everything like drinking from a river in hell.”

“Oh yeah, sure. Let’s do that. Quoting again, huh? Never mind. Okay, I’ll play. And what happens when you do that?”

“You forget your life.”

“All of it?”

“It’s like bang, you’re dead.”

“And everything’s gone?”

She nodded. But what she must have been thinking was that he’d somehow managed to forget how she’d loved him, given herself to him, when she’d turned thirty, when they first met, how he’d ended things, didn’t call her anymore. Of course, he was married. She’d known that. He didn’t want to talk about what he referred to as “all that,” and I can hear him saying, “Let’s just call it our stock market correction,” and that was that.

But what did either of them know about financial markets? Zilch.

***

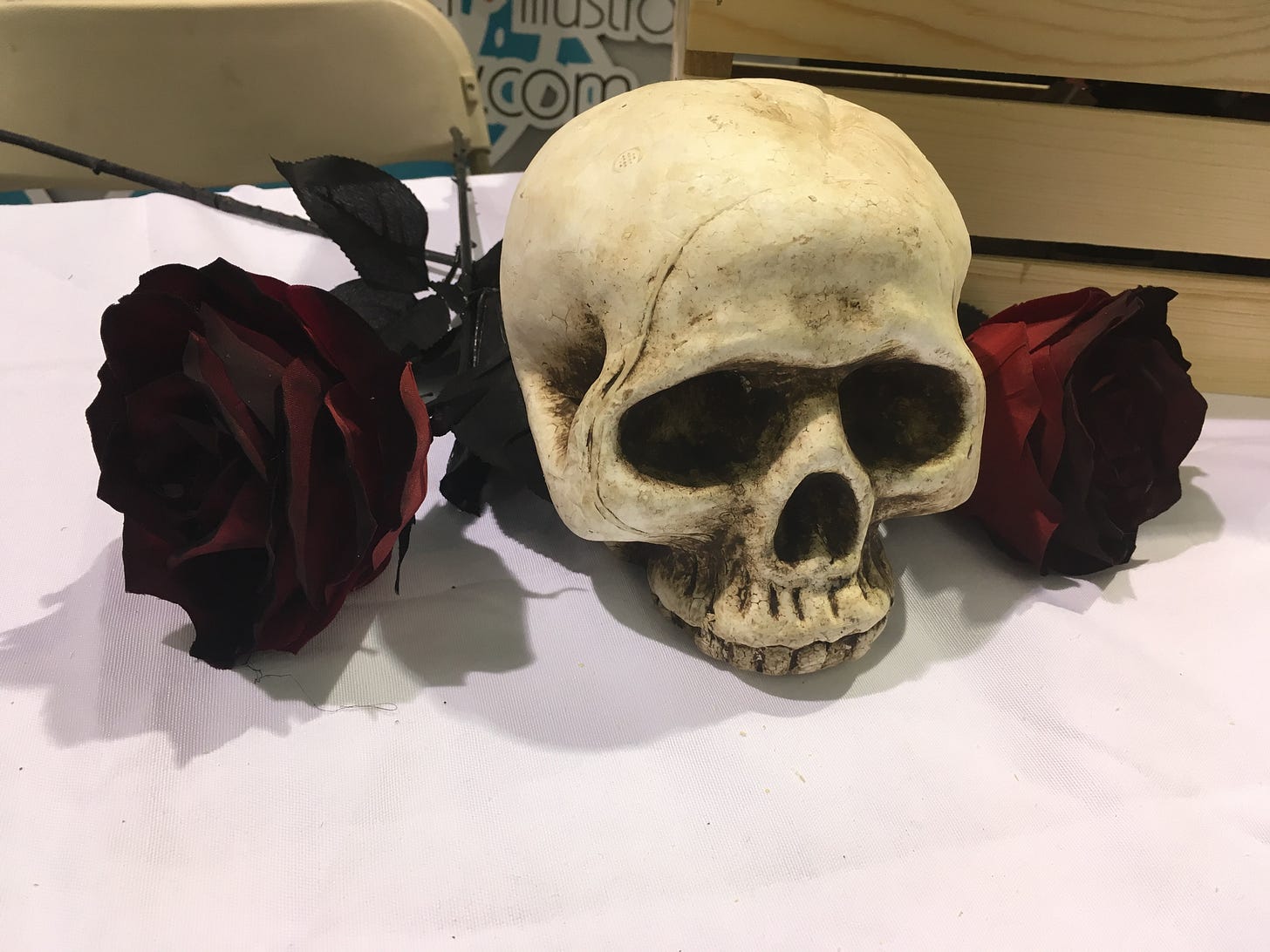

I am like the skull that grins in at the banquet—the only way I can know who I was—because as you must know by now, their story is my story.

“So here’s how the story goes,” she said to Isaac.

“There’s this guy and he gets to this place where nobody’s who they seem, and he wants to forget his past, live for the moment, as they say.”

“You think that’s what I’m trying to do.”

“He’s wishing,” she said. “It’s all about love at first sight if you believe in that. But then it’s a comedy.”

“So the guy gets the girl and everybody goes home happy.” He touched her lower lip. “Here’s a fact: In seventy years, a heart beats two and a half billion times—in my case, more.”

“And, in threescore and ten?”

He laughed, “Are we keeping score?”

***

My heart beats fifty-eight times in a minute, steady, slow. I keep score.

***

She laid her head against his legs, against his crotch, her arms around him. He circled the crown of her head with his hands. This way they comforted one another. They didn’t kiss.

For her the moment of union was the kiss. It must have alarmed her. She wouldn’t have thought of their lovemaking as fucking though they did it, wanted it, needed it. And then the rest: When? How? If? “We must.”

Could she go for months with only the kiss though the kiss quickened the fire? Did this urgency frighten her?

The kiss. What could it mean? That moment when their lips grazed, barely touched, as each took a breath. And then the kiss itself. How could desire become this particular, how could this concrete act of touching mouths be so different from anything else she’d known?—so extraordinary in the reaches of feeling, the sudden rush to the groin, the awareness of the heart beating. Did she feel silly, romantic, sentimental, over the top, like a kid?

They’d both recently turned fifty.

Lena didn’t tell her age to anyone anymore. She would often say, “I know this is trite, straight out of the movies, but I like to say I’m a woman of a certain age.” She liked to say this because she was uncertain about most everything in her life that seemed to matter. And this phrase was a way of expressing that uncertainty, its double meaning, the word certain to say uncertain.

He’d say this sort of thing, “I could close my eyes or turn off the lights and light a candle.”

She’d laugh. “Gimme a break. Romance-novel talk.”

But he knew when she was alone or with me, her husband, that when she was without him, she would replay these words in her head and long for him even when she considered discarding him, when she considered living a sane and good life. She wanted ever so much to be good, though, being of a certain age, she could no longer define that word good.

He said, “You’re really giving me a hard time today. I give up. Here’s what you want to hear. We’re on the brink of disaster.”

He knew that courting her, if what he was doing could be called that, was courting disaster because he knew it was love at first sight. But she’d never buy that and he was lousy on the follow-through—he didn’t think he could ever leave Evan. He said, “I don’t know what I’m talking about.” He decided to talk about what he knew, the potting shed with its metal roof where he stored his garden tools, where Evan started her herbs, that he’d built behind the house. He pulled a screw from his pocket. “Do you know what this is? It’s a sheet-rock screw or dry-wall screw. A self-drilling screw, doesn’t need a pre-drilled hole, even into metal studs.” He said he was considering a greenhouse or perhaps espaliered apple trees, told her how he’d place the stakes near a wall so the warmth of the wall would make the trees grow faster.

She took the screw from his narrow fingers, his nails, clean and pared, his skin dry from his work on his garden, and rolled it in her palm, saved it like a memory, for later—the house they would never live in together, the roof he would never fix for her, for them, the silly gazebo that they both would find frivolous and unnecessary but want anyway out in the rose garden with all the varieties they would choose together, standing hip against hip in the nursery trying to decide which colors would blend with which. Should they go with shades of dusty rose? Remember those old English roses we saw growing in California?

But they hadn’t been to California together. She’d been there with me.

They would decide on ‘Fair Bianca,’ ‘Bredonne,’ ‘English Garden,’ and ‘Abraham Darby.’ And right in the center he would build that foolish gazebo, and they would sit among their roses and drink tea on cool afternoons, wine in the sultry dusk and talk about how they’d chosen just that color from the sunset in that rose with its full head of open petals leaning over the rail. How they’d known the sun would set just that way, how they’d guessed the colors from the sky. They would look up at the gazebo’s roof and remember where he’d had trouble with one ornery sheet rock screw that wouldn’t sit exactly right, how he’d had to take it out again and again.

All the things they would never do.

She placed the odd screw in the zippered pocket of her purse.

In this way, I suppose, she saved all the things she knew they’d never share, things he shared with Evan. Evan, who’s been betrayed like me.

Lena would want to get out of their house. “Isaac, I should go. Evan wouldn’t understand why I was here so early. We shouldn’t have come here. Why did you bring me here? I think you do want to get caught.”

“Oh, sure that’s me, the guy who lives dangerously. Makes me attractive, don’t you think?”

“You know, maybe, maybe not.” She stood up. “Come on, let me go.” He had her hand. She had her car keys out. She nudged him with the keys, “You may like living dangerously, but I don’t.”

“To the extent that we are, we’re safe.”

“Oh, getting philosophical on me, are you?”

“Who me?” he said. “Gimme those keys.”

“No way.”

She understood that he didn’t mean To the extent that we’re about to be caught or choose to live dangerously. She knew what he’d said was code for what he believed and had told her many times: “While nothing is forever, to the extent it can be, we are.” But she’d resisted his reasoning, said, “If nothing is forever, there is no can be, no extenuating circumstances could make that so.” And so she said now, “Then we’re not safe.”

We often spoke in code to one another. For days on end we couldn’t remember the name of the actress in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, a movie we both loved because no one seemed to be who they were in the film, the way neither Lena nor Isaac was who they seemed.

We’d come up with Lee Remick when it was Eva Marie Saint. From then on whenever either one of us couldn’t remember something, the other would say “Lee Remick,” and we’d laugh as code for the problem and the movie we both loved.

***

She jingled her keys at him like a dare, which maybe it was, so he sat down in a mock gesture of defeat. “Me, philosophical? That’s a laugh. My head is like piles and piles of papers that I rummage through. And I like order. I’m accustomed to order.”

“And that’s why you’re with me, I suppose?”

He laughed. “My memory is bad.”

She wanted to believe this was the way he told her he understood how hard it was for her that he’d once rejected her. She said, “You just have selective memory. You choose what to remember. That’s your way of writing your own stories about yourself.”

“And who doesn’t?”

And now he’d made her laugh the way he could when they talked around what couldn’t be said, as if they were so intimate.

***

She was my best friend. I told her things I’d never say to anyone else, couldn’t imagine even saying out loud. I often couldn’t remember what I’d thought versus what I’d told her. In truth, talking with Lena was like having her inside my head.

***

“Maybe I made you up,” she said. “Maybe you’re not real.”

“Me? I’m totally real. Here, poke me, you’ll see. But put those keys away first.”

She dropped the keys into her purse, sat down and gave him a nudge with her elbow. “Yeah, well, maybe I have a trust problem?”

“You think?” He always said this when she asked him something she knew was so, his way of pointing out the obvious with ease. And this had become a joke between them.

They must have had private jokes.

She laughed. “Okay, okay, so maybe I do, but I don’t want to.”

The absence of trust was a fact of their connection.

“I don’t think I’m totally trustworthy,” he said. “Not by nature, but perhaps due to circumstances.”

On the brink of disaster, about to be caught, he kissed her.

She leaned into his shoulder, put her head in that curve below his neck and breathed in the sea-water smell of him—the salty taste when her tongue skimmed his neck and her nose burrowed in his skin—there in the place where she laid her head, there, she took him in, an almost airless breath of him. It was like the sea—when she’d sat at the edge, her feet in the water, her hands in wet sand, her back leaning away from the breezes off the ocean that swirled over her, her face towards the sun, when she’d been overcome by the salt in her open mouth and the briny air in her nose. His scent that aroused her with his presence. Sea and sand and his neck.

He wrapped her in his arms and for this moment she was safe and sure when the key to the front door turned. They heard the pins inside the lock tumble. A familiar sound, merely a click, but they thought, almost as if their minds were one, that they heard the separate mechanisms of the lock moving, tumbling like thunder.

This is the sound of fear, thought Lena.

Isaac knew, This is the sound of the inevitable.△

Next: Me and Lena, Chapter 4

If you want the prose, in section on your phone, The Lovers, prose 2, The Lovers, prose 3, The Lovers, prose 4 , The Lovers, prose 5, The Lovers, prose 6, The Lovers, prose 7

Table of Contents

Love,

I love the way you draw the stark differences between the two personality types and then weave them back together.

Oh, my! Love it. The juxtaposition of fear and the inevitable captured as (a) sound(s) is such a good ending. ♥️🎶