Note: Update: Robert faces Lena’s death …

You can start reading here or anywhere, then go back. See Table of Contents. Come in the middle? Robert is the narrator who discovers after his wife Lena has died that she had a lover, Isaac. Evan is Isaac’s wife. Robert is on a search for how he lost Lena: He’s creating the story through memory, invention and a search for the truth and his role in what happened—and by stalking Isaac.

Lena

With Lena’s death imminent, I moved my piano to the Jason, had it tuned again. I began to play it with my window open while she lay with the Brompton’s Cocktail taking over.

With the exhibit now open at the Smithsonian, with Lena unable to attend—at the opening gala, invitation only, there they were: Evan and Isaac together. So, she did decide to go. I stood at the doorway and then went down to Lena’s office.

Again I looked.

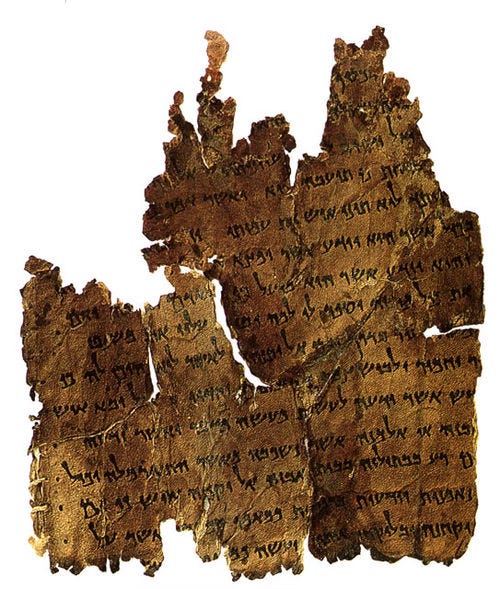

There on the slanted table on top of the maps lay the open book and next to it on a yellow sheet in her handwriting she had copied the psalm I read on the open book page. The psalm appeared on the right in Greek with the title “LXX (apud Swete)” and next to it in the Hebrew with the title “Q”. I had no idea what either meant. I read the psalm in English that she’d copied onto the yellow lined paper with its red margin. There were two English translations in the open book on the right side of the center seam: one of the Greek and one of the Hebrew. The book was hardbound and stitched and although not one of the signature pages, the page where the stitching can be seen, the book had lain open to this page for so long that the stitching appeared as it if were a signature seam. I examined the book this closely because she’d copied the English translation of the Hebrew. When I lifted the paper, I saw that she’d copied it over and over again, page after page of the same psalm, same translation.

I turned back and read the scholar J.A. Sanders’ explanation of the translations. Lena had taken a yellow highlighter to some of the passage: “This is to observe, I suppose, that those in antiquity who appended it [the psalm] to Sirach had fairly good reason to do so: the setting of the canticle fits very well that of a ‘sung’ confession by a Wisdom teacher who exhorts his disciples ‘to go and do likewise.’ ” And later down the page, “The poem is an alphabetical acrostic (each verse begins with the sequential letters of the Hebrew alphabet), and its stichotic arrangement is, therefore, easily established.”

Puzzles. She had always loved puzzles and games and word play.

Sanders discusses the differences in the texts of the same psalm in Greek and Hebrew and the translations of each. I quote in full what Lena highlighted here with her ellipses (what she chose not to highlight) because it was with this that I began and in some sense it is with this that I will end: “…Greek verse 13b adds a note of piety totally lacking in the Hebrew verse 2a; the Greek is highly pious while the Hebrew begins to border on the erotic. … Even the medieval Hebrew text reflects the difference noted between the Qumran text and the Greek, right up, that is, until what we may now call verse 13 (Hebrew letter mem) of the medieval Hebrew text, which is itself erotic enough: ‘My bowels are astir like a firepot for her, to gaze upon her, that may own her, a pleasant possession.’ But that sentence is in the medieval text of the canticle already known by scholars for sixty-five years.”

Sanders has translated from the Hebrew lines 1 through 11, and this is what Lena had copied onto her yellow pad. I took the yellow-lined pad with all its pages in her script of the psalm and the book, placed the pad inside the book and returned to the room in Gershon’s house where she lay.

“I found this on your desk.”

“Did you go through the exhibit?”

“No. Isaac and Evan were there. I’ll go back another time.”

“Isaac and Evan,” she repeated.

“I went instead to your office. On top of the maps and brochures was this book and this, in your handwriting. I decided you might want it.”

She said, “Remember when we met?”

The day her umbrella popped open, hit me in the face. “Yes, on the mall, not far from your office. The Library of Congress, right? I’ve never actually been in there. I never made it past the door. Did you know that? But, yes, you and your umbrella.”

Since we married, I have often walked toward the mall because that was where Lena was. I think I will always walk toward her.

She said, “When we met. It was a long time ago and then it wasn’t. I know you don’t understand and if you do, well then… Anyway the psalm is for Evan. But give the psalm to Isaac. Tell him what I’ve told you, that it’s for Evan.”

“Will he understand?”

“I don’t know. Extenuating circumstances could make it so.”

Her widow’s peak was visible as she lay on the pillow. The delicate rise of her forehead was accented by a v line of hair that rose to loopy curls around her head, waves of hair that slid away from her face and onto the pillow as if she lay at sea, her hair in the water. “You look like you’re floating, the way you looked in Anguilla when you’d go out on one of those banana peel rafts.”

“When we met you were wearing that overcoat, the gray tweed. I love that coat and you wore black trousers, the ones you always wear. I was wearing a skirt and pale sheer stockings that had gotten splattered from walking in the rain. I couldn’t see the splatters but I noticed later that the backs of my legs were dirty and thought that’s what you’d seen when I walked away.”

Lena was losing her hair. It had fallen out in clumps. She had not lost all of it and her dark hair was so thick it could cover the bald spots. Her hair had not fallen out because of chemo. She was too late, too far gone for the treatment. Her bald spots could only be seen when she lifted her heavy hair that she’d let grow since she’d become ill. She said she had sympathetic baldness. “Like you,” she told me. “ I become like you.” The loss of hair was caused by a perhaps related illness called alopecia, in her case, she said, “caused by my own troubled mind. I have had dreams, chariots on fire when I sleep, when I wake.” I told her it was the Brompton’s Cocktail. But she said, “No,” that the dreams were present, the fires in the sky, the sapphire glass mountains that she traveled over, all were present before the illness and they were still with her and she must ride them out because of what’s missing. I said, “Your breast.” She said, “Yes, but then that would make me prescient and I’m not.”

She was dying with a certain willfulness. She lay down, not just from the pain, and not solely from exhaustion.

I had the flu when I was around forty, old enough to know that I could die, vomiting, diarrhea, aches, chills, fevers that devastated my body and made me think about dying. In the midst of this sickness, I wished I were dead in some sense because I wished for release. But I never wanted to die. I wanted to get better and I fought to get better. I sipped ginger ale and chicken broth because I knew that I shouldn’t get dehydrated. I made the conscious efforts to get well even as I knew the illness would have to run its course.

What I saw in Lena was decidedly different, and each day its decided difference became more clear to me. She didn’t fight back. She gave in to the cancer. “You believe in it.”

“In what?”

“In the cancer.”

“I believe I have it, if that’s what you mean?” And she laughed. “Yeah, Robert, I have it.”

“That’s not what I mean.”

“What then?”

“You believe in it. You’re not fighting it.”

“Are you accusing me?”

“I don’t want to lose you even if we both know your death is inevitable.”

“My dear,” she said with the irony one uses when stating the obvious, “everyone’s death is inevitable.”

“You’re evading me.”

“I don’t mean to.”

“Why do you believe in it?”

“Let’s hypothesize that what you say is so. I don’t accept your assertion, but I am too tired to deny it. So let’s say it’s so. It’s not that I want to leave you.”

“But that’s what you’re doing.”

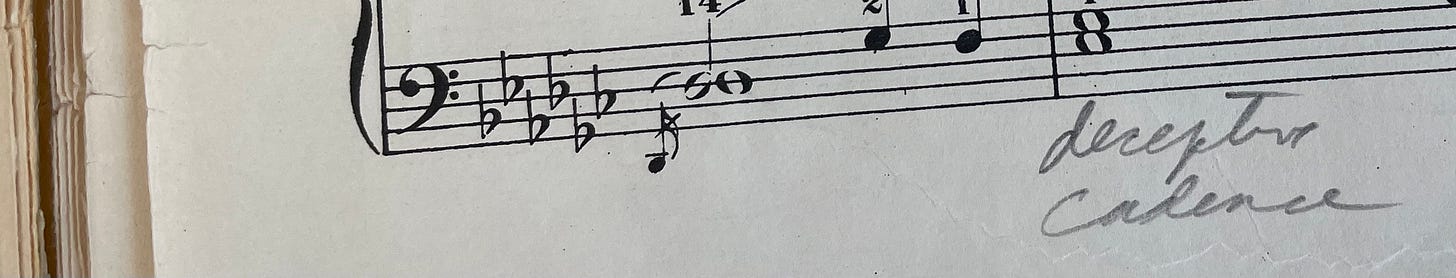

I played Schubert’s Opus 90, No. 3 in G Flat. I played it from the old yellow Schirmer’s Library Classics, Four Impromptus book that my mother had bought me. My name in her script in pencil is still on the cover as if I were just another of her many students: R. Berenson. A note in ink on the front says Andante Mosso, G with the flat mark in her handwriting and on the table of contents a note that says “prelude” next to number 3. She was planning to play it for church, prelude to the service. On the front cover she’d noted the place in her tape recorder where she listened to it: 1026-125. She had written above in pencil on page twenty-one of the book whose pages have all come apart: 9/10 minutes. Rubenstein plays this piece in about six and a quarter minutes. She used to tell me, “If you’re having trouble, slow down and she took her own advice.”

Mosso means literally “motion” and I want Lena to move, to be moved, to get up, to come home even though I no longer live at home. I want her to hear my playing and to know that I am playing. I don’t know if she can hear the piano from her room. It’s the melody that would move her and the melody is exceedingly simple. Any child could play it, but the melody rings only if all the other keys are struck well and swiftly. It’s these complicated patterns that make you wonder how it’s done, think there’s more going on than two hands could possibly do, when you hear Horowitz or Rubenstein do it. When I played it as a boy at the piano on the wall of the dining room, from the kitchen my mother would say, “Now I can hear the melody,” as I tried to get those eighth notes rolling properly, playing up and down the chords, repeatedly, taking the chords and breaking them into their parts, fluidly and separately. Success at this gives the piece its complexity, assures that the rapid notes don’t overwhelm the melody, that both are heard as separate and integrated strands.

I would leave Lena and open my window, begin the piece, roll the eighth notes in my right hand and left, lightly letting the whole notes ring above them with my right just as they sit above them on the staff, try ever so hard to play the whole notes and half notes and quarter notes in the right hand with that ringing, bell-like tone my mother hoped for. And yet I couldn’t complete the piece. Each time I came to the penultimate page, page twenty-seven, there would be my mother’s words on the third staff down the page where the quarter notes are marked cresc. and where below the c whole note that is held for a two-quarter count followed by the d-flat, held for one-quarter, are her words in pencil that refer to the eighth notes in the right hand, deceptive cadence, and my hands would not move forward.△

Table of Contents

Coming next: Chapter 38: “Isaac and Lena”

Only Connect, all sections, and this serial novel come from my heart and soul—and ten years of research. I know the saying ‘time is money’: I couldn’t help but pursue this story. If you have already gone paid, my heart goes out to you with my thanks.

Love,

"She was dying with a certain willfulness. She lay down, not just from the pain, and not solely from exhaustion." I found this very moving, Mary. It subtly suggests a tender egotism on the part of both the observer and the observed.

Ah, "deceptive cadence" -- in music and in life. I love how you so deftly let music repeatedly illuminate the story. This particular Schubert piece seems so perfectly apt.