How to read nonfiction articles, books (not fiction or memoir) and newspapers more efficiently

There’s so much to read these days, that a leisurely stroll through thousands of words is no longer feasible. At least, not if you’re going to keep on top of all the developments that emerge every day. However, simply reading quickly is not necessarily the answer either. Believe it or not, a reading speed of 800 words per minute with a comprehension of around 70% (expressed as 800/70) is perfectly feasible. But the skill lies more in reading efficiently than in just trying to read faster.

When it comes to reading, most people approach the material in the same way they approach a packet of cornflakes. In an age of information overload, that just isn’t good enough. You have a job to do: not only to keep up-to-date for your own sake, but to do so in order to keep your readers or colleagues or boss informed. How are you going to do it?

If the material is well-structured -- in other words, if the person writing it was more concerned with making sure you could get the gist quickly than with his or her own ego -- efficient reading should be as easy as falling off a log. But even if the writer spent more time thinking of flowery descriptions than worrying about your need to get stuff done, you can still save time by reading it properly.

Here's what you do:

Don't Even Open The Document

That's right: just keep it closed, and spend 5 minutes thinking about what you're looking for, and what you think the document might contain in relation to that. Sounds like a waste of time, right? But it isn’t, because what you're doing is setting up some mental hooks on which to hang ideas as they come up from the material, or from your interaction with the material.

Read The Table Of Contents…

… if there is one, as that will help you get a feel for what the document contains. Well, with any luck: if the author has used totally unhelpful section or chapter headings, like "All's well that ends well", you won't have much joy.

Always Start At The End

Well, at the summary, to be more precise. That sometimes comes at the beginning, in the form of an Executive Summary. Read it first, because you'll be able to cut to the chase without all the intervening argument. Like the man said: Just gimme the facts, ma'am.

Read Even More

If you still don't have what you need, well, you're going to have to read more of it. Start by reading the section headings, and then the first and last paragraphs in each section. The first one should say what is going to be covered. If the material has been thought through by the writer, the final paragraph will summarise what's just been covered. It’s a bit like the old definition of teaching:

First I tells ‘em what I’m going to tell ‘em.

Then I tells ‘em.

Then I tells ‘em what I’ve told ‘em.

Read Still More

Still not enough? OK, start again, but this time read the first sentences in each paragraph too.

The Big Picture

I know this sounds very bitty and boring, and if you’re a really fast reader it could even take longer to read this way than just straightforwardly from start to finish. But the emphasis is on efficiency: how to read in such a way that you extract the most important information for your needs as quickly as possible.

Read The Tags

Good website articles and blogs should help in two other ways: firstly, they ought to be short; secondly, they should be tagged -- and the tags should give you a good idea of what the piece is about. Unfortunately, Substack doesn’t make enough use of tags, but the section an article appears in, or its subheading, should be enough to help you mentally prepare for the article to come.

Faster Reading

Efficient reading isn't the same as speed reading, but you can always do some things to help you read faster:

How Much Detail?

Ask yourself if you really need all the detail. If the answer is "no", then you can skim-read the document. A good way of doing this is to train yourself to look out for certain "signpost" words -- and then ignore the rest of the sentence.

For example, "for instance" is an obvious kind of signpost: it tells you that there is an example coming up. Duh. Well, if you already get the point, or you don't need the detail, why waste time reading an example?

Another signpost word is "Moreover": that is often used to embellish a point, and whilst it isn't the same as an example, if you're in a real hurry you might want to skip it. At least for now.

Take In More Words At A Time

Another thing you can do is to read more words at once. You can train yourself to do this, and there is software that can help you. I tried one out a few years ago, but it seems to have disappeared now. No problem, because there are lots of others, as a quick search will tell you.

The one I tried tested your reading speed and comprehension, and trained you to see more words at once. The reading/comprehension test was a little artificial to be honest: in a real context, you would probably have some familiarity with the subject matter, hopefully some interest in it, and almost certainly some forewarning of it. As for the section that trained you to read more words at once, I'm not sure how permanent the results are, but there's nothing to be lost by trying it out.

I have tried apps that purport to help you to read faster by flashing up each word on the screen in rapid succession. I’d be happy for someone to tell me I’m wrong, but it seems to me to be a rather inefficient approach, because you’re still reading one word at a time. Until the next word comes along, you may not be sure what the context is. By the time you’ve worked that out, the original word is long gone!

A note on reading news articles in newspapers

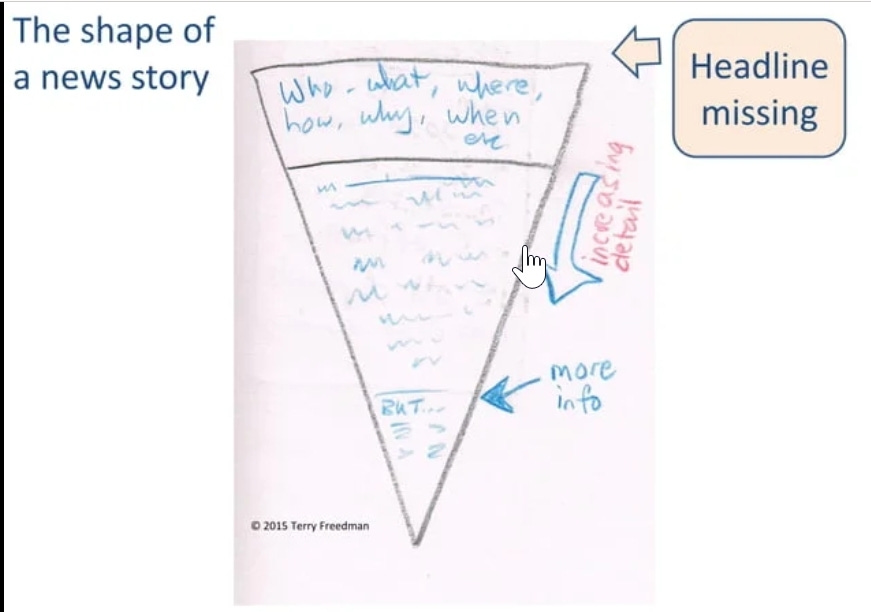

If you wish to be keep abreast of current affairs and you still like to get your news (or some of it at least) from newspapers, you can easily do so by reading just the first paragraph of news articles – if the news articles are structured in the traditional way of what is called an inverted pyramid.

All of the essential information is right there in the first paragraph: what, where, who and so on. For example, consider this start of a news story:

Elsie Jones was walking her dog on Meads Road yesterday when she narrowly avoided being run over when a motorcyclist lost control because of a burst tyre.

We know who (Elsie Jones), where (Meads Road), what (nearly run over) and why (burst tyre).

We should note that not all newspaper articles are in this format. Feature articles, and many news articles in the USA, use one of the variations of what is called burying the lead, or a drop paragraph. These lead readers in more slowly rather than hitting them with all the information at once.

For example:

If your medication is still in date it should be perfectly safe to take, right? Wrong – as Elsie Jones found to her cost….

Another example:

I meet Elsie Jones in a Starbucks in downtown Mayfair. I’ve never met her before, but as soon as I see a figure shimmering towards me in a bright blue dress…

A word of caution: headlines, at least in the UK, tend to be written by sub-editors who may be aiming for a humorous effect or to give a political slant.

An example of a humorous headline would be:

New railway project hits the buffers as money runs out.

An example of a political slant might be:

Bosses cave in to demand for wage increase.

Does the headline matter? Yes! An article in the New Yorker reported research which showed that the headline not only frames the way we approach the article, but even what we remember from reading it[1].

Concluding Remarks

If you’re a writer, then you make life a lot easier for readers by structuring your article or nonfiction book with headings, because these break up the text and make it easier to read. The headings should also mean something obvious, which may mean ditching some clever word play or nice phraseology. For example, one book I perused in a bookshop had chapter headings like “All that glistens…”; “Well I never”, and other completely unhelpful expressions. Equally useless are chapter headings called Chapter 1, Chapter 2 etc.

As a reader, even if the article has not been structured in a way that makes it easy to read efficiently, probably the single most important thing you can do is write down a list of questions or things you expect or hope to see before you even start reading. Another way of thinking about it is that you want to be an active reader, not a passive one. You’ll get a lot more out of the text, and if you write about it afterwards, perhaps in a book review, your account will almost certainly be more incisive as a result.

I hope you enjoyed reading this and found it useful. And do check out Terry’s newsletter Eclecticism.

Next: back to fiction and memoir—and the risks, possible invasions in our conversation about John Bayley’s Elegy for Iris.

For an essay on “Moral Ambiguity” and the continuing collaboration with others digging deep on the arts, and where I also write, go to innerlifecollaborative.substack.com.

Love,

SUCH a valuable post! Those 'mental hooks' are so important, aren't they? We all have certain words that leap out at us anyway, such as our own name, or a location, or something pertaining to our favourite hobby or favourite subject matter - but I'd never thought of thinking ahead to what I'm hoping to discover in a text that I'm about to read. Setting up those 'mental hooks' you speak of would do exactly that job!

I'm certainly going to be working on my reading technique now! I get very, very bogged down in reading, feeling that if I've committed to read something I am obliged to read it really really properly. In fact I don't NEED to go to that level in everything I'm reading! Reading this post has been such a relief in that respect - it has opened my eyes WIDE, Terry and Mary! Thank you. ⭐️

I mostly read fiction but I'm trying to read more nonfiction and I've been struggling to get through all sorts of dense material. Thanks for the useful tips.