She Should Have Known Better: Chapter 3

(ReMaking Love: A serial memoir

Come in the middle? Here’re links to Chapter One, Chapter 2

She Should Have Known Better

I went to Missouri with a long mane of white hair. Hair and its length in women indicate sexual availability. Think about all the women you’ve known who cut their hair after they have a child. Oh sure, they say they cut it because they don’t have time anymore and there’s truth to that assertion: They don’t!

Or think about religious traditions including mine that require hair to be cut off or covered once a woman has married.

I now see that I knew, long before D. left, something in the marriage was amiss because on November 15, 2002, I decided to let my hair grow. I’d worn a buzz cut, a short spiky 'do since I married D. It was wash-and-go, tamed my curly hair and gave me the freedom I thought I needed.

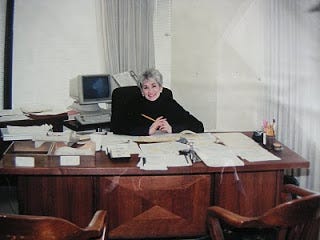

I quit my job where I met D. and married him—see the photo, me pencil in hand—and went back to graduate school in 1996.

I never would have quit that job—or now I realize—cut my hair if I’d thought for a minute that he would leave me. He and I made equal salaries, his a bit more than mine even though I was perhaps more successful at my job than he at his.

I know what you’re thinking: Female emasculates male.

She should have known better.

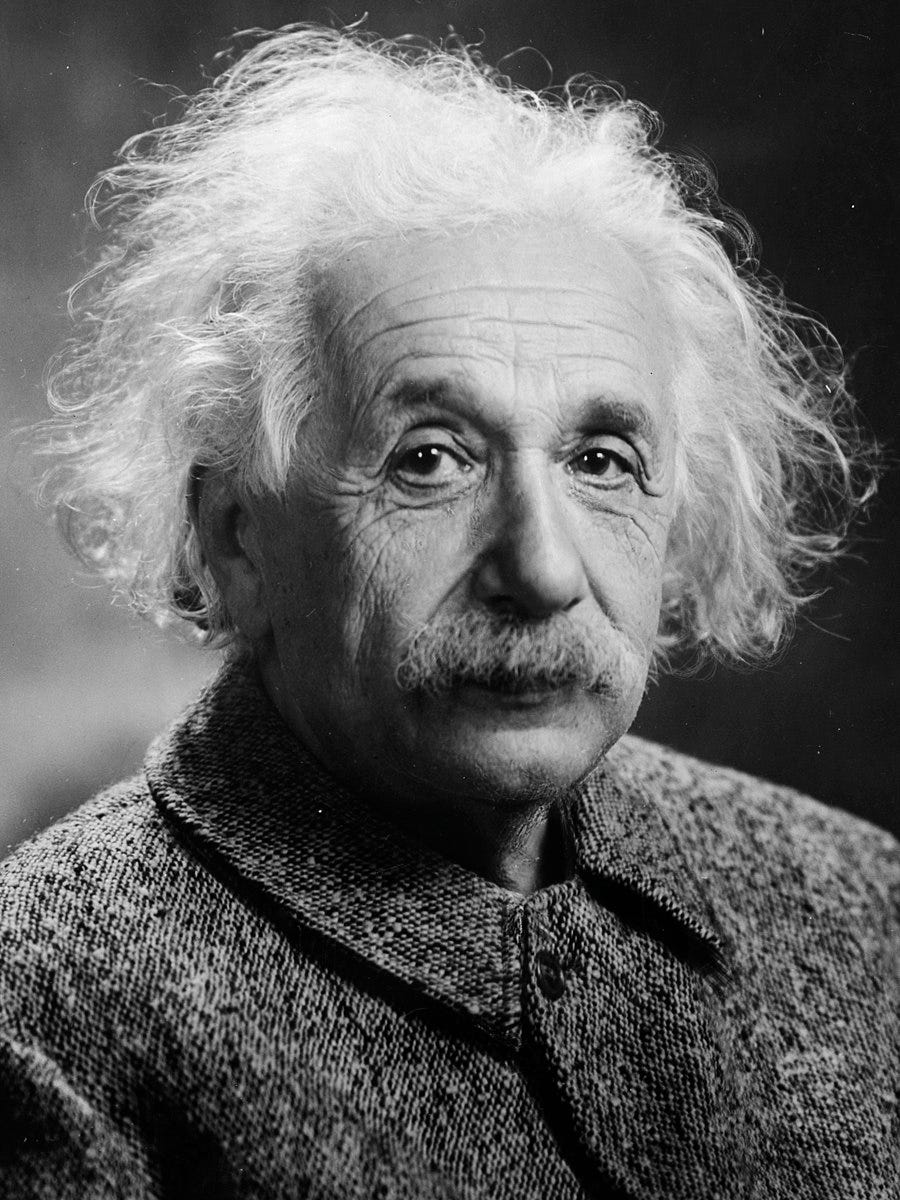

When I let my hair grow, it became wild, frizzy, untamed. D. one morning in the fourth month of this “trial of the hair” took my picture with my hands over my face. I look in that photo like Einstein.

I tolerated this untamed hair for what I hoped would come. I despaired but still I hoped. I tried gels and conditioners but nothing worked. I looked like the wild woman of Borneo. I grew up during the age of big rollers and carry-on hood hair driers. What did I know about this hair?

What did I know of the meaning of this hair rebellion?

I got off a plane to visit my daughter and her boyfriend, students in graduate school at the University of Chicago, and met my daughter’s alarm and unflinching honesty. She pulls no punches: “Your hair looks awful! What are you doing?” And then, her solution in the form of a rhetorical question: “Haven’t you ever heard of a curling iron?”

The French Fry Cutter salesman raises his voice on the commercial in my head: “But wait, there’s more.”

She sat me down on the toilet seat in her tiny bathroom in her minuscule Hyde Park apartment and strand by strand straightened my hair, tamed the hair follicle, lightened its touch to glimmer and shine.

I’m too old to look like the goddess that Michelle Obama is, but my hair moved the way hers did that night the prince and princess won the throne: it shone, it “swang” the way Michelle “swings.” We all know that she’s not tamed. We know that the night Obama won the election men sat in front of their televisions mesmerized by her narrow dress, her delicate hands, her flat stomach and the curve of her hips and all of that started at the top of her head with that 'do.

She “swang” and so did I that night in Chicago. I tossed my hair that, once it had met the curling iron, now lay down in a silver sheen, curled under at the edge of my chin.

I was reborn.

In 1931, the year my mother was nineteen years old, a documentary entitled The Wild Women of Borneo hit the screen. It was black and white, made in the UK. Politically incorrect in more ways than I can describe: I find this attempt at definition of the source of the phrase, “[T]his comes from the Victorian circus habit of calling their black show people ‘wild’ and often attributing their origin to ‘Borneo.’ They were often displayed wearing only a loin cloth, or similar tropical coverings, wielding a spear, or similar. The crowds were attracted with the call: ‘Roll up, roll up, see the wild man of Borneo.’ The ‘wild man of Borneo’ was well established as a concept in the UK before WW2, and possibly earlier. The ‘woman’ version is merely an extension.”

The New York Times tells me about the film, comment attributed to Hal Erickson:

“To say the least, the title of this 68-minute documentary is misleading. For one thing, we don’t see any women until the last few minutes. For another, most of the film was shot in Mexico, which was not then nor is not now anywhere near Borneo. Only after the narrator comments on the natural beauties of the Island of Guadeloupe does the action shift to Borneo, and even then precious few human beings are seen. By the time the ‘wild women’ show up, they are so obscured by trees and shrubbery that no one can get a decent look.”

When my mother was seventy years old, shortly before her stroke, I was applying her make-up for her birthday. She and I were looking in the mirror at her aged face. She said, “I still see the nineteen-year-old girl.”

She was a natural beauty: long dark thick hair, fair skin, hazel eyes, delicate hands. She was obscured by the shrubbery of age. We could both see her through the trees of time. There was no noise while the nineteen year-old girl slid behind the trees.

There was no noise while my hair grew. There was no noise while my daughter tamed the hair follicle with a curling iron.

There was no noise when the avalanche hit in Chamonix, France.

Hairdo as history - so true. Reading this led to my charting the course of my own life through the permutations undertaken via hair lengths, cuts, styles, etc., starting with waist length braids at the age of six to the present day graying crop thinned out by Hashimoto’s disease.

I can't spell the sound I made when I got to those last lines. A punch-short, closed-lipped satisfaction. I want to restack with quote of them but I don't want to spoil it for people so I won't. Also, yesterday, I got a mohawk.