(HQ) Krystian Zimerman plays Franz Schubert - Impromptu Op. 90 No. 3 in G flat major

PianoLegendaryVideo via YouTube

Come in the middle? Here’re links to ➡️ Chapter One, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7

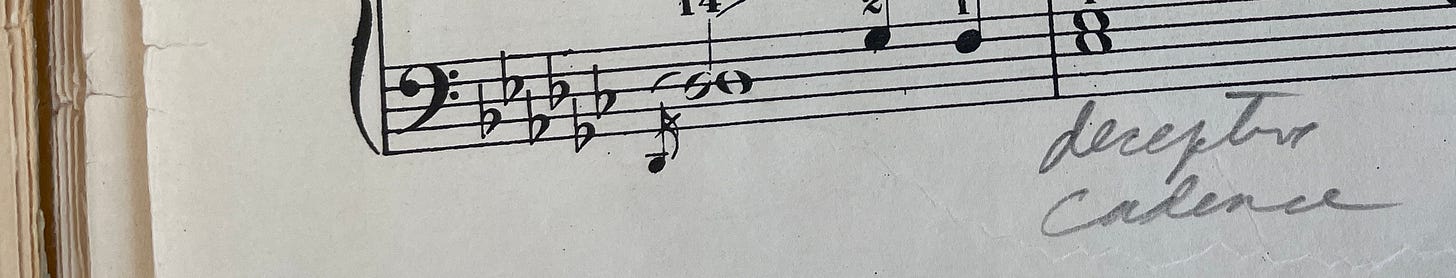

Deceptive Cadence

My husband used to play the console piano we owned only for me—never for anyone else. Before he left me, he bought a 17,000-dollar-black baby grand and placed this Kawai in the front parlor of our old Victorian brownstone before we sold it.

This piano now graces his condo where he lives alone.

I had wanted to buy him a new piano for the last decade: a gift for his birthday. With his perfect pitch and sense of touch, I needed him to play the piano I would buy him but he refused to touch a keyboard in a store.

On the old console that he, with his perfect pitch, refused to get tuned the last years we lived in the house . . .

The houses are all gone under the sea.

. . . on this piano, whose notes must have jarred his ears, he played Shubert’s Opus 90, No. 3 in G Flat. He played it from the old yellow Schirmer’s Library Classics, Four Impromptus book his mother had bought him.

His name in her script in pencil is still on the cover as if he were just another of her many students. A note in ink on the front says Andante Mosso, G with the flat mark in her handwriting and on the table of contents a note that says “prelude” next to the number 3. She was planning to play it for church, prelude to the service. She had written in pencil on page twenty-one of the book whose pages have all come apart: “9 to 10 minutes.” Rubenstein plays this piece in about six and a quarter minutes. She used to tell her son, “If you’re having trouble, slow down.” She took her own advice.

Mosso means literally “motion.” I want to know that he is moved. I won’t be able to hear the piano, but, from having listened—since he has gone—from listening endlessly to Rubenstein on a recording, I know it’s the melody that will move him. He has told me that the melody is exceedingly simple, that any child could play it (I don’t believe this), but this I do know: The melody rings only if all the other keys are struck well and swiftly. It’s these complicated patterns that make you wonder how it’s done, think there’s more going on than two hands could possibly do, when you hear Horowitz or Rubenstein do it—when I have heard him do it. I imagine that when he played it as a boy at the piano that lay against the wall of his childhood parlor, from the kitchen his mother would say, “Now I can hear the melody,” as he tried to get those eighth notes rolling properly, playing up and down the chords, repeatedly, taking the chords and breaking them into their parts, fluidly and separately. Success at this gives the piece its complexity, assures that the rapid notes don’t overwhelm the melody, that both are heard as separate and integrated strands.

I wish for a window near his that I could open and listen: He begins the piece, rolls the eighth notes in his right hand, lightly letting the whole notes ring in his left hand, tries ever so hard to play the whole notes and half notes and quarter notes with that ringing, bell-like tone his mother hoped for.

I once told him a story about dance, an old rabbi’s tale: a story of the deaf who see the sound and join the dance.

We were deaf, could see the sound, but had no dance.

He touched me the way he touched the keys of the piano. A practiced touch to hold my center, to touch my string that lies on my soundboard, to raise my pitch. He wasn’t erect when he touched me. Did he love me? I resisted the letting go though he was always able to get to me, finally, if he played my keys, played them long enough, varied his touch, reassured me that I would come. But I resisted because often he couldn’t enter after. I now know he was aroused.

He couldn’t explain and, cruelly, I accused.

The writer lives in shame of what she’s done and what she tells.

I had to be beneath him for him to come, had to support him with my hand for him to enter. Such an easy thing to do. Such an intimate thing to do.

And yet when he finally left me, I hoped he’d imagine me with another man who, when I lay on my side, would touch me, arousing me in a new way, in a way I hadn’t known possible.

I want him to imagine this man above me, his head flushed, his eyes on me, my hands around his head, my muscles still flexing because I had not come to climax. I could not go fully with any man but my husband.

And then I was sure I would not have him again.

The dancers are all gone under the hill.

He rolls into the G flat major bars, as he deepens his touch in the left hand, the single note melody rising from the strings and the soundboard and then at the same time moving up and down softly on the keys that are the background in the piece. He won’t falter as the piece softens and slows to its first quiet dying fall because he will know through the playing that I have understood that to climax will be the ultimate betrayal of him.

He won’t finish the Schubert: this man with perfect pitch. He will take his hands from the keys, place them in his lap and listen because the music vibrates in our ears when the sound is gone if we will only listen, not move on to something else, but listen, we who have been deaf.

He won’t complete the piece. Each time he comes to the penultimate page, page twenty-seven, there will be his mother’s words on the third staff where the eighth notes are marked crescendo and where below the c whole note that is held for a two-quarter count followed by the d-flat, held for one-quarter, are her words in pencil that refer to the eighth notes in the right hand, deceptive cadence, and his hands will not move forward.

The houses are all gone under the sea.

The dancers are all gone under the hill.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material in chapter 8: T.S. Eliot: Excerpt from "East Coker" in Four Quartets, copyright 1940 by T.S. Eliot and renewed 1968 by Esme Valerie Eliot, reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Love,

Beautiful piece. Love how you weave in the deceptive cadence. The musical metaphors remind me of a line in the Ray King episode of Sex in the City. "Play me like the bass". It's the only way she can connect with him.

Just wow, Mary. So-real-you-can-touch-it musical, instrument-playing metaphor - glorious!

And this: "We were deaf, could see the sound, but had no dance." What a verdict in eleven words!