Come in the middle? Here’re links to ➡️ Chapter One, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, Chapter 9 , Chapter 10, Chapter 11, Chapter 12, Chapter 13, Chapter 14, Chapter 15

Hypersensitive

Stock market crashed. No noise. Economy in dire straits.

Robert Rauschenberg died on May 12, 2008 at the age of eighty-two. That day I walked over to see his work at the Portrait Gallery near my apartment.

I saved the obit., got caught in the web of memory. My own straits.

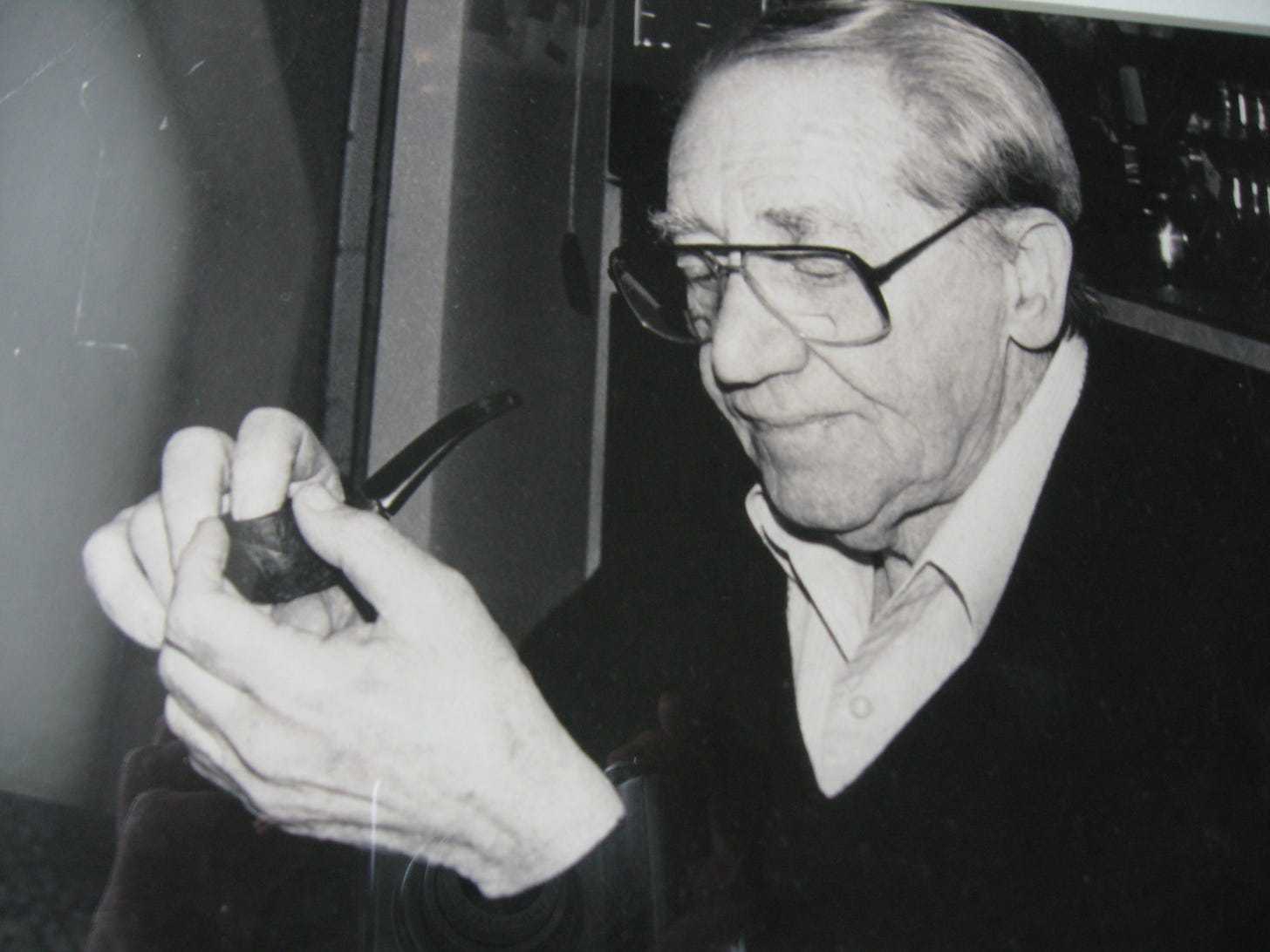

My father’s white shirt, the ribbed, sleeveless undershirt beneath that as a small child I carried with me: “her schmata,” my mother called it. My father’s photo taken by my daughter when she was studying photography in high school, developing her own pictures in Bethesda Chevy Chase High School’s darkroom, hangs on the first wall to my left as I enter my bedroom in the loft where I live and write in downtown D.C. He’s holding his pipe, one finger tamping down the tobacco, the can of Amphora nearby. The photo is black and white and my memory of him, faded to tone. He, a decade gone this June 6, eighty-four and crippled from Parkinson’s disease and a broken hip when he died. He comes to me like his home movies, overexposed, so much light I can barely see him. Rauschenberg-white: my father’s white dress shirt. “I always thought of the white paintings as being not passive but very—well, hypersensitive,” Rauschenberg said. The schmata shirt beneath the dress shirt.

At age 82, my father called me in the middle of the night before he died and in the anguish of aging, asked: “What am I here for?”—a despairing cry that expressed the humility of existence and underscored the imperative of continuing to ask the question even as the darkness moves across us. It is the autobiographical, tautological question that starts and ends where it begins.

My father took my hand, and said, “There’s an inevitability about the present.”

I understood the way I’d understood when my mother, four years after her stroke, decided not to eat when the new year came, when she took my hand and said “Yitgadal v’yitkadash”—the first two words of the mourner’s Kaddish. It was five years later when my father took my hand one hot day in June.

We’d been sitting in the house with the old round Toastmaster fan blowing at our feet, humming the way old memories did inside my head. We’d been talking about the kind of housing called “assisted living.” “Assisted living,” he said. “Funny term. Either you’re living or you’re not, right?”

I didn’t answer.

“I’m on my way down,” my father said. “I know that. This is just a stopover.”

“Stopover from what to what?”

“Don’t get philosophical on me, kid.”

My father’s eyes were brown. I saw them full of light from the sun that angled through the window. I saw the green and yellow—the colors of my mother’s hazel eyes like mine—there inside the brown. I remembered my dream after my mother died. In a haze of yellow light, my mother in a flowered housedress. I couldn’t tell the color of her hair—pure white when she died. But it must be dark—around her face in finger-placed waves, how it was when I could still fit beneath her arm, lean against her curve of breast. Then an empty chair. An elegant, suited man on the sidewalk. My mother, on the stoop of their row house. Her arm raised high in dance position. No one stands inside her hold. She leans to unheard sound. She turns round. A fox-trot circle. My father threads eight-millimeter film through the projector, on the wheel. A home movie. Overexposed. My mother. Like the whiteness of a leafing tree against night sky.

“Why are you crying?” my father said. “This won’t be the last time you see me.”

“It’s what I do. I cry, easily, often.”

“So do I,” he said. “It’s inherited.”

Hypersensitive.

I have looked for him in every man I’ve dated during the last four years—the years of separation. I sensed him one Saturday night in the expert on eastern European economics with big ears like my father’s, knew he might kiss me when he offered his tamarind soda a second time as we ate a late dinner, if you call what we settled on dinner, at Oyamel after seeing a new Claude Lalouch film, yes, that Claude of A Man and a Woman, a movie this sixty-six year-old, tall lanky man had seen at the Circle Theater, a D.C. relic, razed now. I saw it with my father when it first hit theaters, had Netflixed it two weeks before meeting this man.

Was the camera hand-held? as Lelouch circles round the lovers as they meet on the train platform after they’d parted, after she’d said she could not make love because of the memory of her dead husband. Her lover, rebuffed, left her. She took the train. He rethought on the drive back in the Mustang, met her train. Francis Lai’s soundtrack strikes me now as sentimental, but, like a memory, Lai’s rhythm and the humming singers resound, will not be resisted. No rational thought. No editing. No chance to cut the sweet and to the core where I like to be.

When I danced with my husband, I once upon a time hummed. D. has perfect pitch, a curse and a blessing. For me, a curse. For him too I now think: To have heard those off-notes from my throat, the vibration of my vocal chords gone wrong, not tuned. Off pitch. No humming allowed. Not on that chest where I lay my head when we danced. This man says he is working on the question, “Who am I?” while I wait.

T. S. Eliot tells us,

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

That Saturday night at Oyamel, the economics expert offers me the tamarind soda on first pour (I refuse) and then offers again after he’s drunk half. My father and I shared chocolate soda and coddies at the drugstore soda fountain on Dolfield Avenue, three blocks from Grantley Road where I grew up in Baltimore. We’d walk there together, wait for my mother who was getting her hair done at the salon next door.

Lanky man’s tamarind soda doesn’t measure up to his memory when he was in the Peace Corp in Columbia where the beans were refried more times than his strong stomach could bear and where he went into town for a tin of cookies and the soda, ate the whole tin, sloshed back the soda. I taste the second-hand and secondary soda, the hint of spice and tart rind that recalls my mother’s glazed orange peel that my father and I would have at home after the coddies and mustard on saltines.

This man had held my hand on the first date, not again on this Saturday night, not once in the movie or while we walked. That first date, one glass of wine and nothing much to eat at the Tabard Inn (nothing much to eat this night either. Is he cheap? my daughter asked.) Did I care?

Later I did care. My daughter began referring to him as “Cheapskate” after I took him to dinner at Tosca and it seemed only fair I should pay. I ordered a bottle of wine. He didn’t object. He ordered the salad, an appetizer, the pasta, the dessert. The thin man did eat when he was not paying the check.

Thank goodness I wasn’t dating him as the economic crisis deepened. Would he dare even to go out?

But his quiet, his calm like the sense of the sea receding with the tide; his angles like my father’s, a Giacometti sculpture in shadow at the edge of sand in fading light.

That first date we’d descended the escalator at Dupont Circle, knowing that we would go down together to separate at the platform. He’d said, “Ah, so I get to hold your hand for a bit more?” as we descended the long arc down. The slight lift in his voice as if it were a question though we were palm on palm all the way down as he recalled a scene from the movie Risky Business: the departing train through the narrowing perspective of track on track, a camera’s eye in his words, the sound of sex in his voice: Rebecca Mornay and Tom Cruise making love on the train, politely unspoken between us.

He had not touched me since that first palm-on-palm moment. The afternoon he’d called with his “research,” as he called it from the website Rotten Tomatoes, reviews of movies playing at the E Street Theater, the first on his list, Roman De Gare, “Claude Lalouch,” he said. “That Claude,” I said and named that movie we’d both seen in 1967. “Ah, yes,” he said. I didn’t know Lalouch was still around. I cast my net back to the year I turned twenty-one. “Let alone alive,” I said. And so we chose the third-date movie.

After Oyamel, two tapas (hearts of palm salad and two scallops, the soda and a licorice tea), he walks me to my loft where I fob the glass front doors open.

“Would you like to walk me up?”

“I could do that.”

We ride in the elevator, apart, then a short walk to my door. I turn the key. The bolt slides open with the click of certainty. I turn my back to the door. He is 6'2''. I am 5'4''. He bends, a curve of slender grace as he slides his hand behind my head and he kisses me. I kiss him and then again. He holds me against his chest, his arm around my back.“You are a sweet man,” I say into the knit of his cashmere sweater, my childhood cheek against my father’s heart, the white shirt, the soft-ribbed undershirt beneath.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material in chapter 16: T.S. Eliot: Excerpt from "Little Gidding" in Four Quartets, copyright 1942 by T.S. Eliot and renewed 1970 by Esme Valerie Eliot, reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Publishing Company.

Coming next: Chapter 17, “Cinderella” Table of Contents

Love,

What a gorgeous, evocative picture of the power of memory. The color, feel, smell, sound that is forever there, maybe hiding quietly, maybe rushing forth in the moment. Always presenting the unanswerable question. Brilliant.

Mary, I'm in absolute bits. This goosepimpling chapter - this on-the-button, almost relentless staccato delivery of your story - has such colour, such depth, such brutal humanity.

AWESOME. And extraordinary. 🙌