Come in the middle? Here’re links to ➡️ Chapter One, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, Chapter 9 , Chapter 10, Chapter 11, Chapter 12, Chapter 13, Chapter 14 , Chapter 15 , Chapter 16, Chapter 17, Chapter 18, Chapter 19

I’m Cooked

The chase begins again in earnest, on my part anyway, with another widower, an aerospace engineer, who some eight months before lost his wife to lung cancer (quick and pernicious and I don’t think she smoked).

I believe in rescue. I mistyped that at first and wrote rescure, saw the word cure inside and wondered how crazy or crazed I am. I know we must rescue ourselves. You don’t have to tell me that. But when our goose is cooked, don’t we all want the guy on the white horse—even if the horse turns out to be stationary and turning on a merry-go-round? Where you might think I am at this point.

And I’m with you.

So I read the paper: “Almost exactly two years after it embarked on the biggest financial rescue in American history, the Federal Reserve acknowledged that the economy,” according to The New York Times, “was pulling out of its downward spiral and announced a step back toward normal policy.”

I believe my downward spiral is ending. After all, it is August, the month the shrinks escape, gardens overgrow, and children turn off the TV to go buy school supplies.

I meet the second widower one Sunday morning on the Internet—let’s call him m.r.s. (his initials and he, as you will see, is widowed but still married), profiled in Forbes, owns his company consults with the Pentagon but he is not a Republican, thank god, (yes, I googled him)—and we agree to meet for an early dinner at Matchbox, great pizza, near my condo. He flirts with me through messaging: “You are a beautiful woman and write with both a comic touch and a real sense of romance/passion. It brings out the foolishness in us men. I like the Robert Browning line, ‘Grow old with me, the best is yet to be.’ ”

Here is what he is referring to (Oh sure, my photo from the year D. left me—so I don’t look that good now anyway)—and my Internet dating profile: see what you think:

“I’m a fiction writer. I’ve returned from a visiting-writer gig at a major university in the Midwest. I am separated, have been for almost four years, live alone, own my own condo. I would like to talk with an intelligent man interested in the arts and who actually likes the part of my profile that begins: I’d give most anything to see Érik Bédard pitch against the Yankees. But then, of course that fact fits with these and, if you see what I mean, you may like to talk to me: I read literary fiction and poetry (Nabokov, Joyce, Wolfe, Roth, Bellow, Kunitz, Bishop, Lawrence and especially Auden); love the movies, anything and everything, think a great actor gives us a backstage pass to his soul; loved Wild Strawberries, Match Point, and The Thomas Crown Affair (the second version! —go figure? But Steve was great in the first one.)”

The profile, by the way or not so by-the-way, I hide after m.r.s.

I can’t do this anymore and here’s why:

m.r.s. hit me, the sight of him, like a ton of bricks. I was immediately smitten and then he spoke: He speaks of literature and Mother Teresa, he plays bridge, he had sex with his wife every day for thirty-five years, until she got sick, he thinks I’m beautiful, he holds my hand when we cross the street, and I am a goner. He’s been widowed for only six months. And, to this question that he actually asks on the first date, “Do you believe in beshert?”—Meant-to-be would be the loose translation of the Yiddish—I answer, “I do.”

Remember in Four Weddings and a Funeral when Andie McDowell advises Hugh Grant on getting married? “It’s pretty easy really,” she says in the church at his wedding to Duckface. “Whenever someone asks you a question, answer ‘I do.’ ”

I think a second chance (Okay call it a third if you’re nitpicking about my two marriages) fortuitously walked into my life and a door I thought was forever closed opened.

We neck impetuously on my couch and move to the bedroom with his pleadings. He says we must not make love—though he does want to—“but can’t we take off some of our clothes and lie down together? You can do this,” he says. I answer, “I can, but I’m old.” He says, “You have the shape of an hourglass.” Not true: I look like a small bosc pear. But it was the perfect response, time and shape in metaphor. He is a short (D. is so tall), gorgeous man—he and I are exactly the same age (D. is almost four years younger—perhaps that explains the wreckage?). m.r.s. is an Aries and I am a Pisces. Believe it or not, this aerospace engineer ends up telling me he was born on the cusp of Pisces (the twelfth and final sign of the Zodiac) and that he is ruled by Mars and Neptune. So, he says, we are a Neptune/Mars combination, on the cusp of rebirth, associated with the beginning of human life.

So, I cook the Thomas Keller chicken for him.

At that dinner I serve the chicken, the roasted potatoes, carrots and shallots on my farm dishes, the naïf pattern by Villeroy and Boch.

m.r.s. tells me he bought the full set for his wife when he was in Luxembourg where they are made. He is speechless before his dinner plate.

I am unglued. Like a school girl: Remember promise in giant red doors you saw while your knees shook at the edge of the playground with book bag and lunch pail, cold from the thermos of milk? The sound of the future in the creak of the bindings of black and white speckled notebooks? How hope smelled in the wood of sharp yellow pencils? Remember how long red margins ruled down the side of lined paper you titled “My Summer Vacation” and you learned at hard desks how to write—in narrow white spaces—of weather, and clothes, and long days at the beach instead of skies bursting color like peaches and plums or birds’ feet on sand like the sweetness of time?

He calls the next day after the roasted chicken to say he is overwhelmed with guilt even though his wife is dead. He tells me he “feels badly.” That he is attracted to me but that that is the problem. He tells me he did not mean to mislead. He tells me this before he explains the Gaussian concept in answer to a question I have about a scientific passage I am writing in my novel-to-come Who by Fire.

I am hearing the message loud and clear: In short, he is not ready.

I am devastated, again. I write him:

“Dear m.,

“You may indeed feel bad that, for example, you were not able to sleep over with someone you liked for complicated reasons that you could barely even explain (note the proper use of the adverb ‘barely’)–but you do need the adjective to describe this state of mind. However, if you were not able to touch her, you would appropriately say that you have lost your sense of touch; for example, I could not touch her because I feel badly; I can barely tell her skin from her teeth, without telling her of course that you wished to escape by the skin of your teeth (refer to Thorton Wilder for more on this last phrase.)

“The reason for all this is that the verb feel when used to describe one’s feelings does not take an adverb. That is because it is what as known as a ‘linking verb,’ much like the verb to be, and it takes what in grammar is known as a ‘subject complement adjective.’ But the verb, though it works like the verb to be, cannot be replaced with the verb to be.

“Thus, the confusion among educated folk. A person who feels bad is very rarely, though could be, bad. As in the phrase: I am bad. Something none of us wants to be except in the bedroom, of course, where consenting adults may be as bad as they both think appropriate.

“I write this note to you because I would feel bad if I had misled you as to the proper usage of a word to describe one’s feelings.

“Grammatically yours,

I call D. and tell him I think we truly need not see each other until after the agreement is signed. I tell him I’m an all or nothin' girl and I can’t bear what’s happened. I have to find a way to live with what happened. I have to find a way to move on.

I do believe my heart is broken and that I’m a fool. I call my daughter Sarah and tell her about m.r.s. She’s been burned by both D. and m., the first widower, the psychiatrist, and now sees me as foolish, impulsive, inexplicably romantic and has begun not to answer my phone calls.

She writes an e-mail in the morning instead of calling me back: “I heard the phone ring downstairs when I was asleep last night. This morning I saw it was you. Is everything okay? Sorry I didn’t pick up. By the time I was awake enough to know the phone was ringing it had stopped.”

“Did you see this article?” She includes a link to a site in Paris from our favorite newspaper The New York Times where now I am reading about the economic recovery that is not quite here—and ain’t that an understatement, as I watch Obama try to wiggle us out of the crash.

She says, “I think we should take cooking classes in Paris together. Wouldn’t that be fun?” She and her husband Ryan and Lila, my grandchild, are going in September for six months: Sarah will have no time for cooking classes between the research for her next book and Lila. But she knows I need to recover and that I’ve planned to rent an apartment in Marais. I hope to write in a garret (another dream?) while the world goes south.

I find this at WIRED where Felix Salmon said,

“A year ago, it was hardly unthinkable that a math wizard like David X. Li might someday earn a Nobel Prize. After all, financial economists—even Wall Street quants—have received the Nobel in economics before, and Li’s work on measuring risk has had more impact, more quickly, than previous Nobel Prize-winning contributions to the field . . . For five years, Li’s formula, known as a Gaussian copula function, looked like an unambiguously positive breakthrough, a piece of financial technology that allowed hugely complex risks to be modeled with more ease and accuracy than ever before. With his brilliant spark of mathematical legerdemain, Li made it possible for traders to sell vast quantities of new securities, expanding financial markets to unimaginable levels . . . Li’s Gaussian copula formula will go down in history as instrumental in causing the unfathomable losses that brought the world financial system to its knees.

“How could one formula pack such a devastating punch? The answer lies in the bond market, the multi-trillion-dollar system that allows pension funds, insurance companies, and hedge funds to lend trillions of dollars to companies, countries, and home buyers.

“A bond, of course, is just an IOU, a promise to pay back money with interest by certain dates . . .

“Bond investors are very comfortable with the concept of probability.”

I ask you: What is the probability that my goose is cooked?

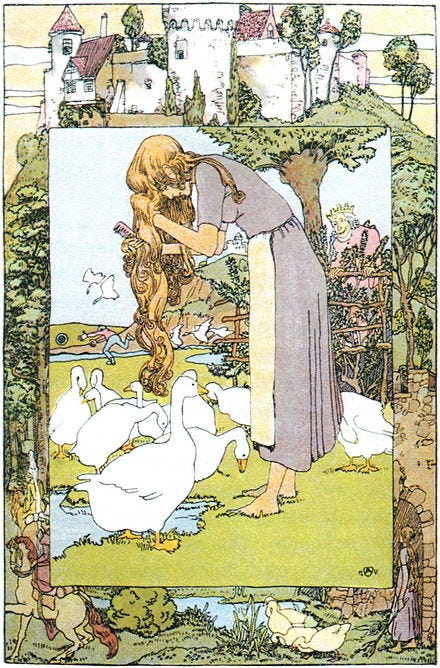

In the Grimm Fairy Tale “The Goose-Girl,” a beautiful princess is betrayed and, instead of marrying her prince, must tend the geese while her talking horse Falada tries to save her even after his murder, after his head has been pinned to the wall. The princess is now the goose girl who, after driving the geese into the country, unravels her plaits of long golden hair that shone with radiance.

But Falada can save her because his head, nailed to the wall can reply when the goose-girl says, Ah Falada, hanging there!

Falada says and the prince’s father learns of his reply: Alas, young queen how ill you fare! If this your mother knew, her heart would break in two.

Could it be that D. will ride a white horse? Or is he on the merry-go-round with me?

The real q.: How would Carl Friedrich Gauss measure the probabilities?

Coming next: Chapter 21, “Double Doors” Table of Contents

What do you think about “the good, the bad, the foolish” of me so far? Your comments mean everything …

Love,

First, the mental connections you make!

Second, My God, Mary -- that letter! I am sure you rendered m.r.s. speechless. The emotional instruments you wielded. Without doubt, he regretted his unpreparedness.

Oh Mary…these men. They deserve every bit of your schooling!