Come in the middle? Here’re links to ➡️ Chapter One, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, Chapter 9 , Chapter 10, Chapter 11, Chapter 12, Chapter 13, Chapter 14 , Chapter 15 , Chapter 16, Chapter 17, Chapter 18, Chapter 19, Chapter 20, Chapter 21, Chapter 22, Chapter 23, Chapter 24, Chapter 25 , Chapter 26, Chapter 27, Chapter 28, Chapter 29, Chapter 30, Chapter 31, Chapter 32, Chapter 33

Hat Trick

After seeing the movie Paris with D., we go to sit on his balcony and drink good red wine I cannot name though I would like to say it was French, suspect it was Spanish—we are a little drunk. His apartment is near the Verizon Center and the Capitals are playing. We are so close we can hear the blare of horns. When he checks the scores, we learn that the Caps are beating Toronto three-zip.

D. thinks that Alexander Ovechkin may have a “hat trick”: three goals in one game. But it turns out that Ovechkin has two goals and one assist. Not bad. Final score Caps 6, Maple Leafs 4. I read the next day Washington AP: “By the time the game was 77 seconds old, Alex Ovechkin scored the first time his stick touched the puck, earning ‘MVP!’ chants from all those red-clad fans.” Surely he will get the hat trick again the way he did against the Pittsburgh Penguins.

I am stuck on the hat trick. For me the movie Paris is Cédric Klapisch’s and his favorite male lead Romain Duris’s hat trick: L'Auberge Espagnole (filmed in Spain) and Russian Dolls (Paris, London, St. Petersburg) and now a window on Paris from a non-rom-com view that includes Romain Duris’s view of the city from a taxi. In that one scene we see rom-com Paris: the Tour Eiffel, the golden statue, a rom-com collage but not as I’ve ever seen anything in that much-filmed city filmed—not as I perceive the city by then. For Klapisch has closed with the hat trick.

What we have seen by then is the refrigerated fruit and vegetable outlet while in most Parisian movies we see romanced markets in the street. We see them here too but with the gloss from the grit of living. We see refrigerated meat lockers. We see flowers pushed on an industrial cart by a strong young working-class woman. We see academic Paris. We see dancing, dream-like Paris (Romain Duris, slim beauty in red) and tiny apartments that bespeak living in the spaces of the heart—not the spaces of Architectural Digest.

No villains and no heroes. Humanity on full compassionate show culminating in the simple exchange that brought me to tears: “Merci” and “merci aussi,” built on the relationship of the characters played by Romain Duris and Juliette Binoche who speak these words.

When we leave the theater, D. says to me, as he makes a note to himself on his Blackberry, “It was Bach’s Minuet in G Minor in the score.” — a childhood memory from when he was learning to play the piano. Here is Lang Lang playing it:

I’m struck that he hears what I do not hear, that he brings music to me.

He seduced me with his piano, the one with the crack in its sounding board, the one he sold when he married me. He had little furniture when I met him, had placed his baby grand as the centerpiece of his living area.

When we first knew each other, he called me and told me he had a gift for me and I should come over from my place, a tiny house in Garrett Park estates—meaning that all the old big Victorians were in Garrett Park and that I lived in the estate, the extensive land where the poor live near the rich. We used to call his apartment up on Pooks Hill California because the kids and I went there to swim in his pool, to sit on his balcony, to stand in the shiny-like-marble glistening lobby—a world apart. I came that day and he played Beethoven’s “Pathétique” and then without words, with instead the simple silence that follows the end of a piece, the laying of his hands in his lap, he looked at me. And I wept. I’d wept from the first melodic chord.

This was the last time he played the piano for me—twenty-eight years ago. When we lived together, I often heard him work on Schubert’s Impromptu in G Flat but he’s never played it for me all the way through.

The barren period. Music in silence. When I heard him play, I’d be upstairs in our large Victorian house in Adams Morgan—we’d come such a long way but not come through.

All the silence would seem to me to be gone when I heard him play.

A piano teacher once told me the story about the man who was lucky enough the night before a concert to get a hotel room next to Rubenstein, or was it Horowitz? She’d forgotten which. The name did not matter. What mattered was that the man heard through the wall the same phrase played over and over and over, like a needle stuck on a scratch in a record.

D. and I are stuck like that.

Before all the loss, when I watched him play the day he seduced me, I saw the muscles in his shoulders, his forearms, the angle of his back. The movement of his brow, the corner of his mouth, the line beside his eye. I watched his body move through the piece. He leaned into the bass. The melody rang from the keys, shifted in tone, in softness and loudness with his touch. His back curved into the music, his brow softened, his shoulders rose and fell with the thematic repetition. His neck bent and relaxed.

What he does not know is that when I heard the Schubert in G, as I lay in the bed where I waited for him, where I often fell asleep before he came to bed, I didn’t hear the missed notes, the imperfect phrasing that he explained as the reasons he could not play for me or anyone else.

I thought I heard his heart pulse, but knew it was my own.

I am stuck on the hat trick: Will he pull the Schubert in G out of his? Will I pull Paris out of mine? Is there another trick that awaits?

When Alex Ovechkin pulls the trick, the ice will be full of hats. This tradition owes its history to cricket when a bowler knocked off three wickets and was awarded with a hat.

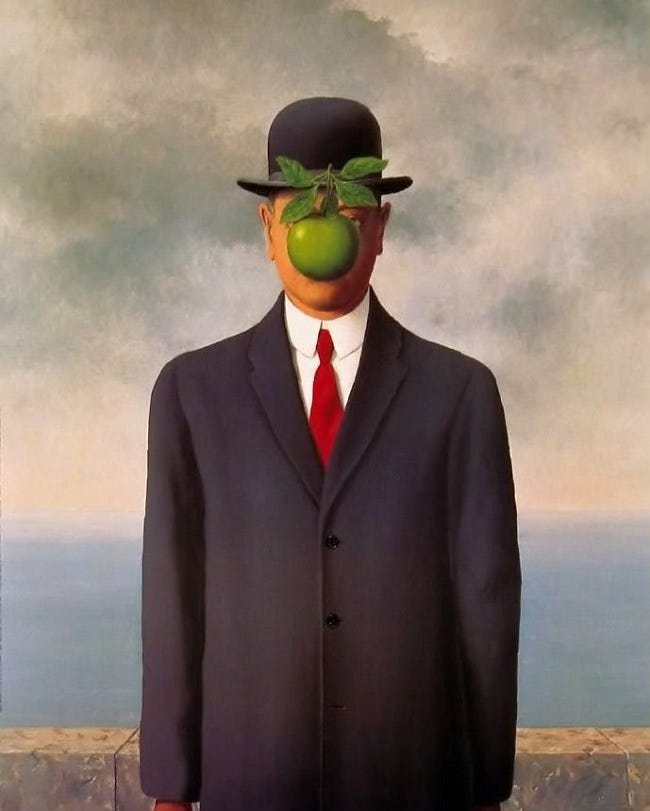

I am reminded of my favorite rom-com The Thomas Crown Affair—not the first one with Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, but the second with Pierce Brosnan and Rene Russo. Tommy, played by Brosnan, has three tricks to pull. In the last, Tommy hides by wearing a bowler hat and filling the museum with men in bowler hats, an allusion to the painting Son of Man by René Magritte: a man who wears a suit and a bowler hat with an apple on his face.

When we truly see, we see what’s been hidden: the hat trick.

Coming next: Chapter 35: “Bed Trick” Table of Contents

Love,

Wonderful. This piece left me dazzled by the range of references and engrossed in the wonderful details. The repeated mention of a hat-trick kept making me think of a bed-trick in a Shakespeare comedy, which somehow seemed to make sense. I understood D here a lot more, too. Someone who can't play a piece of music because it's not perfect is someone who quibbles over how life and words and actions all align.

The descriptions of Paris made me think of Walter Benjamin on Baudelaire: "For the first time, with Baudelaire, Paris becomes the subject of lyric poetry. This poetry is no hymn to the homeland; rather, the gaze of the allegorist, as it falls on the city, is the gaze of the alienated man. It is the gaze of the flaneur, whose way of life still conceals behind a mitigating nimbus the coming desolation of the big-city dweller.” Something like Benjamin's wonderful "mitigating nimbus" seems to be at work here.

"This tradition owes its history to cricket when a bowler knocked off three wickets and was awarded with a hat."

Part of my education for the day.

The melancholy is unbearable.