Come in the middle? Here’re links to ➡️ Chapter One, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, Chapter 9 , Chapter 10, Chapter 11, Chapter 12, Chapter 13, Chapter 14 , Chapter 15 , Chapter 16, Chapter 17, Chapter 18, Chapter 19, Chapter 20, Chapter 21, Chapter 22, Chapter 23, Chapter 24, Chapter 25 , Chapter 26, Chapter 27, Chapter 28, Chapter 29, Chapter 30, Chapter 31, Chapter 32, Chapter 33, Chapter 34, Chapter 35

Run and See

I’m stuck on romantic comedies: good ones, middling ones, the watch-me-over-and-over again ones: Runaway Bride is like a children’s book for me. Remember when you were a kid and your mother or father read you a story before you went to bed and you said, “Read it again”? It’s that way for me with Runaway Bride.

It was that way for me with The Runaway Bunny, the Margaret Wise Brown classic—but not as you’d expect: Yes, my children loved the book but I actually don’t remember it from my own childhood.

I recall it from reading it to them, to Ben and to Sarah, and wanting to read it again and again—more now than when my children were small and needed to be read to, needed to be tucked in.

I’ve watched Runaway Bride more times than I would like to admit—as if its formula will serve up the answer to my dilemma, the dilemma of the woman who’s been dumped—or so she thought. It’s not as if the evidence wasn’t real: D. did leave, the house is sold. But these are the trappings of loss. Something at the center of this seeming disaster awaits discovery.

So, I turn to Runaway Bride: The bride who runs away in the Garry Marshall film is played by Julia Roberts. This bride runs at successive weddings. She runs like the runaway bunny to find herself and still be safe. Julia’s character runs from the hippie rock singer, the broken-hearted-soon-to-be priest, the entomologist, the football coach and even from Richard Gere, playing a journalist-wanna-be novelist, who does truly get her, who knows that she ate her eggs the same way every man she’s been engaged to ate his. It’s a tired metaphor that in the rom-com works as we watch her lay out the eggs prepared as she once ate them in each former relationship: scrambled, poached, fried, egg-whites-only omelet—and finally Benedict—not Arnold—her final choice when she’s ready to give up her running shoes and wed.

Benedict Arnold—the general who changed sides during the Revolutionary War, who joined the British when the colonies were seeking their freedom—has nothing to do with Julia’s egg choice and everything to do with why we run away: The treason for which his name has become synonymous is inextricably tied to the struggle to be independent. I could argue that I was betrayed but perhaps identity was at stake: both D.’s and mine.

I’m no longer sure of who needed more to run: D. or me.

I often dream of D. and the sea: At the beach. I want so to go to the beach. But a man has come to my house by the sea to say that someone is going to be killed. Someone is watching the house in a car. I must lie down below the windows so I’m not seen. I’ve asked that D. come across the beach to meet me, but I cannot go out. I’m afraid to go out. He’s on the beach and though it’s warm out he is wearing his cashmere watch cap and his coat. The water is sliding up on the beach, clear and blue and covered with foam. I don’t go out at first because I know that someone is going to be killed. But there D. stands alone, waiting. I go onto the beach but he is gone. Another man tries to give me a package. I won’t take the small package because I know what is inside: Something wrapped in sausage skin, like a disembodied penis. I refuse. I walk on the sand, put my feet in the water.

I wake, thinking it is morning. But it’s only 2 a.m. and I’m tired. I think it is morning because the street lights, or is it the moon? cast a glow inside my bedroom.

Like most dreams this one makes no sense and total sense. Its Freudian implications seem clear: disembodied penis and all. But I’m drawn to the light cast by the moon with the love of the sea in my heart.

I lie alone in bed only to discover that the someone who is going to be killed is me.

Like the runaway bride, I must choose my own eggs: I must kill the self that could not be seen.

My daughter had a boyfriend who gave her The Runaway Bunny after they’d parted: I recall this suitor as a smothering blanket. Run, run, I thought, when she finally ended the affair. His gift copy of the book sits inappropriately on my bookshelf with his inscription (not mine to reveal) on the facing page. His contact info below his words lies like an unfulfilled wish. My daughter Sarah, self intact, is married now and in Paris—the one that’s on the map.

In the rom-com, Paris is not on any map.

And I’m soon to runaway there: the trip is planned. Which will it be? Paris on the map or Paris in the rom-com?

As we now know, I’m obsessed with rom-coms because in the good ones wisdom and fantasy meet. Watch Runaway Bride and wait for the speech that Richard Gere’s character states and that Julia’s later repeats. It goes like this: I guarantee that we will have tough times. I guarantee that at some point one or both of us will want to get out. But I also guarantee that if I don’t ask you to be mine, I’ll regret it for the rest of my life.

I’m in the tough times and the gettin' out time. What to do?

Watch another rom-com.

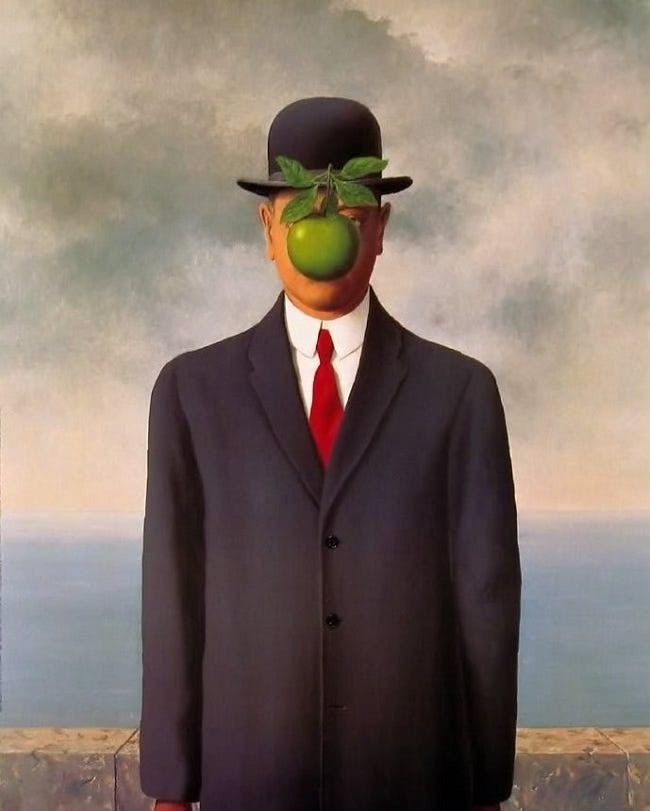

In The Thomas Crown Affair that I also watch over and over again, the painting by René Magritte Son of Man plays a key role as its image of a man who wears a suit and a bowler hat with an apple on his face appears again and again. Tommy, played by Pierce Brosnan, is that enigmatic man who will soon be known: life as he knew it erased but self fully intact.

In a book I love by John Berger entitled About Looking, Berger quotes Magritte on his view of paintings as “material signs of the freedom of thought . . . Life, the Universe, the Void, have no value for thought when it is truly free. The only thing that has value for it is Meaning that is the moral concept of the Impossible.” Berger comments, “To conceive of the impossible is difficult. Magritte knew this.” And later in the essay Berger adds, “If a painting by Magritte confirms one’s lived experience to date, it has by his standards, failed; if it temporarily destroys that experience, it has succeeded. (This destruction is the only fearful thing in his art.)”

I have feared the destruction of my perceived experience, of my illusory self. But I now know that in destruction lies discovery.

So, I will run to Paris, but I will run with this knowledge: That I am both the runaway bunny and the runaway bride.

Let the rom-com roll, for my role in it emerges the way the apple in Magritte’s painting cancels out the face, and in its absence, holds before me the chance to see.

Grateful acknowledgement for excerpt from About Looking by John Berger, deemed “fair use” by Random House.

Coming next: Chapter 37: “Transom” Table of Contents

Love,

How interesting, Mary. Perhaps I've commented on this before, but I am not a rom-com person, being more of the psychological thriller bent. I wonder if this was always so, if a film like "Jacob's Ladder," seems to lie closer to the truth to me, hence my preference? I also remember seeing "Love, Actually" as a matinee with a girlfriend I'd been living with for a year, how it clarified things for me about us in exactly the opposite way that it did for her, how we came home and she asked if I'd ever thought about marriage, and it made me cry, and then she knew that we were done. What a cruel shock that must have been for her. Maybe my view of rom-coms as fundamentally dishonest stems from that.

Love it.

Fond memories of The Runaway Bunny, Goodnight Moon was another favourite.

Stuck-in a good way with these: discovery after the destruction and how in absence , there's a chance to see ... thought-provoking piece.